Pilgrim Pop Quiz: What’s the oldest Christian pilgrimage shrine in Europe? Hint: It’s associated with St James (Santiago, as they call him in Spain), but it’s not the one from that movie with Charlie Sheen’s dad. It’s in Zaragoza, where the ancient and the thoroughly post-modern meet for tapas, and neither one blinks.

Pilgrimage 2012, Day 7: Madrid to Zaragoza

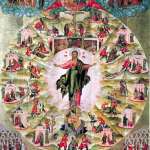

When you say Spain, Santiago, and pilgrimage, everybody thinks Compostela, the purported resting place of St James the Greater, who was said to evangelize the Iberian peninsula. That shrine, just inland from Spain’s northwest coast (the forward brim of the matador’s cap, if like me you were taught to envision the map of Spain in that fashion) has been drawing pilgrims for centuries, as they walk the ancient path known as el Camino, the Way. The scallop shells that litter the nearby beaches were the only souvenirs available to medieval pilgrims, who started wearing them in their hats or pinned to their cloaks as badges of authenticity—been there, done that, got the coquilles St Jacques—just as pilgrims to the Holy Land wore palm branches and were known as palmers. Soon the scallop shell became the universal pilgrim symbol, as St James became the universal patron of pilgrims. For that reason, we’ve named the newly formed pilgrimage society of the Archdiocese of Cincinnati The Companions of St James.

But though we watched The Way on our buses crossing the Spanish foothills out of Madrid (the similar landscape out the windows making it seem like we were watching on a very wide screen indeed), Compostela was not on our itinerary. The shrine we visited has a much, much older story, though a far less familiar one to non-Spanish speaking Catholics. We saw it from a distance as we crossed the River Ebro, an ancient route of Roman conquest at the base of the Pyrenees: the Basilica and Shrine of Nuestra Senora del Pilar (Our Lady of the Pillar), its minaret-like towers one more reminder of the dance of the cross and the crescent in this land.

The shrine honors a miraculous encounter between Mary and the Apostle James the Greater, but as our local guide and the city tourist brochure insist on clarifying, this was no penny ante run-of-Bernadette’s-father’s-mill apparition. It was a visitation. According to a legend as old as the Church, James was holed up in Zaragoza about the year 40, despairing of his mission to convert the Romano-Celtic tribes of the region. So Mary, who was still living, visited him to cheer him on. She did this while remaining at home in the Holy Land at the same time. “It was bilocation,” our guide patiently and matter-of-factly explained, like a science museum docent introducing children to e-lec-tri-ci-ty. And like any good friend, Mary didn’t come empty handed. She brought James a small marble pillar (some odd or end Joseph had left around the house?) and told him to build a church around it. He did, and the Spanish-speaking Church built itself around that pillar. If you know a woman named Pilar, from Mexico or the Philippines or Chile or Spain or East Los Angeles, you know how widely that Church returns the favor.

Pretty soon after Mary’s visit, pilgrims began monolocating to the small shrine where the pillar was ensconced. Later, an image of the Madonna, credited with many miracles, was placed atop the pillar. On all but three days of the month, the image is robed in a triangular mantle—the shrine is in possession of thousands of them, richly embroidered and encrusted with jewels; we got to see Her unmantled, because it was the day each month that celebrates the crowning of the image. Over the centuries, larger and larger churches were built around the pillar, but it has never been moved from the place where Mary set it.

Today, access to the miraculous image and to the pillar is very limited. With a few exceptions, only those of the guild responsible for the shrine may touch the image’s mantle, to change it each day; children about to make their First Communion are allowed to climb a stepladder and touch the hem of Her mantle—as are the members of the Zaragoza soccer team at the start of the season. All other pilgrims—among whom Blessed John Paul II was numbered—must kneel before a small gilded opening at the back of the shrine, where the pillar may be touched or kissed. I placed my wonky knees where so many had been before, in far greater pain of body and soul than mine, and touched my lips to the cool marble. In no other place did I feel so much a part of the long pilgrim parade, the chain of unceasing prayer and praise and petition and thanksgiving stretching back along a camino of 2,000 years.

Many on our pilgrimage consecrated themselves to the Immaculate Heart at Fatima or at Lourdes; I claim the mantle of the Lady of the Pillar. That mantle recalls the earliest known prayer for Mary’s intercession, the 3rd century Coptic Christian hymn known in Latin as Sub tuum praesidium.

Under thy protection we seek refuge, Holy Mother of God;

despise not our petitions in our needs,

but from all dangers deliver us always,

Virgin Glorious and Blessed.

You may recognize it as the root of my mother’s favorite prayer, the Memorare. And praying it, let us hold up for Her protection the Coptic Christians of Egypt, in so much danger today.

The mantled Virgin atop her pillar is everywhere in Zaragoza, an unmistakable image. The New World sent Zaragoza and the province of Aragon the gift of chocolate, and now Mary’s sweetness multilocates wherever you go—on thick bars of chocolate studded with Spain’s plump marcona almonds, on cakes in tins, on the addictive local confection known as frutas de Aragon, fresh fruits simmered in honey, robed in dark chocolate, and wrapped in rainbow colors.

The mantled Virgin atop her pillar is everywhere in Zaragoza, an unmistakable image. The New World sent Zaragoza and the province of Aragon the gift of chocolate, and now Mary’s sweetness multilocates wherever you go—on thick bars of chocolate studded with Spain’s plump marcona almonds, on cakes in tins, on the addictive local confection known as frutas de Aragon, fresh fruits simmered in honey, robed in dark chocolate, and wrapped in rainbow colors.

Our hotel in Zaragoza was as post-modern as the pillar is ancient—a zebra-striped wonder with rooms decorated in tomato-red acrylic and sleek teak, with a sophisticated wine-and-tapas bar in the lobby and a sky car line (the nonfunctioning relic of a World Expo) outside the windows. But the contrast wasn’t jarring at all. Perhaps, like the Zaragozans, we had begun to find bilocation—in time, anyway, if not yet in space—as simple as breathing, as sweet as chocolate. Under Mary’s mantle, we slept.

Our hotel in Zaragoza was as post-modern as the pillar is ancient—a zebra-striped wonder with rooms decorated in tomato-red acrylic and sleek teak, with a sophisticated wine-and-tapas bar in the lobby and a sky car line (the nonfunctioning relic of a World Expo) outside the windows. But the contrast wasn’t jarring at all. Perhaps, like the Zaragozans, we had begun to find bilocation—in time, anyway, if not yet in space—as simple as breathing, as sweet as chocolate. Under Mary’s mantle, we slept.

_____

NEXT: We Lift Our Eyes to the Hills: Over the Pyrenees to Lourdes