All over Europe today, “religion plays a role of the epicenter of cultural resistance to the new, the fluid, the strange, the unknown”. An interesting diagnosis of the state of the continent from Petr Kratochvil, director of the Institute of International Relations in Prague, who also warns that the Churches “are not really that important” any more “in influencing moral decision-making” and in that sense are losing the “culture wars” currently being fought in Europe all the way from Ireland to Poland.

After a “very ambiguous” and “rather complex” relationship of several decades between the EU and the Churches “the edges are becoming softer now and the dialogue is more fruitful and more intense”, said the Czech IR expert in a recent interview with New Eastern Europe.

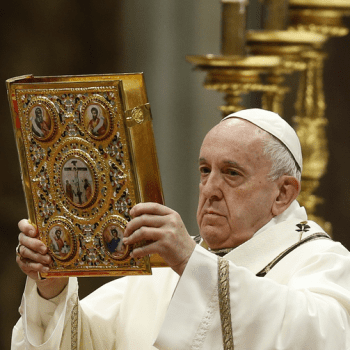

The interfaith responses to the London and Manchester terrorist attacks show “the visibility of the religious communities across the EU is growing”, continued Kratochvil. “Suddenly, the idea of religion being visible in the public is again – at least under some circumstances – acceptable in the EU”: thanks in large part to the blossoming of the effects of the “long-term positive assessment of the [European] integration process” undertaken by popes since Paul VI in the 60s.

Not that this heightened visibility is necessarily leaving all European bishops in a very positive light. Especially, said Kratochvil, the ultra-conservative prelates of Poland and the Czech Republic: countries in which “the Church has unfortunately taken the anti-refugee, nationalist side, while still claiming their position is rooted in Christianity”. Without asking, too, what the Czech expert calls the “real question” behind the migrant crisis still shaking the continent: that is, “Is Christianity a conservative movement, or a radically open – even revolutionary – one?”

But precisely because of the particularly bitter conservative backlash they have experienced, Poland and the Czech Republic are the countries in which Kratochvil has been able to discern an even more interesting phenomenon being felt continent-wide. In the Czech Republic, he said – “probably the most secular society in the world” – “people still look back to [an] idealised and romanticised Christianity, a sort of cultural Christianity”.

“People do not really go to church, do not even believe in God, but some have recently started publicly saying that they are Christians”, observed the expert. “This, of course, does not mean that they pray to Jesus, but that they do not like Muslims“.

Base instincts these of looking back in times of crisis to a supposedly more certain past to which lawmakers have played unashamedly, according to Kratochvil: as in the legislation that passed in the Czech Republic a few years ago proclaiming Good Friday a public holiday, and that much as a way of strengthening the country’s “Christian” identity.

“[L]ess than 20 per cent of people belong to the Church and less than five per cent go [to] Church regularly. And yet, we suddenly turn back to the past and say that we are Christians“, observed the academic, lambasting the legislation as “absurd” and warning that such restorationist tactics have little future in today’s Europe.

“[I]n the end the Church will lose” the cultural battles in which it is immersed – on everything from welcoming migrants to accepting gay marriage – “and then it will have to change not only its strategy, but also its focus”, warned Kotochvil. “The Pope has spoken about it time and again”, but the Church in Eastern Europe “does not want to listen to him”.