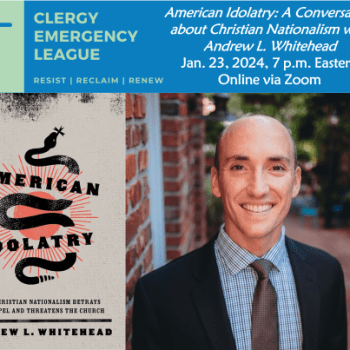

Toni Morrison has just died at the age of 88. Here’s why her book Beloved helped form me as a Christian confronting my own racism and constructing my understanding of public theology.

When I was a PhD student at the Lutheran Theological Seminary in Philadelphia, Toni Morrison’s book Beloved was on the reading list for the Public Theology portion of my program. Initially I wondered why, since it’s a work of fiction. It’s not a theological treatise, but rather a novel about a group of former slaves and their children surviving antebellum America. In the midst of dehumanizing white supremacy, with its horrific crimes against black men, women and children, the story focuses on Sethe. She is a woman with a secret anguish that haunts her family and surrounding community.

The story begins with the sudden convergence of people from Sethe’s past arriving at her home. Paul D is a friend from her former enslavement at Sweet Home. Then the mysterious Beloved arrives just after Paul D banishes a destructive, haunting spirit from Sethe’s house. What follows is an evocative, troubling saga. In Beloved, Toni Morrison poetically and poignantly portrays the power of incarnate love to enter into the most broken and scarred places of our lives to nurture tentative tendrils of hope and redemption.

Beloved had a profound effect on me, a white, female Christian and preacher preparing for a vocation of public theology and teaching.

I happened to be reading Beloved as I was ministering to an African-American congregation, Spirit and Truth, in Yeadon, Pa., while working on my PhD program. Morrison’s book helped me recognize my own complicity with the racist system that still exists in this country. She was able to articulate for me the source of fear that whites have of blacks.

In the book, Sethe is accused of being an animal, not just by her white owners, but also by the man she loves. Whites see within blacks a primal, chaotic, jungle-like nature that threatens to overcome “civilized “white society with its untamed power. What whites do not recognize – Morrison’s book makes clear – is that the jungle they fear within blacks is the one they planted there by their enslavement of the people of Africa.

Here is a quote from Chapter 19 of Beloved:

Whitepeople believed that whatever the manners, under every dark skin was a jungle. Swift unnavigable waters, swinging screaming baboons, sleeping snakes, red gums ready for their sweet white blood. In a way, he thought, they were right. The more colored people spent their strength trying to convince them how gentle they were, how clever and loving, how human, the more they used themselves up to persuade whites of something Negroes believed could not be questioned, the deeper and more tangled the jungle grew inside.

But it wasn’t the jungle blacks brought with them to this place from the other (livable) place. It was the jungle whitefolks planted in them. And it grew. It spread. In, through and after life, it spread, until it invaded the whites who had made it. Touched them every one. Changed and altered them. Made them bloody, silly, worse than even they wanted to be, so scared were they of the jungle they had made. The screaming baboon lived under their own white skin; the red gums were their own.

This is the “heart of darkness” jungle (to borrow Joseph Conrad’s term) that imposes ruthless domination on a people.

This domination results not just in their enslavement, but in the ongoing institutional racism and internalized oppression blacks experience today. In this way, the jungle whites fear is the jungle we put there ourselves. This means that the jungle is actually within us. We have projected onto dark-skinned people the “shadow self” of our own evil proclivities.

So what does Morrison’s novel have to do with public theology?

An important term I learned in grad school was epistemology – the study of how we know what we think we know. I learned that experience is a powerful form of knowledge. Beloved demonstrated that knowledge of the experience of the most violating kind of evil is necessary to create a public theology. Such a theology can listen to the victims of evil and stand in solidarity with them as they struggle to regain their identity, define their personhood, and defend their right of existence and speech.

Reading Beloved helped to put a human face on why Christians must do the work of public theology. We need to try to deeply understand those who have been “othered” by white supremacy in order to experience a conviction of our souls. In this way, we can begin to repent of our arrogance and the way we create hierarchies based on perceived difference. Only in this way can we begin to work on our recovery from our addiction to privilege, humble ourselves, and undertake the work of a theology in the public square.

