Preserving the Holy Remnant: Kentucky Natural Lands Trust

The first thing I noticed was the sweet, pungent aroma of sunset-colored leaves in autumn. The trees breathing out their moist, oxygen-rich exhalation. Moss-carpeted rocks and soil draped in emerald beauty, giving off their earthy scent.

Breathe in that air!

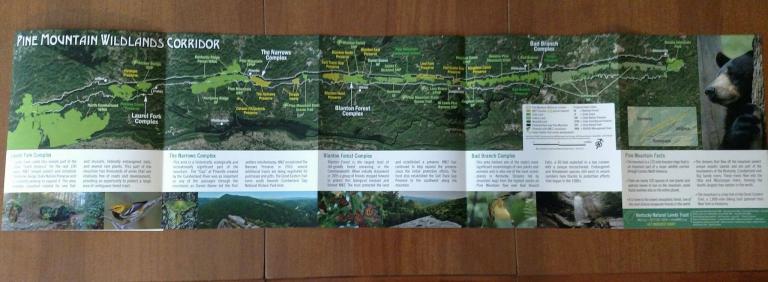

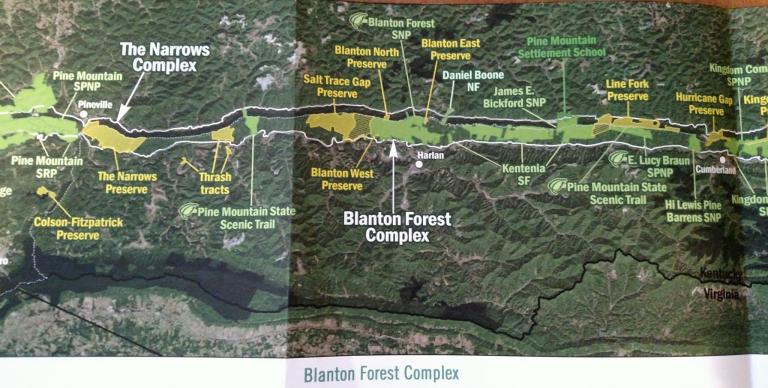

As we walked with our guides into Blanton Forest Preserve on Pine Mountain, Kentucky, my 10-year-old son Benjamin and I breathed in the air and marveled at the array of life before us. Blanton Forest, near Harlan, is the largest tract of old-growth forest remaining in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. In 1995 a group of friends discovered the rich biodiversity of these woods and decided to work to protect the land. This was the start of Kentucky Natural Lands Trust, a state-wide nonprofit committed to preserving the last remaining natural places in the state. Their goal is to protect Kentucky’s rich biodiversity and ensure a future that will continue to inspire new generations of environmental stewards.

Entering the forest cathedral

We hiked into the 3,510-acre preserve with KNLT’s Executive Director, Hugh Archer, Program Director, Donna Alexander, and Board Member, Laurie Keller. It was as if we were making a pilgrimage into a place of holiness. 350-year-old trees arched over us like the vaulted ceiling of a sanctuary. A stream with darting minnows (including some endangered species) flowed down the mountain as we hiked up, its fresh waters reminding me of the source of my own baptism. The congregants were rocks and boulders robed in lichen, spiders weaving their altar linens, and rhododendrons kneeling in prayer – all of them hushed and reverent.

We were walking on holy ground.

Pine Mountain is home to a mixed mesophytic forest, which means that it is one of the most diverse temperate forests in the world. It’s the largest conservation effort in Kentucky’s history, where native plants and wildlife are allowed to live without threat of chainsaws, bulldozers, or drills. No hunting, fishing, or trapping will threaten the animals. The way God’s hand fashioned this land is the way it will remain. Human visitors are permitted, but are to leave no trace of their visit when they’re gone.

