Good Omens has this seminary professor hooked. It’s an antidote to toxic Christian apocalyptic fiction and a poignant reminder about the importance of kindness in an absurd world.

Good Omens is a fantasy comedy series based on the book by Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett. Both Seasons One and Two of the British series (available on Amazon Prime) are comprised of six episodes that follow the adventures of the angel Aziraphale (Michael Sheen) and the demon Crowley (David Tennant) in their unlikely yet inevitable friendship across the vast span of time to prevent the end of the world.

Spoiler level: medium.

How Good Omens got my attention

The trailer for the first season of Good Omens piqued my curiosity because it’s based on a book co-written by Neil Gaiman whose The Ocean at the End of the Lane still sweetly haunts my memory. Gaiman tackles cosmological and philosophical themes with stunning imagination through endearing characters and riveting, ingenious storylines grounded in the everyday-ness of mortal existence. Plus, his sense of humor combined with tenderness toward his characters draws readers irresistibly into his fantastical worlds.

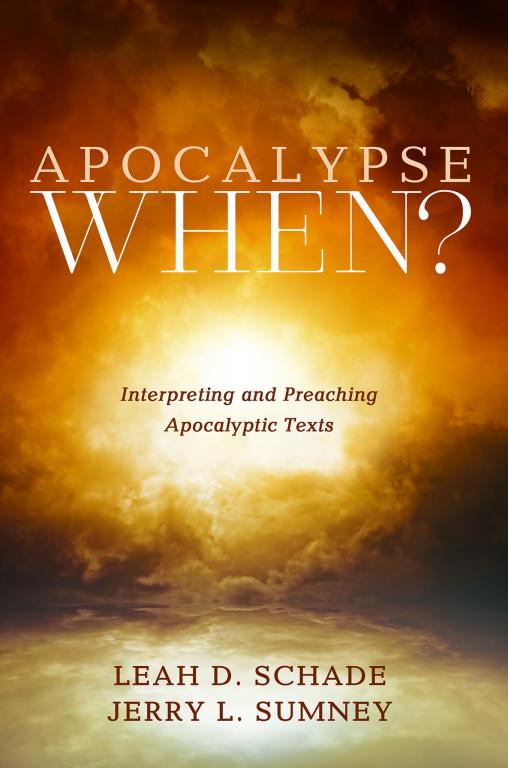

Another reason for my interest in Good Omens is because I co-wrote a book called Apocalypse When: Interpreting and Preaching Apocalyptic Texts that contains a section discussing the ways in which popular culture portrays the end times. So, I was keen to see how this quirky, ambitious series would handle Judeo-Christian imagery around angels and demons, heaven and hell, cosmology and eschatology.

There is much to say about Good Omens that I’ll be exploring in future posts. For this first one, however, I’ll focus on just two aspects of the series: its treatment of biblical stories and the way it flips the script on the genre of Christian apocalyptic fiction.

Good Omens plays with the absurdity of biblical narratives

Here is one thing that biblical literalists miss about the Bible.

There are stories in Scripture that are absurd. And they’re absurd on purpose. Why? Because they’re meant to get us thinking about who we understand ourselves to be in relation to each other, to God, and to the unpredictable world in which we live. And then to think about how we will choose to act.

The Bible takes as its premise that God is a benevolent Creator who wants human beings to adhere to moral and ethical codes that will help them navigate conflict, care for the vulnerable, and live in community together.

Interestingly, however, the Bible also portrays God as having a range of human emotions – anger, joy, arrogance, petulance, parental care, and righteous judgment, to name a few. At the same time, there is a mystery to the Almighty that is beyond human understanding that often leaves us baffled. In Good Omens, the word for that mystery is ineffable. God has an Ineffable Plan.

As Gaiman puts it in the book, “God does not play dice with the universe; He plays an ineffable game of His own devising, which might be compared, from the perspective of any of the other plays, to being involved in an obscure and complex version of poker in a pitch-dark room, with blank cards, for infinite stakes, with a Dealer who won’t tell you the rules, and who smiles all the time” (10).

