On Transfiguration Sunday, divinity touches humanity. Transcendence touches immanence. Love touches fear.

During the Sundays of Lent, I’ve been invited to First Presbyterian Church in Lexington, Kentucky, to lead a deliberative dialogue series on “The Role of the Church in a Divided Society.” In preparation for this series, I preached this sermon on Transfiguration Sunday to frame the dialogue from a biblical and theological perspective.

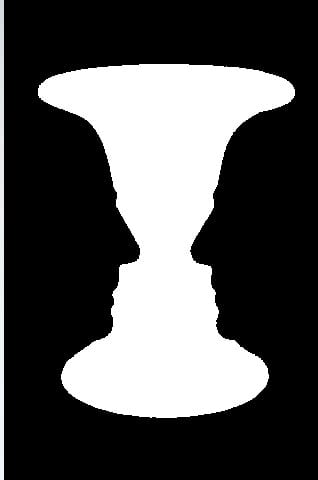

When you look at this image, what do you see?

I remember the first time I saw this picture and the person told me that it wasn’t just a vase in the picture. There are two faces as well. I just didn’t see it at first. Then they showed me – here is the nose, the chin, the eyes, the forehead. And the light went on in my mind. I could actually feel something click in my brain. An a-ha moment. I could see the faces.

Have you ever had one of those moments? Something happens when, all of a sudden, you see. You get it. You understand.

The disciples had one of those moments on the mountain of Transfiguration. Up until this point, they had only seen Jesus in one way—as a human being. Certainly he is a miraculous human being—an amazing man who casts out demons, heals the sick, and preaches captivating sermons. But still, just a human being.

However, Peter was starting to understand that there was something more to Jesus than meets the eye. In the previous chapter, Jesus had asked the disciples, “Who do you say that I am?” Peter correctly answered, “You are the Christ, the son of God.” But when Jesus explained that this meant he must suffer death on the cross and be resurrected, Peter chastised Jesus for saying this. So Jesus tells him that he has his mind only on human things rather than the realm of the divine. He’s seeing only the vase instead of the faces, so to speak.

But here on the mountain, Peter’s mind is forced to reckon with divine things.

These three disciples have ascended the mountain with their teacher and found themselves in the very presence of God. Eyes wide, mouths agape, they see Jesus standing beside the two pillars of the Jewish faith. Moses, the great leader and warrior, the one who led the people out of Egypt and slavery. The one who presented the Torah, God’s holy law, to the people. And Elijah, Israel’s greatest prophet. The one who called the people back to the Torah and into a right relationship with God and neighbor.

Certainly as they gazed on these two figures, the disciples would have remembered the story we heard in the first reading. Moses ascends to Mt. Sinai to receive the commandments of God. He leaves the people at the foot of the mountain while he climbs higher and higher until they can no longer see him. Notice that they each see different things. Moses enters a billowing, all-engulfing cloud of the divine presence that shrouds him from his people. But from the bottom of the mountain, the people see a devouring fire—a fierce, all-engulfing light that seems to consume the whole mountain. So what it is – cloud or fire? Vase or face?

Of course, it is both.

This is what’s known as a theophany—God revealing Godself in an indescribable event of transcendence and immanence all at once.

God is both the pillar of cloud by day and the pillar of fire by night. God is the blazing fire of the burning bush that does not consume. And God is mysterious fog that surrounds Moses in divine secrecy and revelation. This means that Moses is in a liminal space, an in-between place. His feet are touching the earth, but his face is looking to God.

The Celtic people had a name for such a place where heaven and earth come so close to each other that you can catch a glimpse of God’s holiness. They call it “a thin place.” It’s a place where the distance between the sacred and the profane becomes a thin membrane through which the spiritual realm enters into the earthly realm. It’s also a place of disorientation and confusion. We lose our bearings because we are being reoriented. We are seeing the world in a new way. We are seeing God in a new way.

On the Mount of Transfiguration, the disciples are seeing Christ in a new way.

C.S. Lewis once said, “What you see . . . depends a good deal on where you are standing: It also depends on what sort of person you are.” (C. S. Lewis, The Magicians Nephew, in The Chronicles of Narnia [New York: HarperCollins, 2001], 75). This is certainly true for the disciples. After seeing Jesus shining with a brightness that surpassed anything they had ever seen, and seeing Moses and Elijah standing their with teacher, their response is, well, anticlimactic at best. At worst, it’s inappropriate, silly, even sacrilegious.

They want to build three little tabernacles for the holy figures. As if their shelters of branches could house the divine eminence before them. Do they really think they can pin down the sacred and build a tent around it? Hold onto the divine moment for all time in this one place? Are they that audacious to think they can contain the divinity before them? Or are they just that clueless?

Maybe we shouldn’t be too hard on Peter, James and John.

After all, they are encountering something that no other human being has ever seen. Sometimes when you see something for the first time that is completely outside your frame of reference, you just don’t have the mental, emotional and experiential template to make sense out of what you’re seeing.

