Here are 8 signs and red flags that a pastor might be preaching Christian nationalism – either explicitly or implicitly.

According to a 2023 study by the Public Religion Research Institute and Brookings, nearly a quarter of Americans either sympathize with the tenets of Christian nationalism or take part in direct actions (often intimidating or violent) to further the movement. It’s likely, then, that there is a commensurate number of U.S. clergy who are either actively preaching Christian nationalist messages or giving tacit support through coded language.

How can you tell if your pastor is preaching Christian nationalist messages?

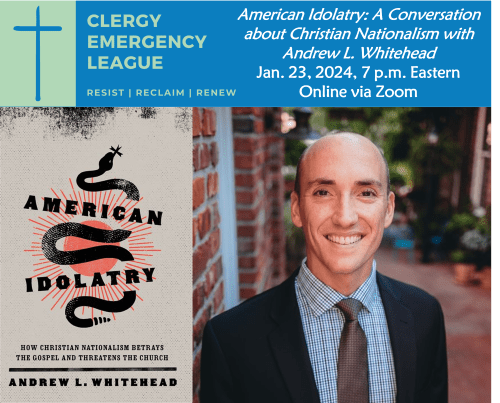

In this article, I’ll draw on Andrew L. Whitehead’s book, American Idolatry: How Christian Nationalism Betrays the Gospel and Threatens the Church to help identify Christian nationalist rhetoric you might hear in a sermon.

[For my full review of American Idolatry, click here.]

Who is Andrew L. Whitehead?

Andrew L. Whitehead is a sociologist who studies religion and American culture at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. He was also raised in the evangelical church and has an insider’s view on the ways in which that branch of Christianity in the U.S. has fused itself with a conservative political agenda. His book, Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States, coauthored with Samuel L. Perry, won the 2021 Distinguished Book Award from the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion.

In American Idolatry, Whitehead issues a profound and indisputable warning about the dangers of Christian nationalism and the harm that it’s causing to the church and those who suffer from the movement’s hold over the nation. While he uses data and scholarly research to verify this danger and harm, Whitehead’s goal in this book is to counter Christian nationalist beliefs with an appeal to historical Christian teachings based on the Bible and the life of Jesus.

Defining Christian nationalism

According to Whitehead, Christian nationalism is “a cultural framework asserting that all civic life in the United States should be organized according to a particular form of conservative Christianity” (xii). Christian nationalism is marked by the way that it privileges the experiences and identity of White people while also aligning with a conservative political ideology.

This fusion of white identity politics with conservative Christianity leads to citizens who “demand and defend [their] own rights at the expense of others, not alongside them,” (48). At their worst, these attitudes result in harassment, threats, and violence against anyone deemed as an outsider or enemy. Such behavior is the exact opposite of what Christ taught.

Preaching Christian nationalism

As a seminary professor who teaches preaching and worship, I appreciated the way Whitehead drew attention to the messages that Christian nationalist preachers convey to their congregants. As Whitehead explains, “The sermon is the focal point of most Protestant worship services in the United States. Therefore, its content is important for shaping the lives and imaginations of the congregants and for attracting and drawing in new congregants” (40).

Sometimes those messages are explicit and sometimes they’re coded. But even coded language can sustain Christian nationalism by promoting its cultural framework. In any case, it’s important to know what those messages are and how they might show up in a sermon.

8 signs and red flags that might indicate your preacher is supporting Christian nationalism

1 – The preacher emphasizes personal salvation over collective liberation and social justice

If you hear messages from the pulpit that continually emphasize individual sins over our collective enslavement to sinful systems, it might be laying the groundwork for Christian nationalism. This is because Christian nationalism is hyper-focused on the future of souls rather than the systemic conditions of injustice.

Whitehead suggests trying this: listen to the sermon from the perspective of someone who suffered under slavery or who has been forced from their homeland. If the sermon only points to future salvation and says nothing about current suffering, it’s making an implicit theological claim that God does not care about what is happening to people right now (11).

By extension, then, the preacher is giving the church a pass from having to care about suffering as well. And if we can theologically justify suffering, we can rationalize our refusal to ease that suffering. It gets Christians off the hook in advocating for policies that improve the lives of people in the here and now.

2 – The preacher infuses the Founding Fathers and Constitution with mythic Christian significance

Christian nationalists make factually incorrect statements that the founders of the United States were all fundamentalist Christians and that we need to return to being a “Christian nation.” “Religious and political leaders push this narrative because it establishes a foundation from which they can argue that their particular values should take precedence,” Whitehead explains (45).

