In some Christian circles many people still wonder what to make of the young wizard Harry Potter, whose supernatural adventures have sold more than 100 million novels in 46 languages and set opening-attendance records at the movie theatres. What is the spiritual impact on children?

In some Christian circles many people still wonder what to make of the young wizard Harry Potter, whose supernatural adventures have sold more than 100 million novels in 46 languages and set opening-attendance records at the movie theatres. What is the spiritual impact on children?

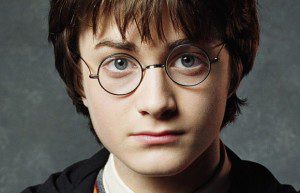

Harry is an orphan whose parents, a witch named Lily and a wizard named James, died defending him from the evil Lord Voldemort. Harry grows up with hostile relatives who scorn magic and hide the truth about his parents from him. But the week before Harry’s 11th birthday, a flock of owls brings him letters inviting him to the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. There, Harry and other children who were born with magical abilities study the history of goblins, the mixing of potions, and the taming of fantastical beasts. Harry and his friends also investigate a series of mysteries that tie back to Voldemort.

To some, Harry Potter is the best thing to happen to children’s literature since C. S. Lewis invented Narnia and J. R. R. Tolkien told stories about hobbits; but to others, he is the literary equivalent of junk food. To some, he is the embodiment of courage, loyalty, and compassion; to others, he is selfish and dishonest. To some, he is a hero whose exploits have got children excited about reading again; to others, he is a dangerous figure who might lure children towards greater involvement in the occult.

British author J. K. Rowling has written four novels in the series so far, and she plans to write three more. To raise money for charity, she has also written two spin-offs that are supposedly replicas of Hogwarts textbooks. The books offer a richly detailed world in which magical folk share a unique history, play their own sports (especially Quidditch, a sort of soccer match on flying broomsticks), and grapple with an unusually bizarre form of pluralism (should werewolves be classified as beings, who have legal rights, or as beasts?).

Unlike Lewis and Tolkien, who sometimes explained their faith in great detail, Rowling has mostly kept quiet about her beliefs. She has said she is a Christian and believes in God, and that she attends church. In an interview with The Vancouver Sun, she said it suits her to keep mum about her beliefs, “because if I talk too freely about that, I think the intelligent reader, whether 10 or 60, will be able to guess what’s coming in the books.”

Several prominent Christians have defended the books against charges of stirring up interest in the occult. Charles Colson has said the magic portrayed in the stories is “mechanical” and not “occultic” — wizards wave their wands and perform all sorts of tricks, but they do not come into contact with anything resembling the demonic world. Alan Jacobs, professor of English at Wheaton College, concurs; he has compared the magical skills of Rowling’s wizards to the futuristic and very improbable technology that science fiction shows like Star Trek rely upon. And the editors of Christianity Today encouraged parents to read Harry Potter with their children.

But not all Christians support the series. Richard Abanes of California, author of Harry Potter and the Bible: The Menace behind the Magick, says Potter’s supporters have missed the real danger of the books, because “none of them have [sic] any knowledge or expertise in the field of occultism.” He says the magic portrayed in the Potter books is so similar to the real-life version, it might as well be the same thing; children whose curiosity is piqued by the books could go to the library — just as the kids at Hogwarts do — and learn more about astrology and other practices that are forbidden by the Bible.

“I think the harm that [the books] do is to further desensitize society and even Christians to the idea of witchcraft and magic, sorcery and spellcasting,” says Abanes, “so that when other things that are not as benign come along, that are pagan, they’re accepted.”

Other Christians, however, think such criticism is exaggerated. Connie Neal, also from California, is the author of What’s a Christian to Do with Harry Potter? She says it is important to accept the worlds that authors create on their own terms, and to separate fantasy magic from real occultic magic, unless the story explicitly connects the two. Otherwise, she says, Christians would have to reject the works of Lewis and Tolkien, who derived much of their material from pagan myth.

Neal says the Potter books may actually expose the dangers of dabbling in the occult. In the first book, a pair of centaurs say they don’t want to get involved in the fight against evil, because everything has been foretold in the stars — but a fellow centaur challenges their complacency. “That’s the real danger of astrology — it’s fatalistic,” says Neal.

She also cites a subplot in one of the following books, in which Voldemort lures a susceptible child into doing his bidding by pretending, in effect, to be an angel of light. “That’s one of the best biblical representations of evil I have ever seen,” says Neal. “Parents can use that to motivate their kids on a heart level to not to want to have anything to do with witchcraft in our world.”

But Rowling’s critics are not only concerned with her portrayal of the supernatural. Abanes says the books promote a selfish and relativistic morality at odds with the moral world view of Lewis and Tolkien. Most of the characters, including the adults, break or bend the rules, and the “good” characters often get away with it — in fact, they even seem to be rewarded for it. He also points to the lies the children tell when their teachers confront them.

It would be “naive” to expect heroes to be consistently good, counters Martin Friedrich of Edmonton, a professor of English at North American Baptist College. “There are characters in the Bible who aren’t good, and even good characters do horrible things,” he says. “And just as the Bible allows us to read about evil deeds, to develop a greater understanding of who we are, I think literature can give us somewhat of the same understanding, of the world, of ourselves, and of our relationship with other people.”

Neal says breaking the rules may even be necessary sometimes — for example, lying to the Nazis to save lives. Neal also points to the willingness of Harry and his friends to sacrifice themselves to protect their school. “Sometimes you set aside lesser rules for the greater good, and sometimes that’s a principle that we really need.”

Some Christian experts argue that parents should be less concerned about references to magic and focus more on the way these books can help children to cope with their fears. Carolyn Whitney-Brown says she first read the books when her daughter became friends with a young Potter fan who was dying of leukemia. Children who have had personal struggles with pain and bereavement are not always able to talk about their own experiences, “but they could talk about Harry’s,” she realized.

Whitney-Brown, who has led adult workshops on the Potter books, says children already know they live in a morally confusing world. Seeing Harry resist the urge to repay evil for evil — for example, he prevents the death of the man who betrayed his father — can help them to find their own moral compass.

“Dealing with ambiguity is one of the most central tasks of growing into maturity,” she says. “So if Harry has to do that, that’s not confusing for kids. That’s reassuring.”

Books mentioned in this article:

-

Harry Potter and the Bible: The Menace Behind the Magick by Richard Abanes (Horizon, 2001) ISBN 0889652015

-

What’s a Christian to Do With Harry Potter? by Connie Neal (WaterBrook, 2001) ISBN 1578564719

Peter T. Chattaway is associate editor of BC Christian News and has written about faith and pop culture for The Vancouver Sun, Books & Culture, Christianity Today, Bible Review and Beliefnet.com.

— A version of this article was first published in Faith Today.