I was having a conversation recently with a Korean American friend of mine who finds himself deep in the classical Reformed tradition. In this description, one should realize that the ‘classical’ modifier means that he is not a ‘New Calvinist‘ in the sense that a number of Asian American evangelicals are: passionate, but scared of baptizing babies, while claiming to have a covenantal theology though the truth is that they probably latched onto the likes of luminaries such as John Piper and Tim Keller because their male fragility is most visible in the presence of women whose erotic power and leadership competence are unrepressed. My brother, it seemed to me, had achieved a modicum of integration within his tradition, one that I was never able to find when I was a Protestant (and it was not for want of trying), and found himself in the ecumenical situation of being my roommate at a recent conference we attended together.

Those in the classically Reformed traditions seem to center their theological reflection on the cross and the crucifixion of the Son of God on it, and my friend was no different. In fact, he copped to sympathy with Luther’s ‘theology of the cross’ in the sense that it negates delusions of grandeur. Magisterial Protestants, my Catholic and Orthodox sisters and brothers seldom acknowledge except by way of mockery for schismatic tendencies within Protestantism more generally, are different from each other, which means that it is quite a big deal that someone so sympathetic to John Calvin would cop to a preference for Lutheran theology.

I admit that when I was a Protestant, I was rather promiscuous in my reading of the Reformers and their theological descendants, although I realize now that that was a function of a Chinese Christian sensibility where I cared less about schools of thought than where the movements of my heart were leading me. My Korean American brother, on the other hand, hedged by telling me that it was from a Reformed perspective that he embraced the theologia crucis. My heart went out to him, and seeking to invite him to share in my theological promiscuity, I recommended that he read Hans Urs von Balthasar’s meditations on cruciform negation in Mysterium Paschale. I am not pretentious enough to style myself as the Balthasar to his Barth, but I suppose my sensibilities mirrored that Catholic theologian’s attitude toward his Swiss Reformed friend. I simply wanted my brother to share in our Catholic koinonia, in which all things are ours in Christ, and that he will probably read this post gives me great anticipatory joy, as I do not believe in secrets agendas. Good and wonderful plans for friends should be openly and vulgarly stated.

This conversation made me reflect on my own encounter with the theologia crucis. Luther’s formulation in the twenty-first thesis Heidelberg Disputation has become a truism among educated Protestants: A theologian of glory calls evil good and good evil. A theologian of the cross calls the thing what it is. I remember the first time I heard this statement. It was in a sermon delivered at the now-defunct Mars Hill Church in Seattle, a hipster evangelical church of the New Calvinist persuasion. It was not, however, the infamous Mark Driscoll who preached it. I can’t remember who it was, but it was one of their co-pastors. At the time around 2005, what is still known as the ‘Acts 29 Network,’ a group of churches purporting to write the next chapter of the Acts of the Apostles with a New Calvinist mission, was small and had not consolidated around the term New Calvinism, which was coined in Christianity Today in 2006. One of the churches whose spirituality concentrated more, it seemed, on spiritual practice and ecumenism had a reading list, and it recommended Alister McGrath’s Luther’s Theology of the Cross and Heiko Oberman’s Luther: Man Between God and the Devil.

The argument of both books was that Luther’s theology had to be understood in the terms of his Catholic predecessors. For one, Luther was an Augustinian monk. But for seconds, Luther as much contested as he was influenced by late medieval Latin theology, which had taken on a kind of nominalist and voluntarist spin. I recalled learning about these terms of medieval European history, but as a young graduate student in geography, I really could not have cared less about these philosophical finesses, and I had not yet encountered the Radical Orthodoxy of John Milbank and his students which blames nominalist philosophy — the idea that names are just labels and do not really connote the essences of things — for modern secularism.