This fallacious myth is easily debunked with even a cursory reading of U.S. history during the colonial period. “If the founding period was particularly Christian,” asks Whitehead, “why did it include the genocide of native peoples and the enslavement of Africans?” (45). If you hear messages from the pulpit rationalizing this horrific history, you’ll know that the agenda of Christian nationalism is at work.

3 – The sermons revolve around “biblical values”

Whitehead explains that Christian nationalist preachers tend to limit their focus on social issues that have to do with things like traditional marriage, opposition to abortion, and sexual morality (41). While individual morality-policing is bad enough, what’s more worrisome are exhortations that “Christians should gain access to more levers of power to ensure that the nation faithfully embodies these moral claims,” Whitehead says (41).

The fact is that truly biblical values also include concern and care for those oppressed by poverty, migrants and foreigners, and vulnerable children. So if your pastor is not preaching on themes that take on issues such as wealth inequality, racial injustice, or reforming the criminal justice system, they are not taking seriously the entirety of Christian teachings and the biblical witness.

4 – The preacher pits “us” against “them”

If you hear sermons that draw lines between who is in and who’s out so as to demonize people of a different political ideology, race, religion, or nationality, it is likely that your preacher is leaning toward Christian nationalism. Such sermons spend a lot of time defining who “we” are not, rather than making definitive claims about who “we” are (43).

What the preacher will often claim under the us v. them rubric is that the U.S. is a Christian nation “chosen by God.” Such language can be used to support a fascist agenda that rationalizes claiming power for “our” side and even using violence against those who oppose “us.”

5 – The sermons turn Jesus into your boyfriend, your mascot, or your cultural warrior

If you hear language about Jesus that domesticates him or uses him to justify a culture war, this is a red flag. You can hear “Jesus is my boyfriend” language in contemporary Christian songs and in some sermons. Certainly, Jesus preached love, but when the rhetoric about this love takes on a personal, even romantic connotation, it waters down Christ’s calls for justice and his actions in confronting the sinful systems of his time.

Whitehead adds that when it comes to those outside Christianity, as well as those who have left, what they see is the church treating Jesus as a “mascot, useful only for baptizing our efforts to (re)make American society as we see fit by protecting and increasing our power and privilege,” (19).

This “mascot” can also morph into a cultural warrior, as seen in some of the imagery around Jesus used by right-wing extremist groups and social media memes. All of this is in alignment with Christian nationalism.

6 – The preacher insinuates threats from external foes and stokes fear

Whitehead notes that “Because white Christian nationalism seeks power and privilege, fears of losing unfettered access to cultural and political power engender narratives of persecution. These narratives center on how ‘they’ are taking away what is rightfully ‘ours’” (42).

If you hear your preacher use words like “persecution” and “attack” while simultaneously pointing to the “good ole days” when Christianity was the cultural center of the nation, beware (42-44). Invoking nostalgia while stoking grievances or fears of loss due to others is a powerful motivator for Christian nationalists.

7 – Listen for what the preacher leaves out or labels a “leftist agenda”

Does the preacher lambast other Christians for caring about racial inequality, an unfair economic system, an unequal justice system, or welcoming immigrants? Do they label these things as part of a “leftist agenda?” Or do they simply ignore such topics?

If the word “justice” (which is found repeatedly throughout the Bible) is considered a dirty word in your church, your pastor might support a Christian nationalist ideology.

8 – The sermons glorify or rationalize violence

Notice what kinds of biblical passages your pastor uses. Do you hear stories about battles against Israel’s enemies that imply that the use of violence is permissible to “defend the faith” or fulfill God’s will? (109). Do you hear the preacher talk about Jesus “fighting” for you? Does the preacher noticeably avoid Jesus’s calls to nonviolence (e.g., “Those who live by the sword will die by the sword” [Matt. 26:52])?

Also note: does your pastor advocate for the use of firearms to defend the church? Or carry a gun in church? In worship?

These are all indications that your pastor might be preaching Christian nationalism.

Whitehead notes that “it can be a small step between fighting spiritual battles to defend your family and religious community and fighting physical battles to do the same,” (109). Using biblical stories of physical battles and imagery that glorifies war as lessons for spiritual battle is suspect at best and coded language sanctifying violence at worst. “No matter the scale,” says Whitehead, “Christian nationalism provides the theological justification for violence toward enemies” (107).

