Why did God allow this to happen? Maybe that’s not the most helpful question to ask post-election. Here’s my response to post-election theodicy.

Recently, a friend asked me this question about the results of the 2024 election:

“Why would a loving God allow this to happen?”

If you’re asking that kind of question, you’re not alone. It’s a question any person of faith who believes in a loving God would ask, knowing what chaos, hardship, horrors, and suffering are on the immediate horizon.

It’s also a question that comes up in the Bible.

- Job famously asked God why he, a good and faithful person, was allowed to endure incomprehensible suffering (Job 3:20-23).

- The book of Psalms contains many complaints about God either not hearing or paying attention or caring about suffering. For example, Psalm 10 begins by asking: “Why, Lord, do you stand far off? Why do you hide yourself in times of trouble?”

- The prophets were constantly shaking their fists at God about the injustice and suffering in the world. The prophet Habakkuk asks, “How long, Lord, must I call for help, but you do not listen?” (Habakkuk 1:2-3).

- Jeremiah demanded to know: “Why does the way of the wicked prosper? Why do all the faithless live at ease?” (Jeremiah 12:1). We echo his enragement as we watch the bulging billionaires preparing to divide the spoils of our democracy while the Christian nationalists plunge us into the terrors of christofascism.

- Even Jesus himself uttered an excruciating cry of theodicy as he suffered through state execution: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46).

Why have you forsaken us?

We did everything we were supposed to do. We kept the faith, did the hard work, built coalitions, got out the vote, and still . . . the fix was in. There were forces at work that were so much more insidious, so much more powerful than we anticipated.

So, Jesus’s words of deep anguish, which are also from Scripture – Psalm 22 to be exact – accurately capture our feeling of abandonment and confusion.

And we know that suffering is inevitable because the incoming administration has promised it. They take utter psychotic, sociopathic pleasure in the suffering of others while they enjoy the protection that their wealth, power, and weapons afford them. In theological language, we call this sin, and it’s sin of the worst kind.

Of course, then, it’s natural to ask: Why did God allow this to happen?

So, it’s time for a post-election reflection on theodicy.

Theodicy is a theological term that wrestles with the paradox of three premises:

God is good.

God is all-powerful.

There is evil and suffering in the world.

If God is good, why would God allow evil? Perhaps God is not good after all. Or maybe God is not all-powerful.

Because if God is all-powerful, why would God allow evil?

You can see how these kinds of questions can tie a person into theological knots.

How people have tried to untie these theological knots would constitute a whole seminary course. But for brevity’s sake, there are four common theodicy explanations.

Maybe God is punishing us.

Or testing us.

Maybe God is trying to teach us a lesson.

Or maybe this is a roundabout way of God fixing things that we just don’t understand yet.

Perhaps.

But any of these explanations followed through to their logical conclusion deposit us right back at a refutation of the first principle: God is good.

Let’s break them down.

Punishing? No.

God is not punishing us with these election results. Because a good, compassionate God would not inflict suffering on innocent people just to get back at the bad people.

Some may argue that another biblical catastrophic event – the Great Flood in Genesis – was God’s punishment of humanity’s wickedness. That is certainly is one way to frame it, and the biblical writer uses that framing.

But at its most basic level, the ancient flood – and the coming flood of evil we’re facing – is simply the consequence of humans violating Creation and God’s ethic of care, equity, generosity, and liberation from oppression.

Asserting that the election results are divine punishment constitutes a kind of collateral-damage theology that makes God no better than a totalitarian leader flattening all of Gaza and killing children with the rationalization that genocide is necessary to root out a terrorist network.

So, no. A good, compassionate God is not using this election outcome to punish us.

Testing us? No.

God is not testing us with this election aftermath. Testing means that we either pass or fail. Sure, some of us will grow better and stronger. But others will grow weaker and die.

This is the demented social Darwinism used in Nazi ideology which argues for “survival of the fittest.” It means that the old, weak, sick, non-Aryan, non-heterosexual cisgendered, non-hypermasculine, and non-wealthy must be eliminated. Unless they can be used in some way to serve the elite class. In which case they are kept in the bondage of subsistence and misery until they are no longer useful.

So, no. A good, compassionate God is not using this election outcome to test us.

Teaching us a lesson? No.

God isn’t teaching us a lesson through this election. Are there things we need to learn? Certainly. But if this election result is how God chose to do it, that’s a real problem.

Because this would mean that God designed a cosmic curriculum for us that included a global network of neo-colonial, racist, female-hating, propaganda-spewing, oligarchical tech bros hell-bent on destroying the world and remaking it in their own image.

So, no, a loving, compassionate God would not do any of this just to teach us a lesson.

Mysteriously using this crisis to fix things? No.

God breaking the world in order fix it is no different that the self-idolizing Elon Musk, Curtis Yarvin, and others in their amoral circle of oligarchs insisting that the infrastructures of government and society must be smashed and dismantled in order to usher in a new age of noocracy ruling over feudal techno-states where we’re either slaves to their wealth accumulation or fodder for concentration camps, ovens, and mass graves.

We can do without that kind of idolatrous, malignant narcissistic fixing, thank you very much.

