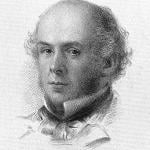

Plato is misunderstood more than read.

Plato is misunderstood more than read.

Thank the Demiurge, a few seek understanding and not just confirmation of bias.

I was once asked about the soul, Plato, and Jesus based on questions from my book When Athens Met Jerusalem … here is my response.

You say:

But, the question for discussion was: what did Plato believe about the soul?

I reply:

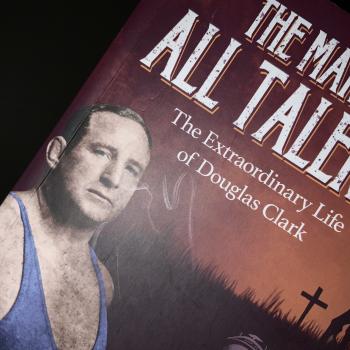

This is a profound question and was the subject of my dissertation now available as a book through UPA . . . so the technical answer here.

You say:

The overall issue with regard to the soul is the production of motion. (As a great Baptist preacher once said: Without emotion, there ain’t much motion.) The bulk of the discussion was about the human soul. Plato believed that in order to have a human soul united to a human body, it was necessary for the soul to be “imperfect.”

I caution:

Don’t import moral imperfection here. This can mean merely “less than.”

You say:

Otherwise it could never unite with the material body. Without a soul, the human body would not be able to achieve things “in the image of God” like creative thought, empathy, and goodwill. But, it is not possible for humans to perfectly reflect God because their souls needed to “cool” a lot before being implanted. We did not find much of this classic Platonism in Chapter 3. What are your thoughts on this particular aspect of the human soul?

I say:

I don’t think “classic Platonism” (assuming we have a good description above) is Plato. Our souls reflect God (ideally) the best they can. That is good. Nobody should think that they perfectly reflect God or the Good. They cannot.

We are always becoming like God, never being God! We fall short of His glory, not just because of sin, but because we are creatures and He is Creator. There is (for Plato) an unbridgeable gulf between God and humankind. He did not anticipate (clearly) the Incarnation, where God became man. We cannot become God.

You say:

Another classic element of Plato’s theory of the soul is the tripartite nature: the rational soul, the spirited soul and the appetitive soul. This description of the human soul is “phenomenologically” helpful. Did we miss your discussion of the tripartite soul?

I say:

The tripartite soul is ONE way Plato talks about the soul. He also breaks it down (in some dialogs) between an immortal or mortal soul. In other places, he speaks of the rational soul and all the rest. In Republic, there is a postulated “small soul” within the rational soul that is also tripartite.

It is important to remember that all of things are images for Plato. Too often we end up saying: Plato thought the soul tripartite. He thought a tripartite soul was a most useful image for the way the soul worked, but not a complete or only image.

You say:

In light of Plato’s view of humans as remarkable but fallible, he had a very practical attitude towards the proceeds of recollection. Every mathematician and scientist at the table was familiar with moments of “intuition” where dramatic insights were obtained without detailed calculations from first principles. Plato was “not crazy” when he proposed the theory of recollection. But, he was also realistic about the accuracy of human recollection. Whenever an insight was obtained, Plato recommended trying to verify it in the actual world. Humans are not capable of infallible intuition, but they are capable of reaching ideas that are true in a remarkable, but largely misunderstood, way. On pages 76 and 77 you seemed to be suggesting that your “recollections” were much more certain than I would have expected Plato to claim. How are explicitly fallible humans able to perfectly recollect anything?

I say:

I am following the “divided line” image in Republic. Some recollections become indubitable (though by no means most!) . . . I am confident that once one grasps 1+1=2 that one cannot doubt it.

Of course (see Timaeus) any “truth” we find about the World of Becoming (the “real world” as we call it) is tentative. Investigation is necessary as is a loose claim to know the truth.

You say:

Understanding what Plato taught is one question; another interesting question is: what is the appropriate stance for a 21st century Christian?

I say:

With AE Taylor (too little read Christian Plato scholar AND apologist), I think a form of Christian Platonism is the best explanation we have for the world.

You say:

Is it useful to distinguish the many parts of the soul?

I say:

It is a useful heuristic device. What is true of the composition of the soul? God knows.

You say:

In spite of some Christian philosophers insistence that “nothing with ‘parts’ can be good enough to be “spiritual,” our personal experience can be discussed in terms of the Platonic parts with profit. I have not read your full book on Platonic Psychology. Do you discuss the full extent of human mental reality? (mind, will, love, hate, hunger, thirst, etc.)

I say:

We have parts and God loves us. God dignified the “parts” by becoming man. He was God-Man (2 natures) and was fully good.

You say:

There is also the question of “substance dualism,” but we did not focus on this issue. There are good Christian philosophers who are dualists, both historically and in the present. Nancey Murphy is not one of them, but she does produce a “viable” argument against eliminative materialism. Even Patricia Churchland, hardly a Christian, has become a “mental realist.” Dualism is no longer “the only port in a storm.” This is not an argument against dualism, but it weakens the stance that we must be dualists or abandon Christianity.

I say:

I am hard pressed to name any Christian thinkers prior to end of the last century who were were materialists. I am underwhelmed by Murphy’s arguments and believe Swinburne has refuted her view. . .

Much of this will depend on how seriously one takes the third leg of the stool of Christian thought (Word, reason, tradition). I cannot understand how God can be “spirit” (as he must be) and leave any gains in adopting materialism for humankind. The argument seems to be “science” no longer needs the soul, but I am unpersuaded.

You say:

While your book on Plato does not mention “pneuma,” we did raise this issue at lunch. Some discussions of the soul conflate this concept with the additional notion of a “spirit.” Both Hebrew and Greek do have different words for these two things. How would you explain the spirit of man? What relationship, if any, does it have with the human soul?

I say:

I think the distinction between pneuma and psycha is overblown. In the development of Greek thought the two terms came to be basically synonymous and I don’t see any reason for a distinction in the New Testament.

Homer begins with a soul that is “wind” and I see that analogy early on in Sacred Scripture as well . . . but then more robust views of the soul are developed. I think a similar process of enrichment of terms takes place over the OT and NT. In other words, I think you have a soul and body. Is the soul in parts? It is useful to think so at times. Is it actually? I don’t know.