An Eden oasis

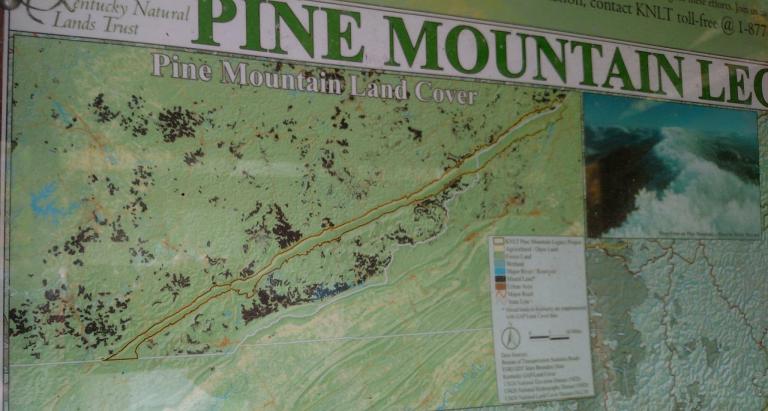

As we walked, I kept thinking of the garden paradise established by God for human beings in the first two chapters of Genesis. For my son and me, it was like discovering an Eden oasis right here in Kentucky. And yet when we looked at the map of coal mining sites lining the ridge on both sides, it was a grim reminder that the sanctity of this place is hemmed in by relentless human pressure all around.

Just a few miles beyond this sacred place is the other side of the Eden story – where the ground is cursed and human beings are engaged in constant battle with the Earth from which they were brought forth.

A “holy remnant”

Pine Mountain is a critical refuge and migratory route that runs through a region with extensive resource extraction. We might say that this land is a “holy remnant” of what God had created. In the Hebrew Bible, the people of Israel were attacked, their land and temple destroyed, and their people taken away as slaves into foreign lands. The ones who survived were called a “holy remnant.” The word remnant means “what is left,” particularly what may remain after a battle or a great calamity. Although remnants are often regarded only as worthless scraps, God assigned high value to those who were left. And that remnant had a holy purpose – to carry the memories of their people, and to rebuild for the next generation.

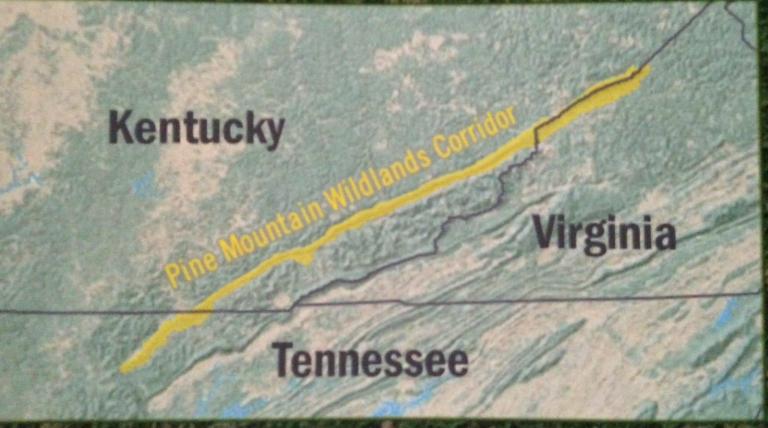

Pine Mountain is part of a “holy remnant” of the untouched forests that remains after humans have ravaged the land since the Industrial Revolution. The ridge is a 125-mile intact natural lands corridor in the midst of coal country stretching from Virginia through Kentucky to Tennessee. There are nearly 100 species of rare plants and animals known to live on the mountain, some found nowhere else on the planet.

Why donate to a natural lands trust?

Sitting at dinner the evening before our hike, Hugh explained that their efforts of preservation are made possible by the thousands of donors who give their money for the purpose of saving these holy remnants. I asked Hugh why people decide to give their money to preserve these places? Is it for name recognition? Ego? Why do they donate to KNLT?

“Most of them don’t want their name listed, so ego is not a big factor,” Hugh clarified. “They want to preserve what’s left of these old-growth forests. Many donors have roots in Kentucky. They want to give something back.”

Donna noted that many of the donors say, “Even if I never get to go there, just knowing that the land exists and that is protected is enough.”

