We’ve seen it before: the “I’m leaving Church but I still believe in Jesus” manifesto. Behind such testimonials, interviews, and blog posts is the false assumption that one can have the true faith without the Body that was saved by the Founder of that faith. As faithful Christians know, being in Christ means being in His Church. Yes, we are transformed by God’s grace and called to holiness, but we also realize we are in a flock with other sinners.

Moreover, many will notice that leaving the Church and thus her instruction can often lead to the eventual abandonment of Christ altogether. When we start to define Who Jesus is and what He demands of us on our own terms of comfort and preference, we create an idol. But the first step can be a severance from the Body of Faith. We who are convinced by the truth of the Scriptures may scratch our head when we see these “spiritual not religious” discourses, which seem to be the new “holier than thou” statements.

I myself ponder on whether they have more to do with error or more to do with a failure of will. I’ll grant that there are some who become intellectually convinced of other faiths, but I dare say that many of the abandonment testimonies seem fueled more by embarrassment and bad experiences. “These people who claim to be God’s treated me, my friend, and/or that group of people badly,” the trope often goes, “This is simply too much. I am going to escape hypocrisy. I am leaving.”

I wonder how many articles dealing with grievances against the church’s behavior and mistreatment from her leaders would dissipate if people were actually part of other groups and societies these days. Obviously, the church has to be a witness to the world, but many of the complaints about how certain church members treated a person are pretty universal problems found in any organization: humans in groups can be jerks, make mistakes, have blind spots, and mishandle all sorts of cases. Many of the “I’m leaving or taking a break from church because people hurt me” manifestos could just as easily been authored about the local Ruritans, Kiwanis, Lions, Rotary, Garden, or Women’s Club. But few under the age of 40 participate are in such societies any more.

If more Christians were in voluntary associations, they may have a greater awareness of some common trends in human depravity. Abuse abounds wherever people congregate. It doesn’t matter if there’s a cross up front. People inflict hurts large and small upon other people.

The dearth of Millennials in little platoons, associations where they would rub shoulders with everyday humans in their own locality, cannot be breezily dismissed, even by non-Christians. It leads to social inexperience, emotional immaturity, and an all-round thin-skinned character, which in turn leads to a jejune understanding of what it takes to put up with people, much less love them. Civil society decays. Imposition of will becomes the word of the day. The replacement of manners and etiquette with political correctness is just one visible result of this unfortunate trajectory. After all, if people cannot be limited from bad public behavior by virtue or a sense of honor (and by extent shame), they will have to be managed by positive law. And this positive law will cater to the thin-skinnedness of the most powerful parties.

As Alexis de Toqueville pointed out, it is the discourse and bonds of voluntary associations that helped early Americans fend off several perilous excesses springing from democracy. Toqueville noticed that there are inherent dangers and drawbacks in every political structure; democracies can degenerate into a tyranny of the majority as well as a radical egalitarianism that refuses to discern good from bad. A healthy civil society with many voluntary associations prevent such problems, making the society healthier on the whole.

However, so many people these days join self-selected cliques or interface online at a distance (and thus easily evacuate in difficult circumstances), that they don’t have to exercise true patience with people. We can simply unfollow someone or block their posts from our newsfeeds. We cannot suffer the trouble of others. Call it what you will: “relational hyperefficiency,” laziness of soul, acedia.

It’s a kind of sloth; we slouch toward isolation.

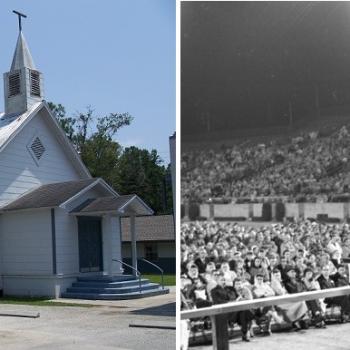

In fact, the Church is one of the few remaining bodies today where people–committed to the same Person, behavior, and doctrine–are “forced” to live in peace with one another. It is actually her witness to an atomizing and alienating culture.

So, before you post that piece you wrote about abandoning church membership or before you share that apostasy testimonial, ask yourself a few questions. Is Christianity really true or not? If it really is true, do I interpret my experiences through that truth or do I try to alter reality based upon the emotions I feel from my experiences? Am I simply failing to exercise long-suffering? Am I just experiencing a shift in theology? Should I therefore seek out a different church home rather than abandon Christianity altogether? Is my local congregation an abusive religious sect? If there isn’t any significant structural difference between the governance of my congregation and abusive sects, do I need to reevaluate my ecclesiology?

Because, in the end, the Truth is what will remain. Christ Jesus, the Truth Incarnate, has brought His people in union with Himself and thus by necessity with one another. He does not fail like His fallen creatures do. If we really believe that and teach that, declarations of self-excommunication seem a lot less appealing.