Coded language

The way such coded language is meant to be heard is: “Just like David, Moses, Gideon, and other Israelites, I might have to violently defend my life or the lives of my family members from threats. Similarly, I may have to engage in or support collective violence to counter threats to our way of life (Christianity) arising from those who want to destroy it (non-Christian nations and peoples)” (109).

If this language, imagery, and coded messaging around violence concerns you, seek out a church where the pastor emphasizes messages of peace and nonviolent civil disobedience to effect change in society. From these preachers, you should hear that “God beat the power of human empire not with a sword but with the power of the Resurrection,” as Lisa Sharon Harper says (The Very Good Gospel: How Everything Wrong Can be Made Right (Colorado Springs: WaterBrook, 2016], 174).

Whitehead adds, “Jesus’s power – and by extension ours – lies not in exerting power over others through violence but in giving our lives, trusting in the power of God to bring new life out of death” (127).

What if my preacher doesn’t talk about political issues at all? (Hint: silence = complicity)

In a longitudinal study my team and I have been conducting since 2017, we’ve been tracking the attitudes and opinions of U.S. preachers about ministry and social issues. In the three survey waves, there was a segment of the respondents who say they refuse to address social issues in their preaching.

Preachers give various reasons for this avoidance. Some fear dividing the congregation. Others believe that they should stay out of politics and focus instead on winning souls for Christ. Still others believe it is more important to focus on individual morality and generic themes such as forgiveness, grace, and faith without any concretization in contemporary issues.

But if your pastor isn’t saying anything about social justice issues, they are still communicating something about the church’s role in the public square.

At the very least, their silence is giving de facto consent to the harm being done to people and the planet. And they may be doing it with a rationalization that does not hold up under scrutiny.

So even if your pastor is not explicitly preaching themes of Christian nationalism, if they’re also not speaking against those themes, then they are implicitly communicating one of three things. Either they have no problem with what is happening. Or they actually agree with it. Or they are too worried about the pushback if they preach against Christian nationalism.

Ask yourself this:

“After hearing a message, consider whether the speaker was encouraging you to embrace love and liberation or power and control,” Whitehead advises (42). If you hear the former, your preacher is probably sharing gospel-centered messages focusing on the teachings of Jesus and the prophets. But if you hear the latter, your preacher might support a Christian nationalist ideology.

If you are uncomfortable with this, it’s time to find a different church with a minister who strives to preach and live out the grace-filled, justice-oriented gospel of Jesus Christ. But if you are completely at ease with and supportive of this ideology? Well, read Andrew Whitehead’s book, American Idolatry, and see if it might change your thinking and your heart.

What if I’m the preacher and I’m worried that I might be inadvertently conveying Christian nationalist messaging?

Whitehead encourages those who preach to “invite others to help you review your recent messages and determine whether you tend to embrace a hermeneutic of fear, control, or even withdrawal” (186).

If you see signs of these Christian nationalist tactics in your own sermons, “consider where and how you can begin to listen to and learn from the biblical interpretation of those marginalized by power” (186). Reading biblical scholars who come from perspectives such as Latino/a, Asian, disabled, queer, womanist, or ecological hermeneutics is a great way to expand your interpretive palate and help your congregation hear different points of view.

Teach your congregation about Christian nationalism

Also important is making a commitment to “faithfully socialize your congregation into an expression of the Christian faith that is incompatible with white Christian nationalism, one that equips them to recognize and question the theologies that undergird it,” Whitehead says (186). When we do this, we can live into Christ’s example of “service and sacrifice for others, resulting in abundant life for all, rather than control and domination of others (see Col. 2:6-15; Eph. 6:12)” (190).

American Idolatry: How Christian Nationalism Betrays the Gospel and Threatens the Church by Andrew L. Whitehead (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2023) is available from Baker Publishing Group in hardcover, as an ebook, and as an audiobook read by the author.

Read also:

American Idolatry by Andrew L. Whitehead: Book Review

Countering the Temptations of Christian Nationalism: Matthew 4:1-11

Book Review: For the Facing of this Hour: Preaching that Resists White Christian Nationalism

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade is the Associate Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. She is the co-founder of the Clergy Emergency League. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching and Social Issues: Tools and Tactics for Empowering Your Prophetic Voice (Rowman & Littlefield, 2024), Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is the co-editor of Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). And she co-authored Introduction to Preaching: Scripture, Theology, and Sermon Preparation, with Jerry L. Sumney and Emily Askew (Rowman & Littlefield, 2023).