“Many of them are like us,” added Laurie. “They wandered in the woods as kids, turning over logs to see what’s underneath.”

I was one of those kids.

The woods of my childhood were the other “church” I attended in my youth. I spent countless hours in the patch of woods near my house building forts, living a secret life of adventure away from grown-up eyes. Some of my best friends were the trees where I would climb to sit among the branches reading Ray Bradbury and C. S. Lewis books. Yes, I was a “tree-hugger.” And the trees hugged me back, cradled me, even. This was my hide-out from mean kids, my sanctuary from a chaotic home life, and the sacred space where my buddies and I would meet for hours on end of unstructured, imaginative play.

Then one day the bulldozers appeared.

Yellow tape cordoned off the trees silently awaiting their execution. We watched in horror as the wooden sentries of our youth were ripped up from their roots. In less than a day our childhood had been razed to a flat, brown expanse. They would be building houses for humans over the place where we had played.

As a young person, I mourned the losses of these natural places as I had my own grandparents.

Adults’ total disregard for the “feelings” of the trees and animals had caused me much pain and sadness as a child. I instinctively felt an intimate connection between these sacred places in nature and my own small self, a connection that felt deeply violated whenever I helplessly witnessed the destruction of these wild landscapes. I was angered and frustrated to tears that I could do nothing to anticipate or speak out against the planned decimation of my favorite wooded places, much less prevent their deaths.

When I would try to talk to the adults in my life about my concerns, they would gently explain that the rights of those who owned the land superseded the needs of the land itself, not to mention those of a little tomboy. No argument I could make for the “rights” of the land and its other-than-human occupants withstood the argument which ended all discussion: money. End of conversation.

But it’s not the end of the conversation for the One who created the land.

Chapter 3 of Genesis shows us that God set out limits for human beings in how they were to exist in the garden. They were forbidden from eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge. For the good of Adam and Eve, for the good of the tree, for the good of the entire garden, God essentially said: “This far and no farther.” God established a boundary for the mutual protection of the relationship between humankind and the created world.

Did the original humans respect these boundaries? No.

They did not obey the limits God set for them. They ignored the warnings, flouted the rules, and crossed the line. There’s almost a feeling of entitlement you sense from Eve and Adam’s rationalization of their disobedience. It’s as if they’re saying, “This is our garden after all. God gave it to us. We should be allowed to do anything we want with it. Look, the fruit is good to eat. The sale of the wood and the resources in the ground will enrich us. As the Tempter said, God is just afraid that we’ll know what God knows. And why shouldn’t we know?”

Now we know.

We are learning that there are limits as to what Earth can withstand. There are boundaries that need to be established and respected. But we have done more than just cross the line. We have decimated the entire garden. And we are now living with the consequences of a planet whose climate and landscapes are changing too rapidly for the atmosphere and ecosystems to adapt.

That’s one of the reasons the preservation of Pine Mountain is so necessary.

It’s an example of “resilience modeling,” meaning that the various altitudes within the preserve allow flora and fauna to move freely to higher elevations as the temperature warms.

Blanton Forest and other tracts within the corridor will be important places to study as the effects of climate change alter the migratory patterns of animals, birds, and butterflies. Think of it as a sort of “living laboratory” enabling us to observe the changes on this planet to areas that are otherwise protected from human hands.

“But I’m not an environmentalist. Why should I care about the preservation natural lands?”

I get this question from time to time when talking about my passion for protecting the natural world. Others ask, “What good is a forest if we can’t sell what’s in it? Or put up a resort to enjoy the vista? Or clear the land for agriculture?”

What people often do not understand is that wildlands represent a wealth of “natural capital.”

The resiliency of local, regional, and global communities depends on functioning natural systems that can withstand threats through adaption and change. This is of particular importance in the face of a shifting climate. For example, Kentucky growing season is already changing from Zone 6 to Zone 7. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Kentucky is generally one 5-degree Fahrenheit half-zone warmer than the previous map showed from 1990. This warming is being recorded throughout much of the United States.

What difference will it make to protect these forests?

