Like most of us, I read The Great Gatsby in high school, and although I forgot most of the plot, I remember the elusive feelings that the book evoked, and liking them. I was surprised, then, when the movie mesmerized me, but also left me feeling kind of sick.

I can see the source of the film (and book’s) attraction. The green light perpetually burning on Daisy’s dock is a powerful sign of human desire, reaching, perpetually reaching – for another plane of human existence, for a life that is more real, more moving, more beautiful. This is the desire at the source of all our other feelings of attraction; it is the desire that must keep growing, infinitely. Thus the line that everyone remembers: “Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter – tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms further…And one fine morning—“.

The grand, yearning sweep of Gatsby’s desire seems to awaken the beautiful imagination that also sleeps in me and in you, which believes in the power of one’s own destiny, and thirsts for a pure, all-demanding love. This imagination is confident that even the past can be set right. Gatsby’s desire even seems to bear the mark of humility and self-sacrifice. When Gatsby first kisses Daisy, he freely limits the scope of his continually ascending longing, permanently anchoring it to one particular flesh-and-blood human being. He knows that “when he kissed this girl, and forever wed his unutterable visions to her perishable breath, his mind would never romp again like the mind of God. … At his lips’ touch she blossomed for him like a flower and the incarnation was complete.” Even when Daisy betrays him and marries Tom, Gatsby remains faithful, dedicating his life and ambition to his love for her. The story ends with Gatsby’s act of self-sacrifice that leads not only to his death, but also to the ignominy of a name slandered by Daisy’s crime. Gatsby knew Daisy’s weakness, but loved her anyways, never giving up hope in the power of his love to carry them both upward into glory. Understandably, Nick designates Gatsby as “the most hopeful person [he] ever knew,” a tragic hero.

Perhaps Augustine’s hermeneutic of suspicion has too deeply infused my perspective, but I couldn’t help but associate Gatsby’s desire with Augustine’s critique of the “philosophers of this world,” who “could see that which is, but they saw from afar” (Tractates on John 2.4.3). These “philosophers” correctly perceive the outlines of what human beings in truth desire: a transcendence that is also humble and self-effacing, a redeemed past, a pure love, an indomitable hope. But they become invested in their own distance from these ideals. Because they always see “that which is” from afar, what do they actually see? The spirit of transcendence that they worship disguises itself in the garb of infinity; it promises escape from the limits of oneself. But what this spirit masks, oh so subtly, is that these ideals are only the projection of men’s own desires, dressed up in the trappings of truth. The sign of the lie is the investment in distance. The false distance that human beings construct to protect themselves from their ideals and from other people obstructs awareness of the refreshing yet terrifying distance that truly lies between me, and what exists outside of me – that which I cannot predict, manipulate, or keep safely away.

Gatsby refuses to let Daisy actually draw near to him, even at the end, when his “hopefulness” can’t accept that she probably won’t call. He refuses to let his vision of her, and his vision of the past and the future, be burst open by the facts; he can’t let his desire surrender and conform to the people and events that approach him. “My life has got to be like this,” Gatsby tells Nick, pointing a finger to the sky. “It’s got to keep going up.” His desire pretends to be infinite, but ironically, because it never attaches to someone or something up close, it never breaks out of the confines of Gatsby’s imagination, beautiful as this may be. Gatsby’s selfishness is more hidden than Daisy and Tom’s, but all of them are essentially alone. Perhaps Fitzgerald did perceive this claustrophobia. Both book and film conclude: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

By a happy coincidence, I read T.S. Eliot’s The Cocktail Party the day after seeing The Great Gatsby. The character Celia speaks directly to the hopelessness aroused by Fitzgerald:

…Can we only love

Something created by our own imagination?

Are we all in fact unloving and unlovable?

Then one is alone, and if one is alone

Then lover and beloved are equally unreal

And the dreamer is no more real than his dreams.

And yet, in her new awareness of solitude Celia is still left with “the inconsolable memory / Of the treasure I went into the forest to find / And never found,” as well as “the shame of never finding it.” The way out of the forest of our isolating fantasies cannot be the abandonment of the vision that sent us into the forest in the first place. Cessation of desire is no solution to the problem of desire. Unlike Fitzgerald, Eliot knows that “disillusion can become itself an illusion / If we rest in it.”

The claustrophobia that Fitzgerald leaves us with is not worthless, as long as we don’t get stuck in it. In Eliot’s words, it “only brings you to the point at which you must begin.” In contrast to Gatsby’s fixed, ever-reaching, beautiful imaginations into the distance, Eliot advises a different way of journeying forward. “Every moment is a fresh beginning,” and “life is only keeping on” … and “somehow, the two ideas seem to fit together.” Human beings do journey forward by their ever-growing desire. But right desire daily surrenders and conforms to the happenings and people whom we greet as strangers. And it perseveres in fidelity to a decision even when the green light of attraction has disappeared into darkness. This way means loneliness, Eliot writes, but it also means communion, which we must be schooled to desire. Our hope is that we are able to ascend, not to Gatsby’s seductive vision, but away from “the final desolation of solitude in the phantasmal world” (Eliot).

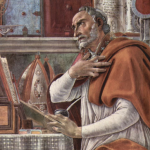

[Picture of Gatsby Cast from Wikipedia]