So, no, a loving compassionate God is not mysteriously using the election results to fix the world.

Then, why do people cling to these false theodicies?

Problematic theological claims are often thrown around when “bad things” happen.

These theological explanations are humanity’s attempt to make sense of something that is horrific and painful. But too often these explanations end up rationalizing a problematic theology.

There are some key questions to ask whenever we hear these questionable theological claims (or we are tempted to make them ourselves).

Who might be hurt by this theological explanation?

Who stands to profit from it?

Is there a more helpful and nuanced way to approach this problem of theodicy?

A long time coming

Brian McClaren observes in his book, Life After Doom: Wisdom and Courage for a World Falling Apart (my new companion for this journey): “Things have been worse than we thought, and this moment has been decades in the making.”

You probably have known this at some level for a long time. And the results of the election have only confirmed your worst fears. The systemic sin all around us is reaching a dangerous peak.

But is all of this God’s fault?

Ten years ago, Lutheran theologian Peter Marty wrote about the problem of theodicy and its different explanations.

God gets blamed for all kinds of outlandish things, mostly because we don’t like to feel out of control in a chaotic universe. If we position God to assume the blame or credit for an inexplicable situation, suddenly it sounds more reasonable. Many people don’t like the idea of no one being responsible for a perplexing event.

Thus, God becomes the handy arranger when one needs a cause for that flat tire in the desert, or for that stillborn child who had been the sparkle in a hope-filled couple’s eyes. (The Lutheran, January 2014, pg. 3)

Or, for that matter, an election that will lead to national christofascism and possibly global annihilation.

God’s dereliction of duty?

Marty continues:

Some believers will resort to language of God allowing certain events, even if God did not cause them.

But that theological reasoning presents huge problems, usually indicting rather than complimenting God. If my child drowns in a swimming accident and you try to comfort me by suggesting God allowed the drowning for a reason, that means God failed me. It would be akin to having a strong lifeguard, with all the equipment and rescue skill in the world, just standing by to watch my child go down. That would be gross dereliction of duty.

What, then? Where is God in all of this?

Isn’t God in control?

Well, that depends on what we mean when we say, “God is in control.”

Do we mean that God changes the traffic light to green when I suddenly approach an intersection? (Which is what a family member of mine believed, and always thanked Jesus for his intervening hand.)

Do we mean that when bad things happen, God is in control, so we must find a way to understand why God would do such a thing? (Hence the fallacies of “God punishing us” or “God teaching us a lesson.”)

Or do we mean that even when the world seems out of control, we know that our ultimate fate is in God’s loving hands, and so this belief engenders trust and faith?

That’s a step in the right direction. But a feeling of trust and faith in the face of what is to come is not enough. Because that can lead to quietism fed by an ill-informed eschatology and pacifying hope in the hereafter. [See: Apocalypse When?: A Guide to Interpreting and Preaching Apocalyptic Texts (Wipf & Stock, 2020).]

Because if we stop at a comfortable theological resolution, it gives us an excuse for not taking action.

Any theological claim that leads to complacency, despair, logic-acrobatics, or is used merely as a place holder when we can’t make sense of things, simply is not helpful.

Meaning, not causation

Yes, we’re trying to understand what all of this means because we’re struggling to understand what happened with this election and to make sense of what is utterly and despondently baffling.

But as my theological colleague and dear friend Emily Askew once told students in a class we co-taught on theology and sermons, “Meaning is not causation. We are meaning-making creatures, and we can create meaning from some really difficult circumstances. But just because we find meaning in these circumstances does NOT mean that that was the intention. We confuse our meaning-making with God’s will, or God’s intention. Maybe the two do coincide, but we can’t know that.”

In other words, if you, personally, are discerning a lesson in all of this, or feeling corrected or convicted, or that you’re being strengthened, this is all to the good.

But if the questions are tying you up in knots, just stop. And for God’s sake, don’t push problematic theodicy-resolution on others because it can lead to self-delusion, cause unintentional harm, or place blame a deity who is not at fault.

Even worse, our theodical displacement can be a distraction from the work that needs to be done.

The fact is that humans often blame God for problems that they themselves cause or are at least share some responsibility for — whether its individual sin or collective and systemic sin. Not that God’s shoulders aren’t broad enough to deal with misplaced blame or anger. But theodical displacement can distract or derail us from dealing with the problems that we can address and work on solving.

So, then, where does that leave us?

We are left with three possibilities.

One possibility is that there is no benevolent God.

This is the belief of Christian nationalists. All the qualities and teachings of Jesus – grace, compassion, justice, equity, forgiveness, distributed communal power – are what they reject, mock, and trample.

Theirs is akin to the violent mythology of ancient Babylon where the world arises from a cosmic war among the gods and human beings are created from the blood of a murdered god. In the myth of Tiamat, the only purpose of humanity is to relieve the deities of their labor and serve as slaves.

This is exactly the kind of world that the Musks and Thiels and Vances and Yarvins are designing and poised to implement. Because they believe themselves to be gods.

Another possibility is that there is no God at all.