In other words, there is an element of absurdity to the notion of God and to the ways God is described in the Judeo-Christian Scriptures.

Whether it’s the fall-out from the consciousness of good and evil in the Garden of Eden, or the trials of Job, or the killing of Jesus (all of which are touched on in Good Omens), there is something absurd about these stories that leave us scratching our heads. How do we make sense of things that don’t appear to make any sense? And what choices will we make in the face of this absurdity?

Good Omens sublimely captures this absurdity in the dialectic between its two main characters, Aziraphale, the good angel, and Crowley, the fallen angel turned demon. (Although Crowley insists he did not “fall,” but merely “sauntered vaguely downwards.”)

Aziraphale and Crowley in Eden

In the first scene of episode 1, season 1, Aziraphale and Crowley (called Crawley at the time, because he is the snake who tempts Eve and Adam) discuss the seeming absurdity of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. If the humans weren’t to touch it, why put it there at all? What’s so wrong about knowing the difference between good and evil anyway? And why cast them out for a first offense?

These are questions Crowley poses as the two of them stand atop the wall surrounding Eden watching the first humans walk out into the desert. Those kinds of questions are what got him in trouble in the first place. He was cast out of Heaven; now the humans are cast out of Paradise.

Sweetly naïve Aziraphale is visibly nervous by his line of questioning. “Best not to speculate,” he concludes. “You can’t second-guess ineffability, I always say. It’s all part of the Great Plan. It’s not for us to understand. It’s ineffable. . . It is beyond understanding and incapable of being put into words.”

In the meantime, there is another burning question. Literally burning, because Aziraphale no longer has his flaming sword meant defend the Tree of Life. What happened to it?

Turns out he made the choice to give his flaming sword to the humans for protection. Moved with compassion at their plight, he couldn’t bear to send them out of the Garden without any assistance, so he gave away his heavenly weapon. He worries if this was the right thing to do.

Crowley responds, “I’m not sure it’s actually possible for you to do evil. You’re an angel.”

He goes on to muse that perhaps tempting the humans with the apple was actually the right thing to do. “Funny if I did the good thing and you did the bad one, eh?” he asks, nudging Aziraphale, who rejects such a notion. He simply cannot wrap his mind around the paradox.

This conversation foreshadows a theme that will surface often throughout the series: the nature of good and evil. Who gets to decide which is which? And under what circumstances? What happens if the right thing is done for the wrong reason? Or the wrong thing is done for the right reason? Is it the intention or the outcome that makes an action right or wrong? And how do these choices shape us as individuals, in our relationships, and in the larger scheme of things?

As the world’s first rain begins to fall, the scene ends with Aziraphale extending his wing over the darkly-cloaked Crowley who moves just a step closer to his white-robed companion. Kindness in the face of an absurd world. Friendship extended in tentative hope, light as a feather in an angel’s wing.

This exchange sets the stage for their relationship that develops throughout the series. Over the next 6,000 years, they bump into each other at key points of absurdity in human history – Noah’s Ark, the French Revolution, World War II – while figuring out how they will relate to each other, to the humans they are charged with either defending or assailing, and to their respective “sides” – Heaven and Hell. All while trying to make a way for themselves under, around, and even straight through the Ineffable Plan that may (or may not) involve Armageddon and the end of the world.

About that business of ending the world . . .

As a child in the late 70s, I was invited by members of my extended family to a church “movie night.” The film turned out to be a terrifying portrayal of the end of days and Jesus’ return, with eerie imagery of celestial events and mass chaos on Earth. After the movie, when they asked what I thought, I told them how scared it had left me. They nodded approvingly and insisted that the events depicted were based on the Bible and that everyone should be afraid of Jesus’ return.

That message of apocalyptic fear was reinforced by a book they gave me: Frank Peretti’s 1986 best-seller This Present Darkness. Emblematic of the Christian Right’s culture wars, the book is a realistic-fictional tale in which the human characters’ experiences parallel intense spiritual warfare unfolding between angels and demons. The residents of a small town grapple for control of a local college that threatens to become the locus of evil through, you know, education. Towards the story’s conclusion, the collective prayers of the faithful in the town empower the angels to vanquish the demonic forces and thwart their plans to teach malevolent things like, say, tolerance and acceptance.

