We don’t know how the story of the Prodigal Son ends. That’s where grace begins for my sister and me.

Who do you relate to the most in the story of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15: 1-3; 11b-32)? The parent dealing with two feuding siblings? The younger child who has made mistakes and is in desperate need of forgiveness? The older child who feels he’s done everything right, and now watches this undeserving brother get the party that should have been for him?

We think of the younger son as the one who has “wandered and squandered,” separating himself from the love of his father and family. But, in fact, the older son is just as starved and homeless as the younger son. It is his pride and self-righteousness that separates him from the love of his father and family.

Ironically, both sons are yearning for the same thing – the love of their father.

This feast that the father calls for is his way of demonstrating and celebrating that love. This extravagant meal, this surprise party, is the father’s way of saying, “Come to the table. Your sins are forgiven. Eat, drink, celebrate your fellowship with each other and with me.” Because God loves us, we are invited to the table, despite our sins. We’re given a surprise party! It’s a party we don’t deserve, but it sweeps us up into the grace of God.

Can you remember a time when you were surprised with a gift or a party that you didn’t deserve?

When I think of that question, a story from my own life comes to mind. It’s about a surprise party that my family planned for me for my 16th birthday.

I’m the oldest of four, and so I can really relate to the eldest brother in this story. I always played it straight, walked the line, was the good child in my family. And it always angered me how much my younger siblings got away with. In fact, I would have to say that my siblings and I did not get along well growing up. This was especially true between me and the second oldest child, Ivy Jo.

Ivy Jo was a year younger than me and was born with some physical disabilities. She was confined to a wheelchair most of her life. There was animosity between us probably from the moment my parents brought her home from the hospital. I was jealous of her because of all the attention she got. And she was jealous of me because I could walk and run. I was independent and free – something she would never experience.

The older we got, the more the bitterness grew between us.

We were, frankly, very mean to each other — always looking for ways to insult the other, bring the other down. We brought out the worst in each other’s personalities.

Because we were so close in age, we were only a grade apart in school. While she had her set of friends and I had mine, our lines of friendship often overlapped at school and at church. And we brought our animosity towards each other into our friendships.

So when I noticed Ivy whispering behind my back to my friends over a series of weeks, I was furious. I’d catch her talking to them, they would laugh, and then she’d scoot away in her wheelchair as I came over. She was trying to turn my friends against me!

I’d ask them, “What did she say about me?” And my friends would just shrug and say nothing. I was so angry at them, and furious with her. Over and over I would come upon her talking to my friends and then buzzing off in her wheelchair, obviously trying to aggravate me. I confronted her several times. “Why do you keep talking to my friends? Stay away from them!”

“I can talk to whoever I want,” she say. “It’s a free country.” And she’d have this smirk on her face that just drove me crazy.

This went on for a couple weeks. Then one evening, my dad picked me up from a play rehearsal to take me to meet my aunt to celebrate my birthday with a nice quiet dinner. He made an excuse to stop at a dance club called Zakies, claiming he had to pick up some papers for a client. We went into the club, up to the second floor.

I walked through the door and heard, “SURPRISE!”

There was my family and all my friends from school and church all gathered together in that room! I was shocked to tears. I couldn’t believe it! How had they managed to pull this off without my finding out?

My mom told me that, of course, they couldn’t send out any written invitations because I might find one by mistake. So Ivy Jo volunteered to talk to each one of my friends and invite them to my party.

In a rush of emotion, it all became clear to me. All this time I thought she had been sowing more seeds of hatred, when, in fact, she was giving me the gift of this party that I didn’t even deserve. I went over to her and gave her a big hug and thanked her for what she had done. I have a photograph of the two of us embracing, a look of tearful joy and excitement on my sister’s face.

I cherish that photograph.

Because nearly twenty years ago, Ivy Jo took her own life.

I’d like to say that things changed between us after that moment at the party. I’d like to say that our relationship was positive from then on. Unfortunately, our relationship continued on a roller coaster of a few ups, but mostly downs. At the end, we were not speaking to each other. Ivy Jo suffered not only from her physical disabilities, but from many emotional ones as well. This led to addiction and isolating herself from our family. Many of us, myself included, pulled away because the relationship was so hostile and painful. Today I still live with regret and unresolved guilt and pain.

One of the reasons I find the story of the Prodigal Son to be so poignant is that we do not know how it ends.

The elder son is faced with a decision that, in any case, is going to cost him something. If he stays outside, he’ll retain his sense of righteousness and pride, the knowledge that he is right. But that will cost him his relationship with his father and brother. If he relents and goes into the party with his father, he will hopefully enjoy a reunion with his brother. But it will cost him his pride and self-righteousness.

