All the anguished cries for mercy, all the urgent messages to come quickly, all the despairing and forlorn sobs we hear on the lips of different people in the Gospels—lepers, agonized parents, desperately ill, friends of sufferers, frightened fishermen, hopeless beggars, grieving mothers, heartbroken sisters—all of them are echoed in Gethsemane on the lips of Jesus. He becomes the anguished one, the desperate one, the one imploring for mercy.

He knows the distress and the pleading for a different outcome than the one he faced. He knows the grinding difficulty of wanting one thing and receiving another. I even hear Martha’s frustration with Mary in his chiding of the sleepy disciples who could not pull it together enough to stay awake with him.

Jesus’ years of generous divine grace—healing lepers, and raising from the dead, and restoring sight, hearing, and even posture, feeding, and teaching, and soothing, and rescuing—all come down to these hours of “unanswered” prayer, hours when all the tortured cries of humanity to God over the centuries, cries that all too often seem to fall on deaf ears, culminate in God himself being denied what he most wanted.

Except that it wasn’t what he most wanted. He actually got what he most wanted.

Jesus had done the hard work of ordering his passions, a work to which we are each called. The desert fathers spoke extensively about our unruly passions, the desires of our hearts and bodies and minds that yank us around and make so many demands. Unlike some Eastern religions, however, Christianity does not teach us to discard our passions or learn to ignore them. We’re not called to be fat, happy little buddhas blissfully seeking to escape the suffering that desire brings; rather, we’re called to order our desires, to bring them into alignment with a deeper desire, a greater hope, a larger vision.

Scripture doesn’t teach us not to want all that is good and rich and wonderful; it teaches us to love the One who gives us these things and to desire him. It teaches us that all these other wants are best satisfied in the goodness God has designed for us.

Seventeenth-century author Brother Lawrence and his teaching on practicing the presence of God have encouraged so many to experience what the scriptures teach to be true: “You hem me in, behind and before.” “When my spirit is faint, you know my way.” “You are with me, your rod and staff they comfort me.” “In him we live and move and have our being.” “God who is over all and through all and in all.” “Abide in me as I abide in you.” “Your life is hidden with Christ in God.”

But it’s not magic. Brother Lawrence didn’t know the abracadabra of practicing the presence. It was a long, long struggle to enter into this experience, a ten-year training of his mind and soul and will to recognize that indeed there is no where God is not. No. Where.

Divine absence is a lie. Awareness and welcome of God’s presence is the great call of scripture, and blindness, hiding, and indifference are the sicknesses of the soul. We don’t “conjure up” his loving and wise presence; we recognize it; we welcome it. We breathe it in and out. We turn our faces into his great embrace.

And so Brother Lawrence writes:

The difficulties of life do not have to be unbearable. It is the way we look at them–through faith or unbelief–that makes them seem so. We must be convinced that our Father is full of love for us and that He only permits trials to come our way for our own good.

Let us occupy ourselves entirely in knowing God. The more we know Him, the more we will desire to know Him. As love increases with knowledge, the more we know God, the more we will truly love Him. We will learn to love Him equally in times of distress or in times of great joy.

This kind of experience genuinely lived out will be a series of Gethsemanes, some great and some small. It consists of one choice after another, a constant reordering of desires. It sounds agonizing, and sometimes it is, but it is mostly a natural result, as Brother Lawrence describes, of a new, compelling, and growing love for God.

Love tends to change things, of course. We fall in love with another, and very quickly we find ourselves reordering our desires, our careers, our habits, and our tastes. We have a child, and then we proceed to do things we’d never imagined possible, choosing acts of patience, self-sacrifice, generosity, humble service.

As our love for God and confidence in him grows—our captivation by his abundant goodness and faithful love for us—we increasingly embrace his will and believe that indeed, it is wonderful and desirable, no matter how painful the circumstances within which it sometimes comes.

Thus we’re back to Gethsemane, the clash between Jesus’ natural human desires and his love for and confidence in God; we watch him experience the real and present threat that God’s will implies to his existential well-being. We see the agonizing disconnect that he feels, that disconnect that we, too, feel (sometimes all day every day, I must admit).

Only Jesus’ love for the Father enables him to cling to the greater desire, the greater trust, the greater hope, and yield entirely his prayers for deliverance.

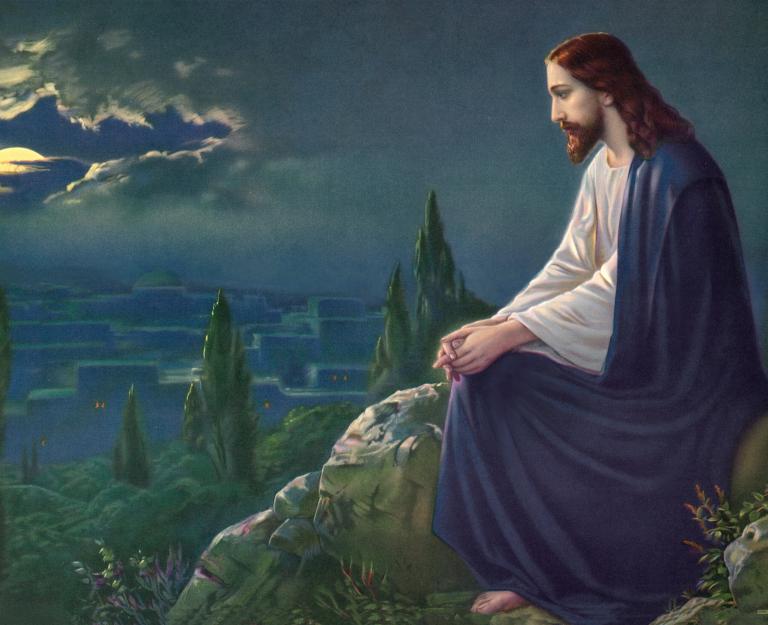

So many artistic depictions seem to erase the agony of the Garden. They seem so committed to protecting Jesus’ quiet submission that they make it look easy.

