Ordinary Time

St. Theodore of Tarsus

The Edge of Elfland

Concord, NH

Dearest Readers,

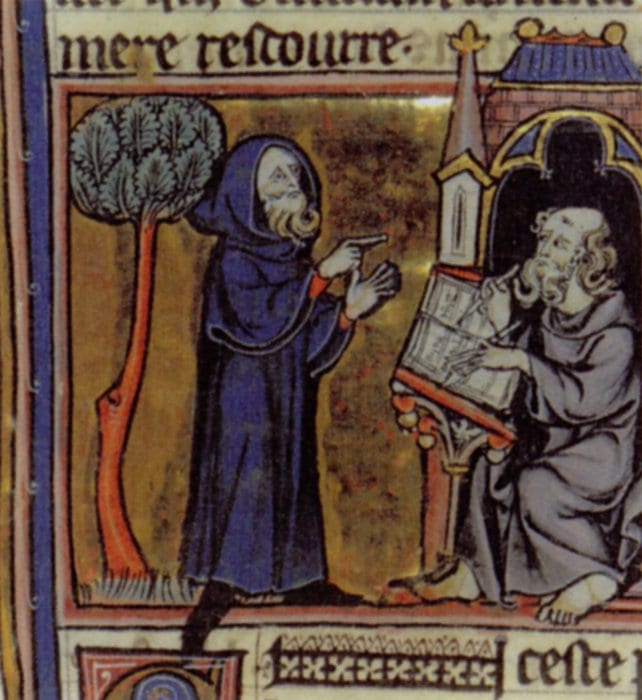

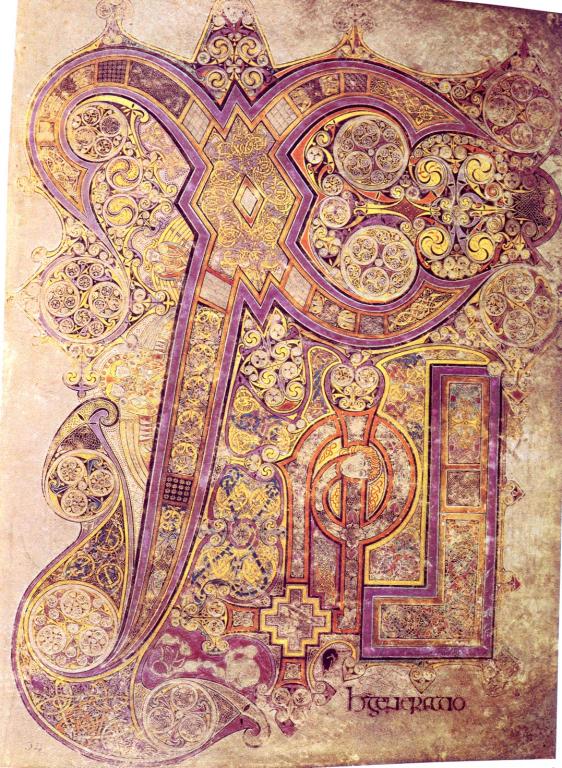

It was about two years or so ago I was first introduced to director Tomm Moore. Somewhere around St. Patrick’s Day and The Secret of Kells was available on Netflix. The boys and I watched it and while they, at roughly two, faded in and out, I was enraptured. I loved the storytelling, I loved the animation, and, most of all, I loved the connection of Faërie to the Faith. For those unfamiliar with the film, it tells the story of the writing and, more importantly for the film, the illuminating of The Book of Kells, an illuminated codex of the four gospels. As Aidan brings the unfinished book to Kells from Iona, Viking raiders following in his wake, he meets the nephew of the abbot, young Brendan. Brendan takes immediately to Aidan and wants to do anything to help him, so he ventures outside the walls of the village and into the forest. There he meets the fairy, Aisling, defeats the pagan god Crom Cruach, and ultimately brings back a treasure which makes completing the book possible.

There is much more I could rehearse about this film, but I won’t for now. I’ll simply tell you to watch it for yourself. One of the chief things I love about this film is its subtle Catholicism. No one actually says what is in the book. They almost pretend as if it is filled simply with illuminations and not with words. Of course, the Chi-Rho page is mentioned and is vitally important, but no one ever explains that the Chi-Rho is important precisely because those are the first two letters of the word Christ in Greek. One could claim that the film is not really all that Catholic. No one ever mentions God or Jesus or the Bible. And yet, the way the book is said to drive the darkness away, even the way Aisling the fairy seems to understand it, shows precisely that it is the coming together of the two books––the books of Creation and Revelation––that is the source of its beauty and thus its power.

In another of Moore’s film’s The Song of the Sea the Catholicism is even more subtle and yet, I think, immanently present throughout. The film takes place in the late 1980s, the time of Moore’s childhood, and follows Ben and his sister Saoirse as they discover that their mother’s disappearance and the strange things that have happened to Saoirse are connected, that Saoirse is one of the fairies, a selkie to be precise, just like her mother before her. As the brother and sister journey through Ireland trying at first simply to find their way back home and then to get Saoirse’s coat, they encounter many obstacles and many safe havens.

One such safe haven is a holy well. Ben carries Saoirse through stinging nettles into a cave containing the holy well which is filled with statues of Mary, rosaries, icons, flowers, and more. As Ben rubs his now itchy legs, Saoirse goes back into the rain and gets some dock leaves to soothe the pain. The imagery is both decidedly maternal, and for that very reason Marian and Catholic. Mothers and women are at the core of this film. Ben and Saoirse’s mother disappears at the beginning of the film; their father’s mother takes them away, thinking she is doing what is best; and the villain of the film, Macha, takes people’s emotions believing this better than feeling pain and grief and sorrow. And thus, in the end, it is little Saoirse who saves them all both the fairies and her own family. That scene of her bathing the wounds of Ben surrounded by depictions of the Holy Mother is so moving that it brings me almost to tears each time I see it.

I don’t know what Moore’s faith is now. The two most recent films he has produced and/or directed, Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet and The Breadwinner, show at least that he has a religious fascination in addition to a love for his native Ireland. Nevertheless, not unlike another director I love, Guillermo del Torro, the mark of Catholicism has been indelibly left on him as it shows itself in The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea. And for that reason, I cannot recommend at least the first two films enough. And I can say that I will be giving both The Breadwinner and his forthcoming Wolfwalkers when I have a chance.

Until then, I will be spending a bit more time with the book that drives the darkness away and with Mary the Mother of God. Perhaps in these trying times, they can help me stay in the light and heal my wounds.

Sincerely,

David