The disciples were so astounded, so caught off guard, so frightened by the vision in front of them that they just started blubbering whatever came to their minds. They failed to grasp the full importance of what they were seeing.

So the voice of God has to speak to them, spell out for them exactly what they are missing, show them what it is they are supposed to see. A great cloud envelops them. It is similar to the divine cloud that enshrouded Moses on Mt. Sinai. It’s the same kind of thunderous cloud that pulled Elijah up in a whirlwind of glory.

The voice speaks. “This is my Son, the Beloved. Listen to him.”

Here is what you have been missing, says God. This is what you need to see. Now open your ears as well. Follow his teachings.

Peter, James and John are given a vision and their eyes are opened. They see the divinity of Jesus. They see Jesus as the unique Son of God.

The transfiguration is the lens through which they will observe and participate in the rest of Jesus’s ministry and teaching. His arrest, trial, crucifixion and resurrection will all be seen with the light of the Transfiguration behind them. This is a moment of clarity as they prepare for a tumultuous time ahead. The Transfiguration is about the identity of Jesus, his relationship with his disciples, and what they will face when they come down off the mountain.

Transfiguration Sunday is also a moment of clarity for us as we prepare for a tumultuous time ahead.

We live in a time of divisiveness in a country that is in the midst of a crucial reckoning about who we are as a nation and who we want to lead us. All of this has important ramifications for us at the church today.

What is the church’s role in the public square when we are grappling with all this? What is our role as Christians when we’re trying to decide how we live community together? How will we be the church in the midst of this divisive and fractious time? How will we be in ministry together when some of us see vases and others see faces?

Over the next five weeks of Lent, we will have an opportunity to explore these questions. We’ll be undertaking a process called deliberative dialogue in which we will gather for Adult Sunday School using an issue guide called “The Church’s Role in a Divided Society.”

Deliberative dialogue is a form of civil discourse that brings people together to discuss an issue of public concern.

It was developed by a group of research associates at the Kettering Foundation and National Issues Forum Institute, organizations that helps ordinary citizens learn how to do democracy better. The purpose is to listen deeply to each other’s experiences, weigh the benefits and drawbacks to different approaches to the issue, and discern common values we share. The hope is that we might determine different actions for the future that are in alignment with who we are and what God has called us to be.

You see, being the church means being with people who have different values, different perspectives, even misdirected commitments (like the disciples wanting to build tabernacles).

But notice – Jesus does not kick them off the mountain when they get it wrong.

In fact, you can see how much Jesus cares for the disciples by looking at the verbs used. He “takes” and “leads” them up to the mountain. And after they hear the voice of God and are cowering in fear, what does he do? He “touches” them. He says, “Arise. Do not be afraid.”

There in that thin place, divinity touches humanity. Transcendence touches immanence. Love touches fear.

I don’t know if our deliberative dialogue over the next five weeks will take us to a “thin place.” But it might. Encounters with the holy don’t just happen on mountaintops amidst billowing clouds or consuming brightness.

Sometimes we encounter the sacred in the taking and leading, in the touching with tenderness. And in the listening.

God speaks to all of them about who Jesus is (my Son, the Beloved) and what they are to do in response (listen to him). So The primary question I will want us to ponder over the next five weeks is this. How do we listen to the voice of Jesus in the midst of our dialogues, our sacred exchanges, our holy discussions?

It’s not easy to do. Our limited human minds have difficulty overlaying two seemingly opposing visions. Face or vase? It’s a paradox, a mystery.

But even when we are afraid as we enter into highly-charged holy moments (as many dialogues can be), we can trust Jesus’s presence among us, assuring us not to fear. The disciples saw the light radiating from their teacher and they heard the voice of God saying that this was indeed God’s Son. It was a moment of wonder and awe.

What it takes in order to see these two opposing visions is . . . holy imagination.

Because we don’t just see with our physical eyes. We see with our minds, with our hearts. What Jesus is trying to do with the disciples, he’s also trying to do with us. He’s trying to help us see. He’s trying to open our eyes, open our ears, open our hearts to perceive the possibilities that God is showing us for healing this world, for transfiguring this world.

So I invite you to enter this “thin place,” this holy conversation with each other, being guided by Jesus, being touched by his hand and listening to his voice: Arise. Fear not. The presence of God is here.

Read also:

Reading Matthew 17:1-9, Transfiguration of Jesus, Through a Dialogical Lens

Choose Life, Hope at the River’s Edge: Moses’s Final Sermon

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and ordained in the ELCA. Dr. Schade does not speak for LTS or the ELCA; her opinions are her own. She is the author of Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), Rooted and Rising: Voices of Courage in a Time of Climate Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015).

Leah’s latest book is a Lenten devotional centered on Creation: For the Beauty of the Earth (Chalice Press, 2020).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/