Even if he goes to the party, there’s no guarantee that that moment of embrace between the two siblings will be the happy ending everyone is looking for.

We don’t know whether the younger son will learn from the error of his ways and be a good, obedient son from now on. Or if he will continue to take advantage of his father’s goodwill and goad his brother. We don’t know if the older brother will forgive his sibling for squandering the family inheritance, or will quietly resent him and act out his bitterness in small ways for the rest of their lives.

The only person we’re sure of in this family is the father. The only person who has proved himself as consistently loving to both siblings is the father. Some scholars have suggested that this story not be called the Prodigal Son, but the Prodigal Father. Prodigal means “recklessly extravagant,” “wasteful,” “lavish.” We call the younger son prodigal because he is recklessly extravagant and wasteful with the inheritance from his father. But the father is prodigal, too — recklessly extravagant with his love for both sons.

This is a father unlike any that Jesus’ hearers would have encountered during their time.

A wealthy man in the time of Jesus would never have acted the way this father did towards his children. First of all, he would not so easily have given up the portion of his estate to his younger son without question. It was an insult for the son to ask for it in the first place, because it implied that he regarded his father as dead to him already. But without a word, he hands it over to the boy.

When the son finally does come back, the father is again scandalous in his expression of love.

A rich man would never run out into the street to embrace his pig-smelling, wayward son. At most he would have whistled for his servant to escort the son home while he waited imperiously on the porch, ready to dole out the proper punishment for the boy’s misdeeds. But this father makes an utter fool of himself for this child. He runs with abandon to take the child in his arms, shower his dirty, smelly face with kisses, and dress him with fine clothes and jewels. He lavishes a feast upon the boy, killing the fatted calf that should have been saved for a religious ceremony.

And that’s not all! When his older child refuses to come into the party, the father, again, makes a fool out of himself. He should have sent a servant out to order him into the party, “Your father says, ‘You will go to the party, and you will welcome your brother, and you will smile and enjoy yourself.’”

But no, the father goes out himself, pleading with his son. No self-respecting rich man in Jesus’ time would beg his child like this. And when this hot head sasses his father with such venom, he could have responded, “How dare you talk like that to me, you ungrateful boy. Now get in there right this instant!” But, no, he talks with him compassionately. “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours. But we had to celebrate and rejoice, because this brother of yours was dead and has come to life; he was lost and has been found.”

And that’s it. We don’t know how the son responds. We do not know the end of the story.

But we know the father has the last word.

This is what gives me some measure of hope when I think of my sister. We do not know the end of that story yet, either. Right now, I am standing in a place where there seems to be no hope. She is gone. There’s no chance in this lifetime for me to reconcile with her, or her with me. There is an awful feeling of regret and loss in this place.

Perhaps, you, too, have known that feeling.

Maybe you have experienced conflict with a sibling or a family member that has plagued your household for decades. And no matter how you try, you keep coming up against dead-ends, painfully running into the same brick walls.

I think, too, about the painful conflicts in the larger human family. Every time I hear about civil war in some nation, where countrymen and brothers hate each other to the point of murderous rage. As I watch the deteriorating situation in the Middle East, where Jewish, Christian and Muslim children of Abraham continue to slaughter one another. Every time I hear about another terrorist attack, or a murder — I know that they are not so far removed from me, a pastor, who could not even reconcile with her own sister.

So where is our hope?

Where is the good news for us who, for whatever reason, find ourselves outside the party?

Our only hope is in that father. Our only hope is in God –

this God who lavishes undeserved love on both children,

on Ivy Jo and me.

This God who makes a fool out of himself by coming to each of us where we are and inviting us back home, surprising us with this undeserved party, begging us to come to table.

This God who will go to even greater lengths than this,

ultimately sacrificing his own life for us,

to break our hearts,

and open our hardened spirits toward each other,

reconciling these two sisters,

these feuding families, these warring nations.

Indeed, as Paul says, God in Christ is reconciling the whole world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting the message of reconciliation to us . . . (2 Cor. 5:19)

And so I know . . . I trust . . .

I have faith that God will have the last word.

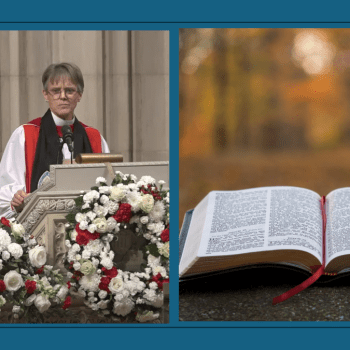

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary (Kentucky) and author of the book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/

Read also:

Receiving the Right Yoke: A Sermon on Burdens and Stress