The following post contains spoilers for the film Ida.

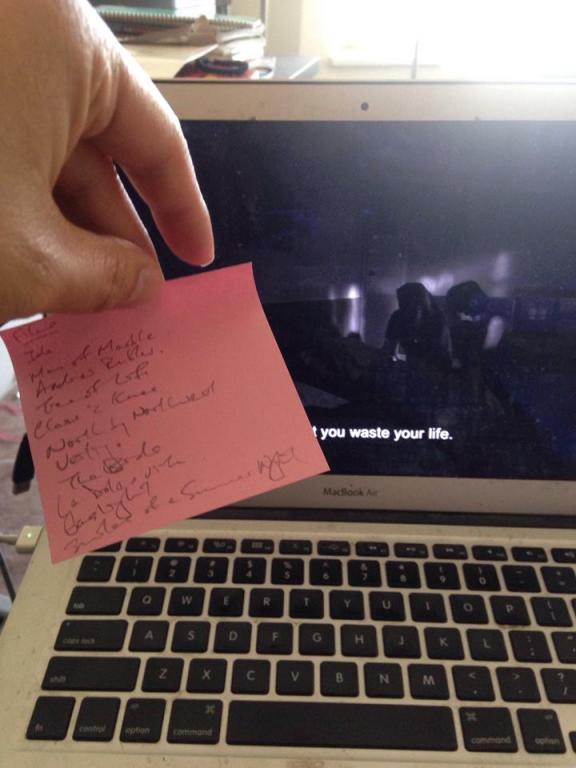

On the occasion of my birthday yesterday, the members of the faction of the Kyivan Psychoanalysis Study Group that I am coming to call my pop psychoanalysis posse – namely, Eugenia Geisel and Grace Yu – each independently advised me to watch a film called Ida. It was, according to Grace, one of her ‘favorite films of all time,’ which is saying a lot because she is always recommending me to watch art house films to supplement my trashy action movie diet. One day, I swear I’ll get around to her Eric Rohmer recommendations – she tells me to begin with Claire’s Knee – but I was disappointed that Eric is not Sax, so I would not be watching old, racist Fu Manchu movies, which I would be more inclined to see because my preferred tastes revolve around the genre of the bad movie.

Having established that I therefore do not ever watch any of Grace’s recommendations for fear of accidentally converting to her bohemian tastes, I watched Ida because Eugenia then separately gave me the same recommendation. Eugenia was a Slavic literature minor in college, and Ida was supposed to be in her required film course. It was cut from the menu at the last moment. Forbidden fruit is the tastiest of all, though, so she enthusiastically boosted its appeal. What this also means is that Ida is a Polish film, the subtitles are in English, and Eugenia saw this as a way of reminding me to watch her favorite film of all time, Man of Marble. That’s next on the list.

There is nothing popular about Ida, which made me wonder why my pop posse saw fit to sneak it into my diet after they did me in with Ariana Grande. It’s a film that moves in silences, still shot after sublime black-and-white still shot. There are prayer scenes, scenes with no dialogue, shots of countrysides, farm sequences, whole minutes filled with clucking chickens. If this is popular culture, then Of Gods and Men is too.

Of course, Eugenia and Grace never said that it was popular culture that they were recommending with Ida, but I still had the concept in mind when I watched it. My research assistant at Northwestern, who is in large part responsible for turning my interest in psychoanalysis from a side hobby to one of my main driving theoretical engines, recently convinced me that Michel de Certeau SJ, whose studies with Lacan and critiques of Foucault should have tipped me off much earlier that I was really interested in psychoanalysis all along, was not that far off when he wrote about popular culture and acts of consumption in his classic text, The Practice of Everyday Life. Certeau’s sense of popular culture is not so much focused on what it is, but on what is done to it.

In Certeau’s sense, popular culture is not just the stuff that’s circulated for trashy mainstream consumption, but the ways in which people take all kinds of images, ideas, and ideologies that circulate through their everyday lives and turn it into something meaningful for their own ways of being. Upon reflection, not only is the Eastern Catholic artist Andy Warhol a paragon of this sensibility with his soup cans and pop art, but so is (as my research assistant reminded me with a smirk) the self-help guru adored by the alt-right, Jordan Peterson. As critical as I am of Peterson’s intellectual shoddiness (though Sam Rocha’s critique ultimately takes the cake for me), most people I’ve met will say things like, I’ve never read Peterson and probably won’t, but if he tells young men to clean their rooms, how bad can he be? What is being done to Peterson there is what Certeau is describing as the consumption practice of popular culture: Peterson is more of a pop icon than an ideologue that is in everyone’s faces, and most people are crafting him into their own image instead of working through what he has to say. If we worked through what Peterson has to say, we’d find Peterson embodying Certeau’s sensibility even more. Peterson’s books are but a hodgepodge of the psychoanalytic theory, tall tales, mythological references, and popular images and sounds that have circulated through his life, which is why Rocha knocks him as the ultimate postmodernist. The point is that anything can be popular culture, as long as its images are popular enough to thread their way into the everyday lives of the masses.