For weeks after reading the book, I was on the lookout for signs of the angel-demon battle raging all around me just beyond the vision of my mortal eyes. It sounds silly now, but I was fifteen at the time and the book got its hooks into my imagination in a dangerous way. It took several deconstructing conversations with my parents (who are Lutheran, one of whom grew up in a strict fundamentalist family) and the pastors of our church to unravel and unpack what the book had done to my brain.

You see, Christian apocalyptic fiction is designed to instill an “us” versus “them” mentality and force readers to accept a narrow black-and-white version of Truth.

The Devil and his minions cleverly disguise themselves in all manner of ways in order to draw people away from faith in Jesus Christ. What appears to be good is, in fact, evil. Any shades of grey, any nuance, any moral complexity is anathema to be rejected lest one lose their immortal soul.

As I made my way through college and eventually to seminary to become an ordained Lutheran pastor and then a seminary professor, I watched Christian apocalyptic fiction move into the cultural mainstream with the Left Behind series by Tim LeHaye and Jerry Jenkins. I’ve spent a significant part of my ministry and teaching helping parishioners and students to deconstruct the harmful theology of conservative Christian apocalypticism.

I wish I had known about Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch

Gaiman and Pratchett’s 1990 book would have been a helpful antidote for my struggle against toxic Christian apocalypticism had I known about it at the time.

The authors playfully turn the genre of Christian apocalyptic fiction on its head. In Good Omens, angels and demons are blunderingly inept in their tasks. They are cheeky with each other and with their bosses in their respective hierarchies. And they are confounded by humanity’s ability to harm each other in ways far beyond any scheme a demon can devise. (Although Crowley is given credit for inventing the selfie, so there’s that.)

When the advent of Armageddon is finally announced, the demons can’t even pull it off without mucking it up. And anytime the Archangels come to Earth, they are too self-absorbed, arrogant, or clueless to realize they are being played, poked fun at, and preempted by a celestial odd couple hellbent/heaven-bent on preventing the harm of innocent people and the end to the world.

What Good Omens has is what’s lacking in all conservative Christian theology and its pop culture artifacts – a sense of humor.

Right-wing Christian ideology takes itself so seriously. It cannot tolerate the kind of teasing humor we see in Good Omens. It’s the ability to wryly look at oneself and the absurdity of the universe and simply laugh. Sometimes it’s rueful laughter, sometimes defiant, and sometimes bubblingly joyful (those are the times when Aziraphale and Crowley are their freest, most relaxed selves). But whatever the form, it’s laughter that holds the tension of opposites without becoming subsumed in sorrow or blown apart in fury.

In contrast, fundamentalist Christianity swings between holier-than-thou platitudinous piety and raging, destructive, violent anger. There is no place for moral complexity or ethical conundrums. And it is precisely between these two dichotomous poles that our protagonists, Aziraphale and Crowley, find themselves.

Each of them is at their worst when they most closely adhere to their “side.” Aziraphale can be alarmingly dutiful and devout, often oblivious to the harm that results from his insistence on following the rules and judging things to be either “right” or “wrong.” For his part, Crowley’s reckless, intense passion, hedonism, and proclivity for mischief can literally burn the world – and himself.

But when Aziraphale and Crowley are in relationship with each other, something happens.

We learn in Season 2 that their first encounter wasn’t actually atop Eden’s wall. It was In The Beginning, even before the Beginning. Aziraphale comes upon Crowley – who is still an angel at this point — just as he’s about to carry out God’s plans for the let-there-be-light-show of the universe.

A word here about the incredible acting of both Michael Sheen and David Tennant. Tennant’s child-like wonder at the “star factory” is radiant as he delights in the birth of an infinite cosmos. Meanwhile Sheen’s cherubic happiness is as much in what has been created as with the one who cranked it all up. When Crowley says, “Look, at you, you’re gorgeous!” Sheen’s face blushes with flattery before he realizes that those words were meant for the newly-created universe. (Or were they?)