While it’s tempting to just abandon the notion of God altogether, I, for one, am not willing to cede the spiritual space to this position.

Because if we say there is no God, then those who assert the violent, hierarchical, hyper-toxic-masculine god will be given all that psycho-spiritual territory within human consciousness.

We can’t let that happen.

They already claim and control so much material, social, monetary, technological, and human capital.

As for me, I will not allow them to claim and control my inner theological convictions.

I will not concede the theological high ground.

This means that we have to recommit to the first premise: a benevolent, loving God.

We must reaffirm our relationship with the divine character of love which, in fact, requires that the ethic of love to be applied by humanity to each other and to God’s Creation.

This is not a namby-pamby, or pie-in-the-sky-by-and-by, or “Jesus is my boyfriend,” or “Jesus is my teddy bear” kind of love.

Nor is this a “superhero” love.

We may wish for a Big Daddy in the Sky who will swoop in and save us. Or who will magically intervene to make people do the right thing.

But we do not have a “puppet God” who can be controlled by humans. Nor do we have a “puppet master God” who is controlling OUR strings with the entire world merely the set piece of a divinely-demented play.

What is missing from both images is the principle of RELATIONSHIP. God chose to be in relationship with us, as we learn in all of the Gospels and the New Testament letters, especially in Philippians 2:1-18. And that relationship is infused with a fierce, active love that both gives you space to grieve what has happened with this election and then says, “Okay, now back to work.”

It is a love that is crucified by sin but resurrected by something the human rulers cannot understand: resolute, determined, scarred, indefatigable love.

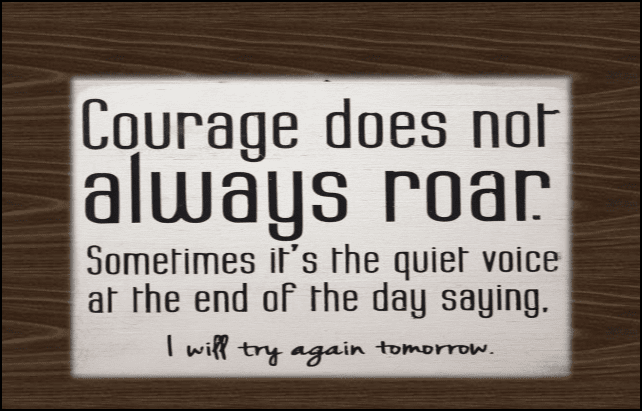

So I say to you as compassionately as I can: take the time to grieve. But don’t blame God for this. Remember that God is love, and then get back to work.

It will require all of us, our resources, our connections, our determination, and our fortitude to not just resist but actively throw a wrench into the machine of destruction that is being unleashed on us.

If you want to know where God is, study the history of oppressed peoples who drew on their faith to survive, support each other, and organize for change. Especially the Black freedom movement in America. As Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. said:

“Those who love peace must learn to organize as effectively as those who love war.”

Attend trainings by organizations such as Waging Nonviolence, Working Families Party and SURJ (Showing Up for Racial Justice). While they are not religious, Christians intent on putting God’s love into action can learn a great deal from them.

You can also connect to local action groups that are gearing up to protect immigrants, LGBTQIA youth and adults, Muslims, Blacks, women, and the environment.

Also, there are many Christian organizations who are already on the ground, ready to put divine love into action for safeguarding the vulnerable and countering the christofascist oligarchy. The Poor People’s Campaign, Christians Against Christian Nationalism, Faithful America, Vote Common Good, Faith in Public Life, and Third Act Faith are all excellent organizations that can support you as you commit to stepping up your faith-in-action.

And if you are a clergy person who is looking to connect with other Christian leaders in this work of resisting and disrupting Christian nationalism, check out the Clergy Emergency League, a group I co-founded in 2020.

Above all, do not let your theological conundrums lead you to defeat, compliance, or surrender.

This is exactly what authoritarians want. As Rebecca Solnit writes in this excellent article for The Guardian, “We do not know what will happen. But we can know who we can commit to be in the face of what happens. That is a strong beginning. The fact that we cannot save everything does not mean we cannot save anything, and everything we can save is worth saving.”

So, let go of the question, why did God let this happen. Instead, ask: Who and what does God want me to help save?

And then get to work!

I am indebted to theologian Catherine Keller’s article about theodicy and responses to the Covid crisis, which you can read here: https://medium.com/@drewtheological/a-letter-from-catherine-keller-1930029c4914

Read also:

4 Faithful Post-Election Messages for Clergy & Congregations

Fill Your Lamps, Church – Let’s Be Ready! Post-election Sermon

Clergy: Prepare for Post-Election Season in Mind, Body & Spirit

3 New Testament Messages for Resisting Autocracy

3 Old Testament Passages about the Tyranny of Kings

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade is the Associate Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching and Social Issues: Tools and Tactics for Empowering Your Prophetic Voice (Rowman & Littlefield, 2024), Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is the co-editor of Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). Her book, Introduction to Preaching: Scripture, Theology, and Sermon Preparation, was co-authored with Jerry L. Sumney and Emily Askew (Rowman & Littlefield, 2023).