Keeping natural lands “wild” not only stabilizes of the ecosystem for the state, it is also vital to both economic and human health.

Untouched forests are huge “carbon sinks,” meaning that they absorb the carbon dioxide which is playing havoc with the climate. The longer we protect these lands – and the more lands we place under protection – the better it will be for everyone, human and other-than-human alike.

This far and no farther

Pine Mountain is a beautiful example of human beings finally obeying the command of God in the Garden of Eden – this far and no farther. And every time another tract of land is saved through Kentucky Natural Lands Trust, it means that the wildlife, plants, water, and soil of that place can never be destroyed.

No bulldozer will rip an ancient oak tree up from its roots. No luxury home will displace a den of foxes. No mown soccer grass will supplant the carpet of moss and cedum. No parking lot will ever be paved over a wetland that absorbs and filters the rainwater from the surrounding hillsides.

Sometimes there is great blessing in establishing boundaries and protecting them.

Sometimes foregoing short-term profit in order to preserve a natural legacy reaps rewards far beyond monetary wealth. And sometimes the best way to know who we are as human beings is by walking through these primeval forest cathedrals.

The poet David Whyte writes in his book, Midlife and the Great Unknown, about his growing realization that if he did not pay attention to the wild places, not only would they disappear, but so would he. “If I wasn’t paying attention, it seemed there was nothing coming towards me to find me.” He would lose his sense of belonging, his sense of self. “Without any faculties of attention, there was actually no person to be found. My identity actually depended on how fierce of attention I was paying to the world. If I wasn’t looking, listening, feeling, then there was no one to have the conversation with.”

Protecting natural lands is integral to my faith

As a Christian, as a clergyperson, and as a seminary professor, I am committed to helping people learn how to do their part to care for God’s Creation and support eco-justice issues. We need to put in place the strongest protections possible to defend public health, the fragile atmosphere of our planet, and the communities – both human and other-than-human – that will bear the costs and suffering from climate change, pollution, and loss of wild places.

Proud to be a “tree hugger”

As my son and our guides continued on the trail, I kept lagging behind, beckoned by lacy leaves and sea-shell-shaped fungus to look, look, look.

And, yes, I did hug several trees. To steady myself on slippery rocks and steep inclines, I placed my hand upon sturdy trunks. And sometimes I would pause to wrap my arms around the whole way. Many of these trees are older than me, older than anyone alive, older than this nation. I was taught to respect my elders. Why should I not extend that respect and love to these chestnut oaks, these hickories, these hemlocks?

Shouldn’t I teach my children to respect their elders in the same way?

As Benjamin and I reached Knobby Rock at the top of our climb 2000 feet above sea level, we gazed out at the seemingly vast untouched wilderness. I knew that we were part of that “holy remnant” as well – the small percentage of people who do care about these places. Who are proud to be called “tree huggers.” Who take it as their holy purpose to carry the memories of these places, and to encourage the sacred trust of these lands for the next generation.

I contend that protecting these wild places is what will truly help make America great again.

My husband and I are teaching our children that protecting these natural lands is part of our faith, our heritage, and our duty as patriotic citizens. I invite you to be part of this “holy remnant.”

To learn more about Kentucky Natural Lands Trust, including how you can donate or volunteer, visit: http://knlt.org/.

Leah D. Schade is the Assistant Professor of Preaching and Worship at Lexington Theological Seminary (Kentucky) and author of the book Creation-Crisis Preaching: Ecology, Theology, and the Pulpit (Chalice Press, 2015).

Twitter: @LeahSchade

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/LeahDSchade/.

Read Leah’s poem with more pics from Blanton Forest: Nature’s Last Gold is Green: Autumn Tribute to Frost

More posts about teaching children to know about climate change, and to cherish and protect nature:

Dar Tellum: 1970s Children’s Book about Climate Change

Children’s Sermon Ideas for Earth Day

Welcoming Children into God’s Creation: 4 Things You Can Do Now

Healthy Trees, Healthy People: Why Citizen Scientists Are Needed as Climate Changes