Here, for example, is Josef Untersberger’s vision of the scene.

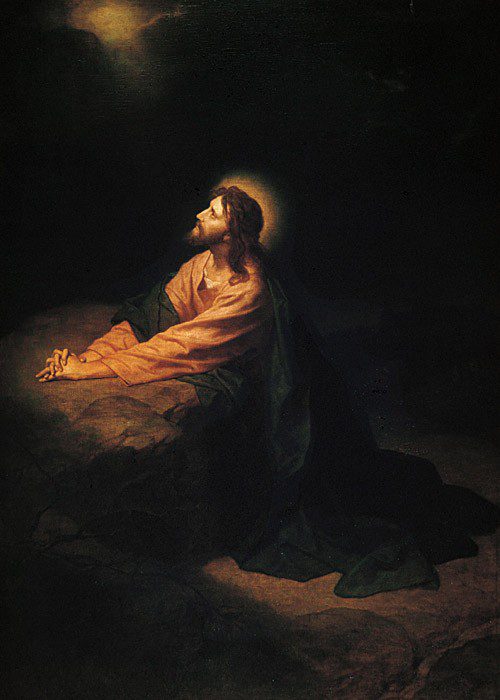

And here is Heinrich Hofmann’s iteration.

To me, in these depictions Jesus looks so quiescent, so passive and resigned. “[Sigh…] Okay, Father, if you say so…”

Yet the scriptures talk about him anguishing to the point of sweating blood. Or what about this description of the scene? “In the days of his flesh, Jesus offered up prayers and supplications, with loud cries and tears, to the one who was able to save him from death…” (Heb 5.7). Loud cries and tears—you and I both know what that looks like. It isn’t pretty. Eyes swollen, face contorted, hair disheveled, sweating, panting. Mark tells us he was distressed and agitated. I know distress and agitation.

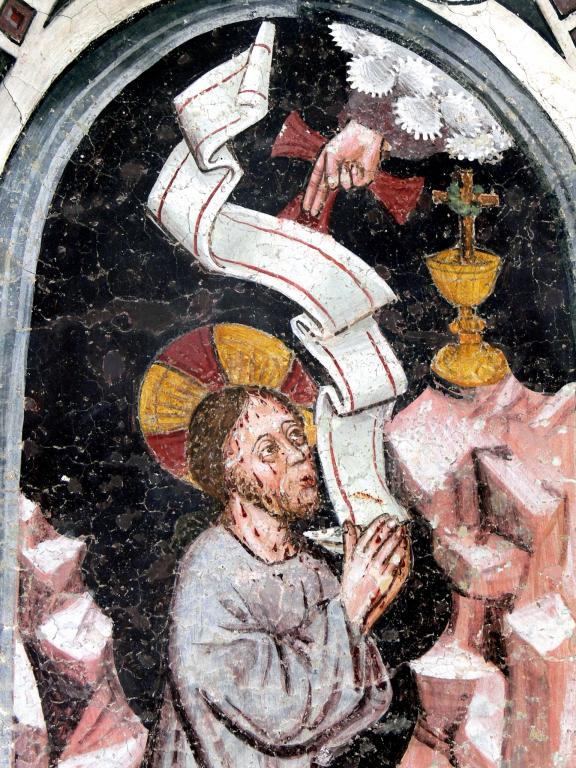

This, by 15th-century artist Leonhard of Brixen, seems truer to me–Jesus, in a posture of humility, directing all his hope to the One who alone understood what was being asked of him, sweating blood, face in anguish, struggling to accept, yet begging for a way out. Nevertheless, that hand coming down, it isn’t only a hand of authority and direction, it’s a hand of strength and compassion.

Luke tells us that God sent an angel from heaven to appear to him and give him strength. The Father wasn’t just telling Jesus to gut it out, to bully up and be a man and do the job he was being asked to do. When we think this way, we have lost our vision of the Trinity, the Three who together conspired to do all that was necessary to make right all that was wrong. The Father’s heart was there in Gethsemane, present, near, warm. William Blake evokes both the agony and the divine love.

We, too, return to Gethsemane every time we face the inner conflict between what we so deeply want and what God sends our way or allows us to encounter, and if you’re anything like me, you’ll have multiple Gethsemane moments daily as you order your desires. Breath by breath, keeping Jesus company in his Gethsemane, knowing his presence in ours.

Confidence in God’s goodness and love for him help me stifle the angry word, accept the inexplicable delay, forego the credit or attention I crave, do the dishes I didn’t dirty, give what I’d rather spend on myself.

Confidence in God’s goodness and love for him sustain me in my memories of great loss, my present anxieties and seemingly unbearable stresses, my uncertain future.

Confidence in God’s goodness and love for him keep me upright at the graveside, fortify me in the burdens of hard relationships, steel me for humiliation, comfort me even when he is silent.

Confidence in God’s goodness and love for him release me from grasping at what I so desperately want, not dissolving those wants at all or feeling shame for having them, but taking them captive to a greater desire, a deeper need.

George MacDonald, the great 19th-century Scottish preacher and fantasy writer, puts it this way:

The main idea in God’s idea of prayer is the supplying of our great, our endless need—the need of Himself. The good of all our smaller and lower needs lies in this, that they help to drive us to God. Hunger may drive the runaway child home, and he there may or may not be fed at once, but he needs his mother more than his dinner. Communion with God is the one need of the soul beyond all other needs.

The good Lord knows I need a lifetime of practicing Gethsemane to really learn this.