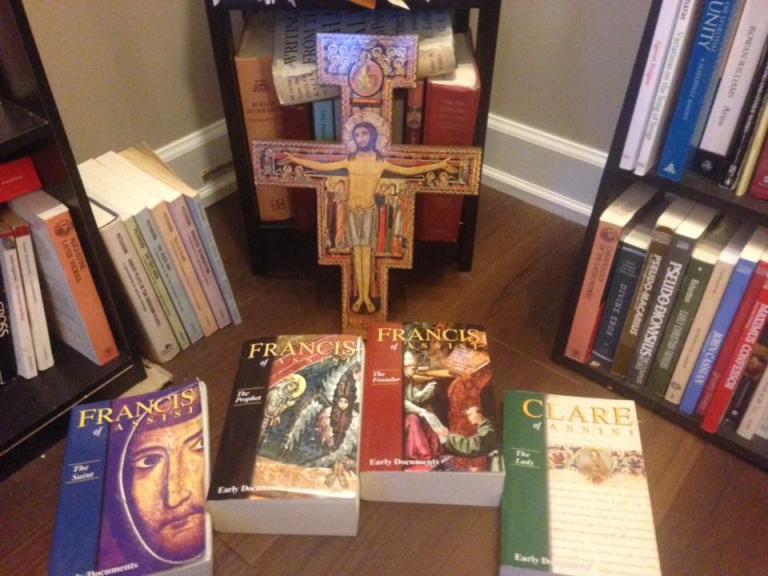

Instead, in what was probably a misreading, I decided that the references in McGrath and Oberman to the Franciscans as those who worked out nominalism and its theological cognate, voluntarism (the notion that God is pure will and therefore totally sovereign), meant that I should go right back to the source: Francis of Assisi. I had three other good reasons to do so. The first was that I had encountered at an Anglican realignment conference a youth minister who had been a Franciscan monk and had told the inspiring story of St Francis hearing God calling him to ‘rebuild his church,’ and he did so physically at the place where he heard it until he realized that there was a broader ecclesial vision to be pursued. The second is that since the early days of my undergraduate education, I had been quite taken with the historian Lynn White’s essay, ‘The Historic Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis,’ which blames everyone in the late medieval Latin Church except for St Francis for murdering the modern environment. The third was pure free association, the foregoing ones being more pretentiously impure transferences. Living in Vancouver after high school, I found that most people in the Cantonese Protestant communities in which I worshipped and attempted in vain to find a girlfriend denied that I had had a life prior to my move to Canada. I was, I insisted, from the San Francisco Bay Area, which is flanked on the north and the south by the counties of San Francisco and Santa Clara, and decided that for reasons of personal identity, I should be invested in the theologies of Ss Francis and Clare of Assisi.

And so it was that I found myself in an evangelical coffee shop in Vancouver sipping a vanilla black tea pretentiously called ‘Franciscan Monk’ with the first of the series of documentary compilations edited by the Franciscans titled Francis of Assisi: The Saint. I had, by this point, become familiar with Francis’s Canticle of the Sun, but I decided that I wanted a more robust understanding of who the man was and how he thought. I therefore started at the beginning. The first thing in the collection is the Prayer before the San Damiano Cross, which I in my evangelical ignorance thought was a standard-issue Latin crucifix:

Most High,

glorious God,

enlighten the darkness of my heart,

and give me

true faith,

certain hope,

and perfect charity,

sense and knowledge,

Lord,

that I may carry out

Your holy and true command. (Francis of Assisi: The Saint, p. 40).

It took me some time to realize that this prayer concerned the story that that ex-Franciscan Anglican youth pastor had recounted, and it struck me immediately as having a completely different vibe from a Protestant prayer before the cross. I was familiar at the time, for example, with ‘The Gospel Song’ that came out of Sovereign Grace Ministries well before the allegations about sexual abuse in their small groups was revealed in a lawsuit, and the best thing about their recording of it is that it is sung by Shannon Harris, the woman who ends up marrying Josh Harris of I Kissed Dating Goodbye fame. The song goes: Holy God in love became perfect man to bear my blame. On the cross he took my sin. By his death I live again.