But this brief moment of joy dampens when Aziraphale reveals that God intends all of this to last a mere 6,000 years.

Crowley is nonplussed. “What’s the point in creating an infinite universe with trillions of star systems if you’re only gonna let it run for a few thousand years? The engine won’t have properly warmed up by then.”

As he will later do on Eden’s wall, Aziraphale voices his caution and concern about questioning the Almighty. “I’d hate to see you getting into any trouble,” he frets.

Crowley casually dismisses his concern with another foreshadowing question: “How much trouble can I get in for just asking a few questions?”

Then, as a star shower begins to fall, Crowley spreads a wing over Aziraphale to shield him. Just as Aziraphale will later shield him from the world’s first rainstorm on Earth.

Once again, it is a moment of beautiful symmetry, friendship, and tenderness in the face of absurdity.

Shades of grey in a black-and-white world

As we watch their friendship develop over the next 6,000 years (and the course of twelve episodes), we see how each of them “blurs the edges” between their two sides, as Crowley puts it. But it’s more than just creating “shades of grey” as Aziraphale describes it. They are learning about themselves apart from the dictates of their respective camps.

In fact, they are learning what it is to be human. Heaven and Hell’s Pinocchio puppets become real boys, and this gets them into real trouble.

Both the Above and Below accuse them of “going native,” enjoying too much of Earth and human pleasure. And neither side can brook the notion of the two of them fraternizing with “the enemy.” Their friendship could mean the end of each other’s existence. Yet their irresistible draw toward each other is what makes their existence not only meaningful, but essential. And it is what leads them to prevent Armageddon and forestall The End.

The cleverness with which they pull off their plan is something you’ll need to watch for yourself. No spoiler here for the ending of Season 1.

The angels have their work cut out for them

But as you watch (or re-watch) the series, you might think about your own choices, and our collective choices, as humanity faces an actual Armageddon-like threat of climate and ecological collapse. We are unraveling the very fabric of life, destroying each other and other lifeforms with a ferocity that would make even the demons go wide-eyed. What we are doing to ourselves and the planet is absurd.

So, how will we choose to be? What will we choose to do?

I think about Aziraphale’s appeal to his bosses in Heaven, trying to convince them to stop the angelic-demonic war machine that will be the end of everything. The Archangels tell him it’s time to choose sides. To which he responds:

I’ve actually been giving that a lot of thought. The whole choosing sides thing. What I think is that there obviously has to be two sides. That’s the whole point. So people can make choices. That’s what being human means. Choices. But that’s for them. Our job as angels should be to keep all this working so they can make choices.

How I wish there was an Aziraphale-and-Crowley team scheming, plotting, fighting for us, and succeeding in this world. If there is, they have a lot of work to do.

In any case, the saga of Good Omens goes a long way toward undoing the suffocating, insufferable toxicity of Christian apocalypticism. And it has given us “the new love story for the 21st Century,” as Michael Sheen said in his interview on Tennant’s podcast (minute mark 15:11).

I’ll explore that love story next!

Read Parts Two and Three of my Good Omens journey:

Falling In Love with Aziraphale and Crowley: Love Leaves Its Clues

Aziraphale’s Choice: The Tragic Theology & Ecclesiology of Good Omens

And here is a podcast conversation I did about Good Omens on Positively Joy: https://open.spotify.com/episode/4y0gv6KEaBchQUBII2wcZY

Also, check out this excellent article by Maya Gittelman: “Smited, Smote, Smitten: A Reading on Queer Longing in Good Omens.”

And this one by swirlywords: “Good Omens is Heaven for Autistic People – An In-Depth Look.”

Read also:

The Healing Power of “Moonlight”: Race, Erotic Love, and Baptism

Will God Forgive Us? “First Reformed” Film Review

Blade Runner 2049: 5 Star Review

The Rev. Dr. Leah D. Schade is the Associate Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is the co-editor of Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019). Her newest book is Introduction to Preaching: Scripture, Theology, and Sermon Preparation, co-authored with Jerry L. Sumney and Emily Askew (Rowman & Littlefield, 2023).