This sermon, “The Heart of the Earth: Jesus, Land, and Hope,” is part of a four-part series in the Season of Creation. This sermon is for Land and Prairie Sunday.

Texts: Genesis Chapters 3 and 4; Matthew 12:38-40

In January of this year, I visited the Northern Illinois Synod of the ELCA to preach, lead a workshop, and participate in a working group that created the Season of Creation liturgy we are using during these four weeks. I was hosted by Rev. Jeff Schlesinger, pastor of Heart of Illinois Lutheran Parish who took me to see the 4,000-acres Nachusa Grasslands preserve during my visit.

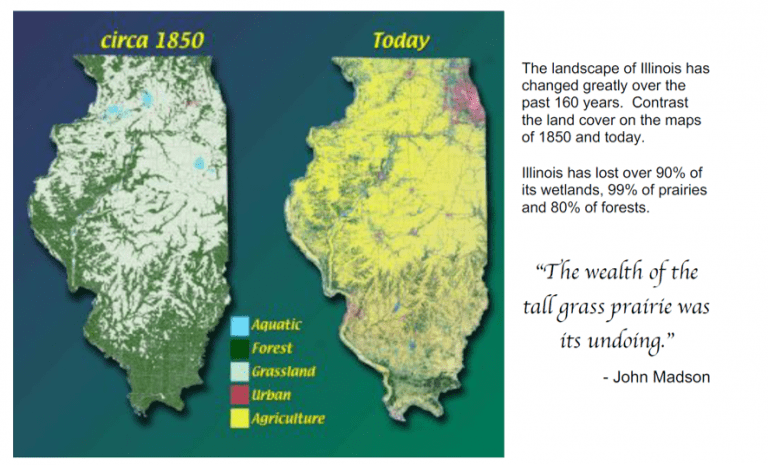

Jeff explained to me that Illinois used to be prairie, woodlands, and wetlands up until the mid-1800’s. But because of its rich soils, the state was gradually converted to agriculture to support the growing and hungry population of the United States.

Much of the forests and prairie are gone. They’ve been replaced with acres upon acres of crops in an industrialized economy of Big Agriculture.

But a handful of people began to advocate for returning some of the land to its natural prairie state. The result is the Nachusa Grasslands that protects and preserves this remnant of land to help restore habitat for one of the largest and most biologically diverse ecosystems in the state. Working hand–in–hand with the Nature Conservancy staff, the volunteers collect and plant seeds, manage invasive species, repair wetlands, and conduct controlled burns. All this and more is done to preserve, protect, and share this precious endangered ecosystem.

But here’s the really exciting part. In 2014, the Nachusa Grasslands reintroduced an endangered species back to its natural habitat – the American bison.

The Nature Conservancy, which operates the Grasslands, brought 30 bison to the preserve and the herd is now over 90 with more calves expected each spring.

For Jeff, his work with Nachusa Grasslands is part of how he lives out his faith.

Caring for the land that God fashioned over millions of years is a sacred trust. Helping to restore the creeks and streams while educating his parishioners and other church folk throughout the synod about this precious and fragile ecosystem is part of his vocation as a pastor and as a Christian.

I think about Nachusa when I read Genesis Chapters 3 and 4. In Genesis, there is a rupture in the relationships between man and woman, humans and animals, humans and Earth, humans and God. Adam and Eve choose to know the difference between good and evil. Cain chooses to act on the difference between good and evil.

The conflict between Cain and Abel echoes in the tension and bloodshed over the use of land that still exists today. Cain was so angry that his brother’s sacrifice found favor with God that he murdered his own flesh and blood.

The blood cries out from the soil.

And that blood cried out from the very soil itself, just as the land always cries out when humans kill each other. Later, when Cain founded a city, he set up a tension between those who live in cities and those who live in rural areas. That tension, too, continues to this day.

We often think of land as real estate, as property to be used however we desire, often without considering our neighbors or the land itself. But here’s the question: is the land ours or does it continue to belong to God? Creation suffers because of human choices throughout history. So can we make different choices that allow for healing and restoration between humans, the land, and God?

In what ways can the land be our teacher?

As we observe the balance within ecosystems – the cycles of production and sabbath, regeneration and renewal – what we can we learn from the land about how to live in community?

Here in Kentucky, we also have a groups of dedicated volunteers who work to protect and restore the land as God had intended it. One that I have come to appreciate is Kentucky Natural Land Trust (KNLT). Established in 1995, KNLT is a state-wide land trust committed to preserving the commonwealth’s diminishing natural places, protecting our rich biodiversity, and ensuring a future that will continue to inspire new generations of environmental stewards.

