REALITY ISN’T what it used to be. For whatever reason — premillennial anxiety, post-modern rootlessness, the increasing verisimilitude of special effects — filmmakers are increasingly obsessed with the notion that the real world is, in fact, unreal. Last year gave us The Truman Show and Dark City, in which human protagonists awoke to discover they were trapped in cages under someone else’s watchful eye. Similar themes may surface next month in The Thirteenth Floor.

REALITY ISN’T what it used to be. For whatever reason — premillennial anxiety, post-modern rootlessness, the increasing verisimilitude of special effects — filmmakers are increasingly obsessed with the notion that the real world is, in fact, unreal. Last year gave us The Truman Show and Dark City, in which human protagonists awoke to discover they were trapped in cages under someone else’s watchful eye. Similar themes may surface next month in The Thirteenth Floor.

The Matrix is one of the more visually inventive entries in this genre, and it is already the year’s biggest success story, having raked in over $120 million in just a few weeks. (Like Payback and Analyze This, the next-biggest hits of the year, The Matrix is rated R, which would seem to put the lie to conservative claims that PG-rated fare does best at the box office.)

Moreover, people are not only seeing this film, and seeing it more than once; they are talking about it, and about the ideas it explores. For all its comic-book action, The Matrix also comes closer than its implicitly Gnostic predecessors to espousing an explicit theology of sorts, and it even throws in a few biblical references for good measure.

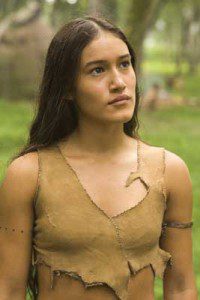

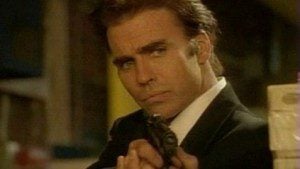

In fact, I can’t remember the last time I saw a Christ figure as fully developed as Neo (Keanu Reeves), the hacker with a regular office job who gets into trouble with some suspiciously lifeless government agents. Help comes in the form of shadowy figures with names like Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne) and Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss), who tell Neo that he’s living inside something called “the matrix” — a world in which work, church and other alleged avenues of conformity have conspired to hide from him the fact that he was “born a slave.”

Morpheus offers Neo the chance to learn the truth about his world, and Neo accepts — discovering, in one of the most unexpectedly freaky sequences in recent memory, that he is one of billions of people trapped in gooey, amniotic pods and attached, through cables that plug into their bodies at nearly every joint, to a global computer network.

Humanity, it turns out, faced a crisis in the 21st century when its machines became too intelligent; humans “scorched the sky” to deprive the machines of their solar power, and in return the machines decided to feed off of the human body’s bio-electricity, effectively turning people into batteries. And, to keep their subjects distracted, the machines have programmed an artificial shared reality into everybody’s minds.

Morpheus is the leader of a real-world resistance group stationed aboard a hovercraft named the Nebuchadnezzar, with ties to a humans-only refuge called Zion. He suspects that Neo may be “the one,” the person who, it was foretold, would have an innate ability to manipulate the artificial universe from within, provided that he knew how to harness his own powers. And so Neo’s training begins.

The Wachowski brothers are certainly a stylish pair of directors. Nearly every shot is a carefully composed, digitally enhanced, cyberpunk labor of love. Indeed, the film’s flashy artificiality threatens at times to overwhelm whatever substance the film does have. But ultimately, it points to a higher reality, albeit one with questionable elements.

Early on, Morpheus asks Neo if he believes in fate. Neo says no, because he doesn’t like the idea that he is not in control of his life. But even after Neo leaves “the matrix” behind and enters the so-called real world, he finds there are still forces beyond his control, guiding his every move with, perhaps, the help of a miracle or two.

Unfortunately, the real world also turns out to be a rather depressing place: if you’re not on the run from killer robots, you’re eating bland, tasteless food. One character cuts a deal with the machines, offering to betray his comrades in exchange for a cushy life back in “the matrix.” He argues, not unreasonably, that if life is nothing more than a series of sensory experiences — if, as Pink Floyd put it, all you touch and all you see is all your life will ever be — then the relatively consistent pleasures of “the matrix” are preferable to real life.

The film, however, ultimately casts its lot with the real world, and largely because its heroes are in touch with an even higher reality. But they face a different sort of temptation, namely the smug superiority that comes with their special form of knowledge. The liberated humans aren’t all that fond of their captive brethren — one refers to them, derisively, as “coppertops” — and the film climaxes with a series of over-the-top battle scenes in which Neo kills dozens of his fellow humans without giving the moral implications of his actions any real thought. (Even Terminator 2 took time to assert that killing people is wrong.)

Moreover, one resistance fighter espouses the view, common to other neo-Gnostic films, that spontaneity is the key to freedom: “To deny our own impulses is to deny the thing that makes us human,” he says. The film ends by laying its philosophical cards on the table: the ideal world, we are told, is one “without rules or controls, without borders or boundaries.”

But this is inadequate, to say the least; without borders, how can we know which impulses are right and which are wrong?

Morpheus is right in one respect: we are born slaves, but we are slaves to our own sinful nature, and without a savior — preferably one who’s got better things on his mind than blowing us away — no amount of self-indulgence can set us free.

— A version of this article was first published in BC Christian News.