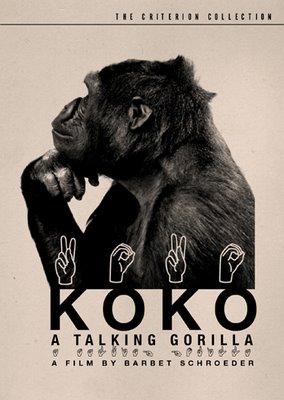

My kids are six and a half months old now, and they are increasingly enjoying their ability to make sounds with their vocal cords. I am also told that now might be a good time to get them started on “baby sign language”. So it seemed like as good a time as any to check out Barbet Schroeder’s Koko: A Talking Gorilla (1978), a documentary recently released on DVD by Criterion.

My kids are six and a half months old now, and they are increasingly enjoying their ability to make sounds with their vocal cords. I am also told that now might be a good time to get them started on “baby sign language”. So it seemed like as good a time as any to check out Barbet Schroeder’s Koko: A Talking Gorilla (1978), a documentary recently released on DVD by Criterion.

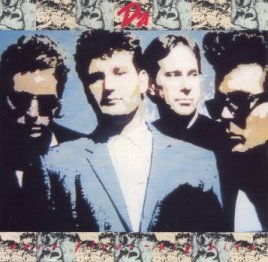

The first time I ever heard of Koko was nearly two decades ago, when Daniel Amos, one of my favorite bands ever — then going by the abbreviated moniker Da — released Darn Floor Big Bite (1987), possibly their best album ever. The album’s title was adapted from Koko’s sign-language description of an earthquake, and the album as a whole is all about the nature of communication and the inability of language to fully grasp the things it describes.

As Da frontmman Terry Scott Taylor sings in ‘Strange Animals’, we “move around in a big make believe” because we rely on words to communicate — but the things and people that we describe have realities of their own, the depths of which our words can never quite cover. A gorilla calls an earthquake a “darn floor big bite”, and a human being calls God “a roaring lion and a consuming fire”. Doesn’t quite tell the whole story, does it? And yet these phrases do point in the right direction.

As Da frontmman Terry Scott Taylor sings in ‘Strange Animals’, we “move around in a big make believe” because we rely on words to communicate — but the things and people that we describe have realities of their own, the depths of which our words can never quite cover. A gorilla calls an earthquake a “darn floor big bite”, and a human being calls God “a roaring lion and a consuming fire”. Doesn’t quite tell the whole story, does it? And yet these phrases do point in the right direction.

Taylor may have made at least one more reference to Koko in his music after that, in a track called ‘CoCo the Talking Guitar’ on the Swirling Eddies album Outdoor Elvis (1989) — but the similarity in name may be unintentional. Still, given that the whole point of teaching Koko sign language was to prove that apes are people too, I find it interesting that the one time her name (or something like it) is mentioned in one of Taylor’s recordings (and not just in the liner notes), it is attached to an object that has incredible communicative power — but only when someone else plays it.

Schroeder’s film, for the most part, follows Koko around as she interacts with other animals and the humans who work with them, especially a woman by the name of Penny Patterson. Koko’s behaviour is quite remarkable, but there is some debate as to whether the gorilla should be considered a “person” like the rest of us. There is also some debate as to whether the gorilla has been unnaturally “humanized” by being taken out of its habitat and integrated into human society. At one point, the narrator asks:

In their natural habitat, gorillas live according to strict hierarchical rules. Each must obey his superior in the group strucutre. Penny would be in danger if she didn’t assert, when necessary, her dominant role. Education implies dominance. How could Penny avoid transmitting her own values? Will Koko begin the first white American Protestant gorilla?

In another scene, the head of a zoo that claimed to own Koko as its property — though perhaps not in those words — remarks:

A gorilla, you know, is not a person. And I think maybe Koko was made to be a person. And I’m not sure that that’s a– As I say, that is an unnatural thing, certainly. For a gorilla, the word “good” and “bad” has no meaning whatsoever, no– And of course for us it doesn’t either, unless we’re taught by our parents. And, you know, that’s not being a gorilla. A gorilla is not good or bad, either way; no matter what it does, it’s not good or bad, because it’s just a gorilla and you can’t impose our value judgments on a gorilla.

This raises all sorts of fun questions. If the words “good” and “bad” have no meaning for us unless they are taught to us by our parents, then where did our parents get these words from? Penny sometimes chastises Koko and uses the word “bad” to critique her behaviour — but does that word mean for Koko what it means for us? Is Penny functioning as Koko’s “parent” when she does this?

If gorillas were given the rights of a person, would they not also have to have certain responsibilities, too? Or would there be different classes of “person”? The narrator may hint at something like this when he asks, later on, “Why must human behaviour be our only standard?” But then, if we create different classes of “person” between humans and other animals, what would stop us from creating different classes of “person” within humanity?

There is a scene early on where the camera sits in a car going to the institute where Koko lives, and we pass numerous restaurants and gas stations and other corporate buildings. The narrator remarks that the names of the streets point to the fact that there used to be forests here — forests that have been all but eliminated, except for two tall redwood trees that we happen to pass.

Presumably, this moment was added to the film to indicate how we humans have ruined nature by believing ourselves to be above it, the same way we believe ourselves to be above the other animals. But the paved desolation of those roads — the very modern sensibility it reflects — could just as easily reflect the tendency of science to flatten things out by dismissing their intrinsic worth. Human beings become nothing but tissue, our minds become nothing but complexes of electro-chemical reactions, morality becomes nothing but social conditioning — that sort of thing.

Am I arguing, against the opinions of certain people in the film, that human beings are above nature, in some way? Yeah, I am. But I certainly don’t believe that we are apart from nature — and so long as we human beings eat food and leave behind our various waste products, I don’t see how anyone could believe that.

The scientists in this film occasionally speak against the traditional religious belief in the unique worth of human beings, but I think that’s an unnecessary step, at best. The fact that Christ became a man, and thus became a part of nature himself, does not diminish my respect for creation but, rather, enhances it. And we don’t have to bring humans down to the level of apes in order to raise apes to a level above those other aspects of nature that don’t exhibit any form of consciousness or self-awareness.

Compared to other Criterion titles, Koko: A Talking Gorilla is surprisingly bare-bones; there is just the film and a short interview with Schroeder, in which he looks back on how the film was made. Considering that almost three decades have gone by, and many of the personalities involved are still very much alive — including Koko, who has her own website — you would think they could have touched on what has happened in her life since then.

At any rate, the film is definitely worth a look. But there are times when I wonder what a director like Grizzly Man‘s Werner Herzog would make of this material. In fact, I am reminded of Herzog’s documentary Echoes from a Somber Empire (1990), which ends with a shot of an elderly chimpanzee smoking a cigarette.