The theological transference between Francis of Assisi and New Calvinism did not work. Francis’s prayer before the cross does not contain a substitutionary theology of atonement, the notion (as in ‘The Gospel Song’) that Jesus took the punishment for sin on his body such that human persons can reach out in subjective faith to claim this objectively accomplished deed for themselves. The common formulation is that a gospel of substitution means, as Luther puts it in his commentary on Galatians, that the human person ceases to strive for ‘active righteousness’ in the sense of trying win salvation with good works and instead receives ‘passive righteousness’ by having it imputed to them in a legal way by God alone. But that is Luther, not Francis. What was startling for me as a wannabe New Calvinist kid trying to track the sources of my theology back to Francis was that the saint actively advocated an active righteousness. The implication of the cross is that Francis wants to ‘carry out’ the Lord’s ‘holy and true command,’ which is to rebuild his church, which bore out in the next document in the series, which was Francis’s earliest rule for his followers. Not only is it laced with prohibitions about what his little brothers can and cannot do in terms of morality, but it is also framed around the Lord’s prayer for Christian unity in John 17, that they may be one as the Father and Son are one.

Unbeknownst to me, the San Damiano Cross, which I had not at this point even seen with my own eyes, was converting me from my Protestantism. For those of us in the Kyivan Psychoanalysis Study Group in Chicago, we refer to it as an icon, as valid as the icons of the Crucifixion with the three-barred cross in our Byzantine tradition. Indeed, there are some who refer to it as a kind of Byzantine influence in the early modern Italian city-states. My most poignant encounter with it recently is praying a readers’ Jerusalem Matins before it at DePaul University over the last Great and Holy Week this year. It was, we concluded, an icon of the Lord in its own right, though I did not tell my sister and brother Summer and Julian who prayed with me that it had had such a converting influence on my life.

The San Damiano Cross depicts the church and the angels gathered around the Lord who is crucified. But in his crucifixion, our Lord Jesus Christ is victorious, almost emerging in resurrectional splendor from the wood of the cross itself. As is typical of good iconography, Jesus is looking at the viewer. I remember one time in a daily mass setting at a parish near our Richmond home before I got roped into Eastern Catholicism at a temple that was even closer in distance, they used the San Damiano Cross as the processional crucifix. I was struck by that because that Latin parish’s priests are drawn from the Society of the Atonement, the Franciscan order whose founder was responsible for also convincing Catholics and Protestants to engage in a week of Prayer for Christian Unity that is now held annually in January. Searching my heart for why I was moved, I had a conviction as a Protestant wanting to be Catholic at that time that what was being depicted in the San Damiano Cross was truly a negation, a theologia crucis, but a nullification not of ego, but of the ecclesial divisions that have cropped up over the years. Perhaps that claim is overdetermined — there are real theological differences across the oikoumēnē that keep us apart, especially the problem of most Protestants, having had a history of too many debates about what communion is, not knowing what communion is anymore and not caring about it very much and therefore being unable to establish ‘full communion’ with us — but spiritually, I think there might have been something to that. I’m still exploring it.

What I can say is that as the San Damiano Cross hangs above my icon corner, the daily gaze of the Lord upon my heart as he is centered resurrectionally among the people of God reminds me of what it means to be Catholic. I am Eastern Catholic, which means that my orientation toward the Lord takes place in a local autocephalous church from Kyiv that has, like our sister church in Rome, gone global. But what it means to be Catholic is to understand that the distinct practices that I try to enact in my everyday life that might differ from both the Latin Church and my Protestant past are entry points into the universal experience of the world founded in love and laced with the supernatural. The death and resurrection of Jesus Christ is what constitutes this oikoumēnē, and it will continue to do so despite the pretensions of some of the churches on it to colonial and imperial power and the evils those exertions inflict, including the secularizing philosophical and theological forms of nominalism and voluntarism. To be Catholic is to attend to this common inhabitation, to channel the distinct practices of our church to the universal claims of social justice, ecological integrity, a civilization of love, and a revolution of dignity. In this way, what is negated in this theology of the cross is not the ego, forcing myself into the insanity of living only within the free-floating signifiers of the unconscious and being open to gaslighting because of a postmodern praxis of a false universality. Instead, it is the transferences, fantasies, and ideologies of utopic society themselves, that which calls evil good and good evil in Luther’s formulation. A theologian of the cross calls the thing what it is.

These reflections on the icons in my beautiful corner compose the series I am writing for this year’s St Philip’s Fast in preparation for the Feast of the Nativity, beginning on the Old Calendar as I am in Chicago and switching back to the New Calendar when I return to Richmond in mid-December. They are attempts to account for my process of conversion in the Kyivan Church without discounting the Chinese Christianity of my Protestant past. This post is the first.