In this sense, it is not so much that Ida is popular culture as much as it is a commentary on the popular culture that circulated through the times it portrays, early 1960s Poland shot fully in black-and-white. What triggered this thought for me while watching the movie was one of the opening scenes in which the protagonist Ida – or that is to say, the novice Sister Anna – is told by her superior to seek out her aunt, Wanda Gruz. This scene reminded me of Slavoj Žižek’s oft-repeated commentary on The Sound of Music, in which the Mother Superior literally pushes Julie Andrews’s Maria out into a world of sexual enjoyment, as if it is she who is arranging for Maria and Captain von Trapp to fall in love and then pushing her to seduce him into consummation with the world climb ev’ry mountain. An innocent nun raised in a convent going out and experiencing a mediated world – what could possibly go wrong?

But it is I who am the pervert, not Sister Anna or her superior. I watch the scene where Anna meets her aunt, who is just seeing a man from a one-night stand out, and I think I know where this is going. Indeed, most of the movie is Aunt Wanda trying to get her novice niece to try sex out. In fact, in a poignant scene after Anna has gone back to the convent, Wanda drinks herself into oblivion and moans that her niece has such good hair but wastes it by covering it up. I think the filmmaker knows that the viewers of the film will have dirty minds like mine, and my sense is that what is disruptive about the film is that he plants just enough of these scenes in there to remind us of the old capitalist trope that the fall of the Soviet Union – including the ‘new Poland’ that this film is describing – came from the infusion of American popular culture and its open eroticism in the glasnost of the 1980s.

But what is portrayed is not the 1980s, but the 1960s, and Wanda Gruz turns out to be the ‘Red Wanda’ of 1950s Soviet fame who sentenced a number of ‘enemies of the people’ to their deaths. Her portrayal is not as the repressed communists in anti-communist propaganda who only use sex for political gain (such as in the Bond movies). Red Wanda is a human being, alive with emotions, frustrations, and self-medicating tendencies like sleeping around and drinking hard and chain smoking in jazz clubs where Coltrane is played to hypnotic perfection. This is the communism that I have become more familiar with in reading the texts of self-proclaimed scientific socialists, rich with feeling, pathos, and humanity, completely unlike the way that they are portrayed as soulless bureaucrats engineering the world for social justice. The Polish People’s Republic is alive with the erotic undercurrent of jazz and more than enough consumerism.

Sister Anna, for whom the communists have likely been portrayed by the Catholic Church as mechanistic demons, discovers that this Red Wanda is her aunt – and more than that, as she tells the hitchhiker saxophonist she and her aunt pick up on the way to the town where they are investigating their family history, she learns that her family is Jewish and that her name is not Anna – it’s Ida Lebenstein. The anti-semitism here is pathetically ordinary. People who style themselves as everyday folks in communist Poland turn out to be Catholic, but the secret is that this is after an ethnic cleansing. Once upon a time, Jews were also ordinary folks – ‘good people,’ as one character remarks. Now, in the 1960s, well after the Second World War, they are the other, as the Skibas – the Poles who occupy the Lebenstein family home – reveal when they investigate the family home. They recognize Anna as their own and ask her to bless their child. But Wanda is not only a communist; as the husband protests as they enter the home, ‘No Jews ever lived here.’ A priest from the local church operates with the same dichotomy: she treats Anna as his own because she is a nun, but intimates that Jews, like Anna’s communist Aunt Wanda, are the other.

Popular culture in Ida includes this ordinary anti-semitism, and the oft-cited opposition between Catholicism and communism gets cast into horrifyingly stark relief. The subtext is that the communists were hated not because they were Marxists or Soviets or Russians, but because they were all indiscriminately seen in the popular culture as Jews. The other undercurrent is that Wanda, already self-medicating in the 1950s with booze (as she tells the police officers when she drinks, drives, and runs her car into a ditch), has gotten herself into a position as a judge to exact revenge against the fascists who killed her family by framing them as ‘enemies of the people.’ I can destroy you, she reminds Skiba as he hesitates to tell her where the bodies are buried. The next day, with assurances of immunity given, he takes Anna and Wanda to the forest. Digging up the makeshift grave and then crouching into it in a fetal position, he reveals that while Wanda had left Anna’s parents and her young son with the Skibas for their protection, he had taken them out to the forest and murdered all of them. And why am I not here? Anna asks. The anti-semitic secret is then revealed: Wanda’s boy had been dark and circumcised, but Ida was so small that she could pass, and so he simply took her to the local priest, which is why she was raised in a convent as Anna. Wanda wraps the skull of her little boy in her scarf and walks away. Later, after arranging her family tree, drinking herself into a stupor, and have a last one-night stand, she turns up Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony and jumps out a window to her death, as the final victim of this popular anti-semitism.