But Beloved also shows us another kind of epistemology.

It’s a way knowing that enables us to understand deep, embodied, and sensuous grace. Mark Wallace, in his book, Green Christianity, uses the love story of Sethe and Paul D to illustrate what he sees as a necessary corrective of a hardened intellectual epistemology. In Beloved, we experience the embrace of a radical, flesh-loving, Creation-loving theology that honors bodies – human bodies, plant and animal bodies, and the body of Earth herself.

Tragically, it is Sethe’s desperation to protect the precious body of her daughter that leads her to commit murder. Because of what she suffered as a slave, she sees no other option for her daughter than to have her in heaven rather than in hell on this earth. Thus the violence of white supremacy is turned on Sethe’s own child.

Yet Sethe is not beyond redemption.

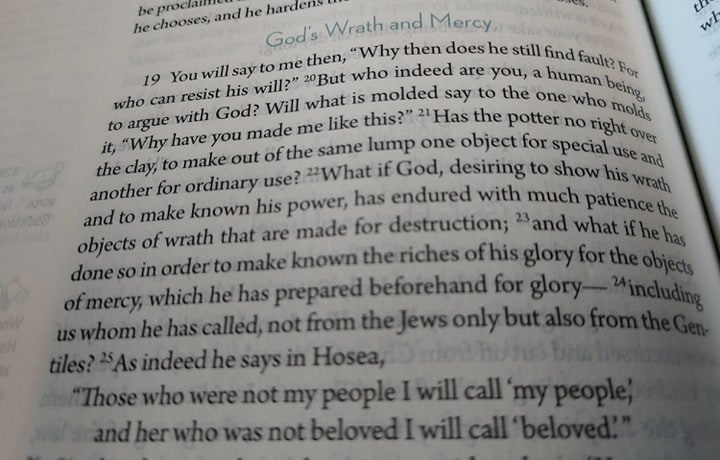

“I will call them my people, which were not my people; and her beloved, which was not beloved” (Romans 9:25).

We have to understand Sethe’s story in light of this verse from Romans. This belovedness is the quiet hand of God running through the story. It’s the tender hands rubbing the swollen feet of pregnant Sethe and binding the festering whip-wounds on her back. It’s the female preacher Baby Suggs raising holy hands above the gathering of children, men, and women in the clearing, blessing them holy words that urge them to love the very bodies that whites have colonized and terrorized.

“You got to love your hands. You got to love your heart,” she declares to them in an outdoor sermon amidst a sacred grove of trees. As a preacher and a teacher of preachers at a seminary, the character of Baby Suggs showed me the power of connecting a broken people with the healing power of God.

So, yes, Beloved should be required reading for Christians.

This is a book for any Christian intent on asking public theology’s hard questions about how power is wielded by the privileged as well as the oppressed. Sethe had power to kill her own child, despite her love for her daughter. When Paul D asserted that there must have been another way, Sethe insisted that the only way to save her baby was to kill her.

Only with Beloved’s return for a reckoning with Sethe, does she begin to learn that there is another way through the evil.

It comes by way of the community of women gathered to exorcise the demon-spirit-child and free Sethe and her other daughter, Denver, from its unrelenting rage. It also comes when Sethe turns her rage on Mr. Bodwin (whom she mistakes for her former slave-owner, Schoolteacher). She redirects her protective violence where it should have been in the first place – against the source of her oppression, instead of against the innocent child who might be the oppressor’s next victim. This redirection aids the exorcism as well.

Being a Christian means we have to listen to these stories, attend to the pain, confront the evil, and – with humility in the public square – invite our communities into the working of the Spirit.

Beloved brought this to light and life for me. Toni Morrison’s exquisite writing has the power to open minds, change hearts, and transform lives. I am grateful to be one of them.

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky. She is the author of Preaching in the Purple Zone: Ministry in the Red-Blue Divide (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019) and Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/

Read more:

Hi, I’m Leah. I’m a Recovering Racist.

The Healing Power of ‘Moonlight’: Race, Erotic Love, and Baptism