By Tim Weinhold

(Originally published April 5, 2013)

A meaningful portion of the New Testament was written to help followers of this new Christianity ‘religion’ (more accurately, this new anti-religion) better understand the ways in which their faith required them to live differently from the surrounding culture(s). The Apostle Paul, in particular, often focused his readers on practical ways in which the gospel of Christ called them to live in opposition to various cultural norms.

In the two millennia since, this continues to be one of the pressing challenges for the Church — and for committed Christ followers. This is especially true because, when it comes to guarding against the encroachments of culture, we humans suffer from at least two proverbial problems: we are like fish who swim unaware of water simply because it is omnipresent, and like lobsters who end up boiled because the water temperature rose so gradually as to be imperceptible.

This is, unfortunately, pointedly relevant for 21st century Christian business people. Over the past forty years, much of American business (and, in turn, business around the world) has embraced the idea that the overarching purpose, the highest priority, of a corporation is to maximize the wealth of its shareholders — a conception of business generally referred to as ‘shareholder value maximization.’

This idea was advanced, most famously, by Milton Friedman in his widely quoted 1970 treatise in the New York Times, “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits.”

Also influential was a 1976 academic paper, “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure,” published in the Journal of Financial Economics by professor Michael Jensen and Dean William Meckling of the Simon School of Business at the University of Rochester. The authors argued that CEOs might be tempted to use their leadership position to advantage senior

management at the expense of shareholders, e.g., by investing in a fleet of corporate jets when the money might otherwise have funded dividends. In a particularly glaring example of the cure being worse than the disease, they proposed that CEOs should be given large stock option grants so that their economic upside from share price gains would far outweigh any competing considerations.

Wall Street leaders immediately understood that they stood to benefit greatly — in both money and influence — if these ideas were widely embraced. If the historic purpose of business could be diverted from serving customers to serving shareholders, and if CEOs could be compensated to ensure that their primary focus would be on share price, then Wall Street’s stewardship of what had previously been largely a financing/investment adjunct to business would become vastly more important. Wall Street itself would move from the periphery of business to its very center. And among the many pragmatic benefits for Wall Street: their preoccupation with short-term earnings, now embraced and reinforced by CEOs, would lead to increasingly-rapid stock trading, eventually overthrowing the much-less-lucrative (for Wall Street) traditional practice of ‘buy and hold’ investing. Not surprisingly, Wall Street threw its considerable weight behind shareholder value maximization and stock-based compensation for senior management — and today both are at the heart of the prevailing cultural understanding of the purpose and practice of business.

This conception of business is, however, deeply at odds with the view of Scripture. In fact, it operates decidedly at cross purposes to God’s good work in the world. But because the shareholder value maximization conception is so pervasive — and because the church has failed to articulate the biblical alternative — even devout Christian business people are deeply influenced by the larger business culture’s demonstrably unhealthy conception of business.

This shareholder-centric conception not only dramatically diminishes the good God intends business to effect, but it slowly bleeds the life out of business itself. Profitability, growth, innovation — all are eroding under a flawed, anti-biblical understanding of business. In turn, both Christian and secular business people, unknowingly practicing a corrupted conception of business, struggle to steward business engines that are, in subtle and not-so-subtle ways, losing their vitality.

This blog, and associated essays, will address these two topics — the dangers and drawbacks of shareholder value maximization, and Scripture’s alternative conception of the purpose of business — with, we hope, thoughtfulness and insight. But because these are big and complex topics, we will be doing so in (relatively) bite-size pieces.

Note also that we intend to anchor our explorations both in Scripture and in the best of contemporary business thought, including from such highly-regarded authors as Peter Drucker, Jim Collins, Fred Reichheld, and Michael Porter. And, of course, we will look closely at the primary alternative (secular) conception of business, ‘stakeholder theory,’ as propounded by R. Edward Freeman and others. Here’s a foretaste of all that as we close this first blog entry.

The most compelling critique of shareholder value maximization (and stock-based executive compensation) is offered in a wonderfully astute 2011 book, Fixing the Game, by Roger L. Martin, dean of the business school at the University of Toronto. We will deal more thoroughly with Martin’s book and critique in a subsequent posting(s). But here is one of the especially telling arguments he makes — that shareholder value maximization fails on its own terms. Martin marshals compelling empirical data demonstrating that shareholder value maximization fails to accomplish the very thing it intends, i.e., to make business more efficient and profitable and, in turn, more effective at increasing the wealth of shareholders.

During the middle years of the 20th century (1933-1976), the period when American corporations were the envy of the rest of the world and leaders in virtually every industry — and, importantly, the period immediately prior to the embrace of shareholder value maximization — total real compound annual return on the S&P 500 was 7.5%. Since 1976 the return has dropped to 6.5% (nearly a 15% decline in compound rate of return). Martin concludes: “Shareholders did worse, not better, in the shareholder value era, and several prominent companies (including Johnson & Johnson, Procter & Gamble, and Apple) demonstrate that an effective route to genuinely increasing shareholder value lies in rejecting rather than embracing the prevailing theory.”

Why should this be? The answer, as it turns out, is distressingly obvious. The easiest, quickest way to (temporarily and artificially) boost earnings, and stock price, is to cut costs, for example by skimping on R&D, or to chase ‘bad profits’ (Reichheld) that destroy brand equity. Over time these share-price-driven measures sap the vitality of the enterprise —and eventually growth, innovation, profitability, and share price, necessarily decline.

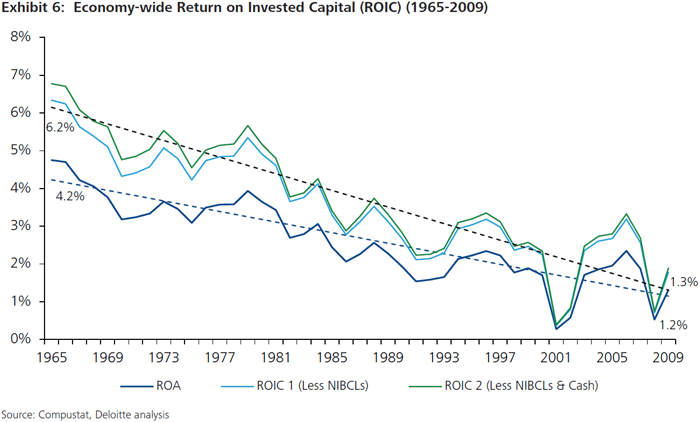

The net result of our embrace of a flawed and anti-biblical understanding of the purpose of business is displayed especially emphatically in Deloitte’s Shift Index, where we see the disastrously declining Return on Assets and Return on Invested Capital performance of large U.S. firms over the past four decades.

The very strategy meant to improve business performance, and shareholder outcomes, continues to dramatically erode that performance instead. But there are other important downsides to shareholder value maximization. We’ll be looking at the full spectrum of these effects in postings to come.