KNLT works to protect the Pine Mountain Wildlands Corridor that stretches across three states, running right through the southwestern border of Kentucky. Over the past two decades, they have protected more than 3,000 acres of old-growth forests. Pine Mountain is home to a mixed mesophytic forest, which means that it is one of the most diverse temperate forests in the world. It’s the largest conservation effort in Kentucky’s history.

Hiking on holy ground

Three years ago, my son and I were invited to hike Blanton Forest Preserve near Harlan, Ky., on Pine Mountain to see for ourselves just how awe-inspiring this natural lands trust is. It’s the largest tract of old-growth forest remaining in the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

It was as if we were making a pilgrimage into a place of holiness. I breathed in the oxygen-rich air and marveled at the array of life before us. 350-year-old trees arched over us like the vaulted ceiling of a sanctuary. A stream with darting minnows (including some endangered species) flowed down the mountain as we hiked up, its fresh waters reminding me of the source of my own baptism. The congregants were rocks and boulders robed in lichen. Spiders weaving their altar linens. And rhododendrons kneeling in prayer. All of them hushed and reverent. We were standing on holy ground.

Since then, I’ve taken a group of students from Lexington Theological Seminary to Blanton Forest on an immersion trip in Appalachia.

Baptized in the forest cathedral

As we walked, the thunderclouds rolled over the shoulders of the mountains and baptized us right there in the forest cathedral. For some of the students, it was the first time they had ever been in an old-growth forest. The reverence they felt that day has helped many of them to understand their Christian calling as including advocacy for God’s Creation.

This is why I find these words of Jesus in Matthew 12:40 so profound. “[F]or three days and three nights the Son of Man will be in the heart of the earth.” The Greek phrase is en kardia ge, literally “in the heart of the earth.” And “heart” here does not just mean in the center of the earth. Jesus is saying that he is going to that place within the Earth that is the seat of physical life, just like a human heart. This is extremely important for our concept of the created world. These words evoke the notion that Earth is a living entity, for one thing. And that Earth has a center of spiritual, intellectual, and physical life.

This is a revolutionary change in attitude toward Earth from what we see in Genesis. After Eve and Adam violated the Tree of Knowledge, they were forced into an adversarial relationship with the land. Yet in this passage of Matthew, Jesus is saying that he will not rule over Earth, but allow himself to be taken in by it. His crucifixion and resurrection, therefore, is not just for the salvation of human beings, but for the very Earth itself.

This prompts us to ask: what is our individual vocation to reconcile with Creation? What is the church’s vocation to care for and steward the land entrusted to us?

Many churches have large grass plots that are ecological dead zones. They are mowed so there is no animal habitat, no nectar for bees and butterflies. Plus the gas of the lawn mower is destructive to the air and unnecessary use of fossil fuels. What if this land was allowed to return to its natural state? What if butterfly gardens were planted? How might we reconsider our relationship with the very land the supports the church building?

Especially as the climate crisis worsens, we need ecosystems like tall grass prairies and old growth forests to draw down the carbon dioxide that is causing global warming. Trees absorb carbon dioxide and produce the oxygen we need to live. And the deep root systems of prairies allow them to develop resilience to droughts, floods, and wildfires. Reestablishing prairies and protecting forests is one of the best ways to mitigate climate change.

Good for the climate. Good for our Earth-kin.

Plus, the habitats for insects, amphibians, birds, and mammals are vital in these ecosystems. Since the restoration of the Nachusa Grasslands, the ponds have become a natural area that attracts an abundance of diverse species. Even endangered whooping cranes and Sandhill cranes are finding a home for feeding and nesting.

In Blanton Forest, Pine Mountain has become a critical refuge and migratory route that runs through a region. The ridge is a 125-mile intact natural lands corridor where nearly 100 species of rare plants and animals live, some found nowhere else on the planet.

What do you think might happen if the land around the church were able to host threatened species of butterflies, bird, and bees? Could we think expansively about what it means to be a congregation and include God’s Creation as part of that? Imagine our young people and future generations connecting with the beauty of nature right in our own backyard. Imagine church services held amidst the buzzing, chirping, and singing of our fellow worshipers in God’s Creation.

Jesus was taken in by Earth and was resurrected from deep within the tomb. Jesus’ resurrection was for all the cosmos.

Earth, too, experiences a kind of resurrection when we attend to these wild places. We must protect and restore God’s good Creation, and teach our children to love and care for the land.

As it is written, “for three days and three nights the Son of Man was in the heart of the earth.” But the Son of Man holds the heart of the earth for eternity. Amen.

Read also:

Preserving the Holy Remnant: Kentucky Natural Lands Trust

Appalachia doesn’t need saving. It needs solidarity.

Finding Eden’s Forests in the Midst of COVID19

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is also the co-editor of Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/