Both communism and Catholicism are thus revealed as stupid ideologies covering the deep-seated racial tensions and erotic consumerism of Polish society at that time. When Anna gets back to the convent, she can’t help but laugh at the stupidity of the nuns treating even their eating of dinner as a ritual act where bringing fork from plate to mouth and then back down to plate has to be done in rigid unison. At Wanda’s burial, the adulations for Comrade Wanda’s contributions to the building of a New Poland and the muffled broadcast of ‘The Internationale’ sound so comical now that we know all of Wanda’s secrets. It is these stupidities that finally get Anna to try out an identity as Ida. She puts on Wanda’s stilettos. With fingers practiced in lighting matches to heat the convent and to light candles, she has her first cigarette. She drinks vodka like her aunt from the bottle. She lets her hair down, puts on an evening dress, and goes down to the jazz club, where she allows herself to be seduced by the alto saxophonist, dancing the night away to Coltrane and sleeping with him afterward. At this erotic level, he doesn’t care that she’s told him she’s Jewish; when he found out, he quipped that he had a bit of gypsy in him too, revealing yet another level of European racial formation that the film does not fully explore.

But the film ends by Ida putting back her novice clothes as Sister Anna and walking back to the convent. The night before, she and her lover had had a conversation in bed. He tells her that he has a series of shows in Gdańsk, far from where they are now, over in the shipyards where she has never been. She asks him what they’d do there, and he replies that they’d hang out, and eventually get married, have kids, and live an ordinary life. She leaves him in the morning, going back to her life as a nun.

Here, I think, the secret of the film is finally revealed. There is a strand of Jewish interpretation of the story of Adam and Eve, recounted for example in Nahum Sarna’s Understanding Genesis, that contradicts the popular Western Christian reading. Instead of emphasizing the eating of the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil as the source of original sin by which the world was damned, this particular Jewish telling has it that this is a moment of conscious maturity, that being like gods, the woman and the man are driven out of their state of innocence to know the world so that they can relate to the divine in a mode of maturity. I realize that I must be careful here because Jordan Peterson and I are unfortunately agreed in this narrow slice of our reading of the Genesis text (much as I despise his biological reductionism in his explanation of consciousness, including in his telling of the Genesis story).

But in Anna’s return to the convent after being sent out, I really do see less of a Žižekian critique of Catholic ideology and more of the possibility that Ida is a film with distinctively Jewish overtones set in a Catholic and communist world. The film begins with Anna painting the features on a statue of Jesus Christ. When she returns to the convent the first time, she asks this figure to forgive her as she backs out of taking her vows. It is in the world that she has to reconcile her newly discovered Jewishness with the reality of anti-semitism, the façade of communism, and the popularity of Catholicism. Only through her experience with the erotic does she glimpse the possibility that her vows are not to an institution, but to a person, that which her hands have touched and whose features she painted. Given the choice between sex with a saxophonist that will lead to an ordinary life and a life of prayer where she gives the whole of herself – including her Jewishness – to Jesus Christ, she makes the more intensely erotic decision and goes home – not to a place of innocence, but to a site of intensity.

With Anna’s realization that she can be Ida even in the convent, we discern what popular culture really is. It is that erotic undercurrent that strips away the façades of its institutions. But it is also not to be equated with consumerism, at least not exactly. Anna does not opt for the ordinary life that begins with watching her lover play shows in Gdańsk. If one were to ask those who equate popular culture with the liberal American consumption of eros, that would be her natural choice – to throw off the mask of Sister Anna, fully embrace her identity as Ida, and end up living a normal married life. Anna’s discernment here is profound. Having tasted the fruit of popular culture, she learns that capitalism is as bland as its Catholic and communist counterparts. The real wound is closer to the anti-semitism, the primal division by which ordinary folks determine who is inside of the nation and who can be killed. If there is original sin, it is this racism, the kind against which Wanda self-medicates and ultimately for which she commits suicide, the sort that drove Skiba to murder the Lebensteins, the type that confuses Anna as she becomes increasingly conscious that she is not as much of an insider as others think she is. In her experience of the culture of the people, Anna discovers this wound in herself. Through the erotic experience afforded her by her diving into an encounter with the popular culture outside the convent, she begins to understand it.

Far from being consumeristic in a shallow sense and attached to liberal capitalist structures, the popular culture of a society is a revelation of its erotic core. It is to be investigated, understood, contemplated, and psychoanalyzed. I suspect that my pop psychoanalysis posse knew this all along and were waiting for me to get on board. I am thankful for their patience as my tastes become truly Catholic in the sense that Ida is. Perhaps with my most recent birthday, I really am starting to mature because I have friends who care enough about me to get me to encounter the world as it is, and not as I wish it were.