Coders play a glorified role in our society. They are makers-of-worlds. To see your code spring to life is a wonderful, exhilarating experience. Coders know what this feels like. This creative power inspires altruism in the hacker ethic. It also contributes to idealistic thinking that can slide into techno-utopianism. In previous posts, we have celebrated the beauty of this creativity, and noticed the risk of hubris that sprouts from it.

With power comes moral responsibility. The root problem is sin, of course. If you don’t like that word, then you might try some of these: brokenness, bad behavior, malevolence, harmfulness, selfishness, or evil. But I would suggest that sin really is the right word, because it names the inescapable, inherent reality of corruption woven into the very fabric of human society.

There’s no getting around the reality of sin. If we buy into the illusion that we can solve all our problems with smarter AI’s, better code, and safer robots, we are kidding ourselves. Ventures guided by the hubris of techno-utopianism will crash upon the shoals of sin, leaving shattered ethics and scandals in their wake, as Facebook’s ever-expanding string of scandals makes clear.

The Vandalism of shalom

Sin is a religious concept, not just a moral concept. The idea that we can “fix” every problem with better code is idealistic. It ignores the painful reality that sin lingers in human hearts and finds a way to corrupt infrastructures. This is the moral quagmire in which Facebook remains stuck, due to Mark Zuckerberg’s idealistic “focus on code as the solution to every problem” (McNamee 2019, p. 64). Such idealistic thinking never admits the possibility that the business model itself might be broken (or “tainted by sin”), because there is no recognition of sin in the first place.

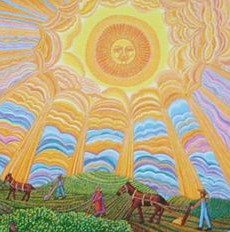

In biblical context, sin is the “vandalism of shalom” (Plantinga 1995). Shalom also is a religious concept: it is what life looks like when relationships move in mutual directions of righteousness—it is “God’s design for creation and redemption” (Plantinga 1995, p. 13).

In the absence of spiritual awareness for sin and shalom, morality defaults to consideration of whether a given choice will support or subvert the business plan. “Good” and “bad” are reduced to calculated effects on expected outcomes. Game theory dominates the decision tree. Gamification becomes the accepted wisdom, which is tragic for business ethics. Instead of defining the purpose of the business in terms of serving societal shalom (a spiritual reality), purpose is defined in terms of what serves the corporation.

Sin is the “bug” that breaks idealistic visions

Zuckerberg envisions his social network as something akin to a global church that will connect the world’s people and provide “moral validation that we are needed and part of something bigger than ourselves.” This sounds good, but the thinking is circular—these goals are defined in terms of what serves Facebook. In the same vision letter, Zuckerberg suggests that Facebook will build a “global safety infrastructure” that will enable the global community “identify problems before they happen.” These are lofty aims. The intent may be admirable, but the worldview in which these plans unfold is blind to the spiritual reality that the social network itself can be subverted by sin and become a tool for the vandalism of shalom. To posit the social network as a global source of moral validation connecting everyone to a greater reality is tragically idealistic. It is hubris on an almost unimaginable scale.

In this worldview, ethical problems are not due to sin, but rather are seen as transitory “bugs” that need to be fixed. This sort of idealistic thinking places inordinate trust in the goodness of the corporate mission, because it fails to recognize the inherent risks of vandalism to shalom. Any corporate culture built on such hubris is likely to grow insular and to shut out dissenting opinions that might bear witness to the realities of sin.

Charles Taylor has a name for these circular, self-referential mindsets: “closed world structures” (CWS). An idealistic business vision can function as a CWS. It ‘naturalizes’ a certain view on things, thus making it impossible to diagnose the corrupting influences of sin present in infrastructures and the people building, using, and profiting from them. The CWS permits no foothold for external critiques. There is no vantage from which to observe and diagnose why things are not the way they are supposed to be.

The vandalism of shalom is a particularly acute problem in the realm of social media. Without a spiritual understanding of shalom in human relationships, the vandalism can go misdiagnosed and untreated. Facebook’s infamous “massive emotional contagion” experiment of 2014 shows how easily the social network can be used to damage shalom. In this instance, Facebook researchers deliberately manipulated users’ newsfeeds to induce mood swings. This demonstrates a serious lack of respect for the freedom and well-being of the unwitting Facebook users caught up in it.

The power to monetize people’s attention span, habits and relationships poses a problem of tragic importance for social media platforms, and the applications, news sources, influencers and advertisers who use them. Self-referential visions of technology platforms tend to reduce human relationships to data. This is the essence of the “surveillance capitalism”, as Zuboff (2019) defines it—“a new arc” in civilization that aims to “modify the behavior of individuals, groups, and populations in the service of market objectives.”

Institutional sin, shielded by insular thinking, may be the most nefarious problem with idealistic visions. As Plantinga says, “Sin burrows into the bowels of institutions and traditions, making a home there and taking them over” (p. 75). Not only does sin pervert the function of institutions, but it also corrupts the norms and habits which comprise interpersonal communications and relationships. Institutional sin diverts awareness and intentions away from shalom—“God’s design for creation and redemption.”

Diagnosis brings hope for a cure

Plantinga has it right when he says, “a diagnosis of sin and guilt allows hope.” (p. xii)

In facing the reality of sin, we find hope for a cure. Indeed, the promise of the cure is assured: The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it [John 1:5].

Proper diagnosis of the problem allows us to design and build mechanisms into business strategies that reject the idolatry of self-referential morality and idealistic thinking. There are ways to use these technologies wisely. In future posts, I shall continue to unpack this thesis, express reasons for hope, and suggest some constructive steps forward.