The election of two female African American bishops in the ELCA may be a turning point for the church. The biblical story of Hagar helps us frame this historic event to see how women of color are stepping out of the wilderness and into positions of leadership within the church.

Did you hear that?

It’s the sound of shards falling from the church’s stained-glass ceiling.

It’s what we heard when two female pastors of African-descent ascended to the position of bishop in their respective synods in the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

The Southeastern Pennsylvania Synod made history Saturday, May 5, 2018, when its assembly elected the denomination’s first female African-American bishop – the Rev. Patricia A. Davenport. One day later, the Rev. Viviane Thomas-Breitfeld, a pastor in Beloit, Wis., was elected in the South-Central Synod of Wisconsin.

This is the sound of Temple curtain tearing, the barriers coming down.

The importance of these votes cannot be overstated in a denomination that, according to the Pew Research group, is racially 96% white – the “whitest” among the denominations. And in a country that cannot bring itself to elect a female president – much less include a female of color on the ballot – the fact that the church has lifted up these women as their leaders is incredibly significant. It disrupts the narrative that the church is behind-the-times, woefully out of touch, and unresponsive to the changing culture. This is one time that the church is actually ahead of the curve, out in front, and leading the way.

This is the sound of Miriam with her tambourine.

Certainly, this is not the first denomination to raise up women of color to its highest positions of leadership. For example, Bishop Leontine T. C. Kelly was the first African American woman elected Bishop in the United Methodist Church in 1984, and the UMC elected four more as recently as 2016. The Rev. Vashti Murphy McKenzie was elected bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 2000. The Rev. Teresa “Terri” Hord Owens was elected as the General Minister and President of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) in 2017.

And at Lexington Theological Seminary where I teach, I am proud to serve under the first female African-American president in the school’s history – the Rev. Dr. Charisse Gillett. And just last year, our seminary called its first female Hispanic Vice President of Academic Affairs and Dean – the Rev. Dr. Loida Martell.

This is the sound of Hagar emerging from the wilderness.

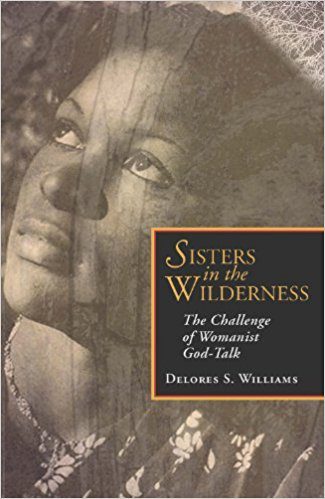

A book by Delores Williams called Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk (Orbis, 1993) gives us a biblical framework for understanding the significance of the rise of women of color to positions of leadership in the church.

Williams is a pioneer of womanist theology who interpreted the story of Hagar through the lens of African American slavery and its fallout of internalized oppression. (Womanism is a social theory that focuses on the experiences of black women.) She explained how black women today are like the Egyptian slave girl in Genesis Chapters 16 and 21, and have been overlooked as having a unique, empowering, contesting knowledge of God through direct encounters in the wilderness.

Hagar – the one who gave God a name

Briefly, Hagar was the slave-girl whom Sarah gave to Abraham as his concubine. Hagar bore Ishmael but ran away to the wilderness to escape Sarah’s jealous fury. God’s angel convinced the pregnant girl to return to her servitude, but when her mistress bore her own son named Isaac, the rivalry between them intensified. Sarah and Abraham expelled Hagar and her son to the wilderness where they faced starvation. Yet God provided water and promised that her son would become a great nation (he is the progenitor of the descendants of Islam).

Williams saw Hagar as epitomizing the experience of slaves and their descendants in the United States. She identified Hagar’s story of slavery, sexual exploitation, surrogacy, and poverty as the nexus in which women of color must construct their theology. Notably, Hagar is the only one in the Bible who gives God a name – “The One Who Sees.”

So she named the Lord who spoke to her, “You are El-roi”; for she said, “Have I really seen God and remained alive after seeing him?” (Genesis 16:13).

Williams urged women of color to reclaim their fore-sister’s singular act of naming God for themselves and moving beyond mere survival into a mode of being where they can begin to flourish.

She further highlighted the significance of bodily knowledge for black women. Suffering and humiliation, as well as visceral joy and celebration, are all part of the incarnation of Christ within black women’s bodies. More generally, women’s experiences of sexuality, childbirth, rape, abuse, and intimate love are all important sources of theological reflection, especially in light of God’s decision to incarnate as the fully fleshed human being of Jesus Christ.

It follows, then, that when the church structure relegates women to subservience and irrelevance, it must be called out and reformed.

For too long, mainline Protestant churches have ignored and dismissed black women’s experience, while simultaneously upholding sexism and the oppression of women of color. Williams noted that because of their experience coming from a history of slavery and servitude (which continues for many to this day), black women have been given a distinctive perspective on survival and the function of their faith in that struggle. These sisters in the wilderness are uniquely equipped to resist oppression and encourage the other marginalized peoples in claiming what they know of God in their bodies, hearts, minds, and relationships with each other.

Hagar was oppressed, yet resourceful. She was rendered powerless, yet found a way to claim her own power in the wilderness. She found herself in desperate circumstances, yet realized she was sustained by God. These new leaders embody the spirit of Hagar as well.

In her book, Williams honestly assessed the way the church has both helped and hindered the development of black women. On the one hand, their faith in God and the church is what enabled them to get through “one more day” and keep hope alive in the midst of slavery and its aftermath. But this same church, Williams argued, has manipulated, exploited and coerced black women in ways that take advantage of their faith.

This makes for an interesting dynamic when black women try to answer the call to preach. The church has traditionally dismissed female preachers and openly defied and undermined their calls and positions of ordained leadership. Black women have to had to struggle mightily just for a hearing in the church.

This is the sound of sisters EMERGING from the wilderness.

In the spirit of black women preachers such as Jarena Lee and Sojourner Truth, today’s rising women of color are now leading the church. They are uniquely equipped with boldness and fearlessness forged out of the need to confront both racism and sexism in pulpits that are often hostile to their presence.

Another key element to their leadership is authenticity. They share a commitment to being who they are and bringing every aspect of their lives, their womanhood, their race, and their cultural background with them. At the same time, women of color have had to become “bilingual” in their speech and rhetoric so that they can appeal to a white audience, while still retaining their self-identity as black women.

This is the sound of the CHURCH emerging from the wilderness.

In an interview with Carol Kruvilla of HuffingtonPost, Davenport said she hopes these elections become a “tipping point” for the ELCA.

“I was the first of two African Descent women who have pushed through the door marked ‘for Whites only’ for 30 years too long,” she wrote. “Change has come because people of color will be at the table, even more so because we are resilient, equipped and willing to live into the Prophet Micah’s call, ‘To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God’ on behalf of those who have elected us to serve.”

Amen, Sister! The wilderness has formed you and your sisters to show us the way into the church’s future.

Lead on!

Read also: An Iconic Moment: ELCA Synod Elects First Female African-American Bishop

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary (Kentucky) and author of the book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015). She is an ordained minister in the Lutheran Church (ELCA).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/.

See also:

#MeToo, #ChurchToo: The Church is Facing the Truth About Its Sexism

Preaching Hagar and Ishmael when Philando is on Screen

James Cone: One White Woman’s Tribute