It happens every year around this time, so now seems as good a time as any to remind everyone that the popular myth now making the rounds again just isn’t true.

In case you missed it, here’s what countless people believe and share on social media:

“The Twelve Days of Christmas” was written in England as one of the “catechism songs” to help young Catholics learn the tenets of their faith – a memory aid, when to be caught with anything in writing indicating adherence to the Catholic faith could not only get you imprisoned, it could get you hanged, or shortened by a head – or hanged, drawn and quartered, a rather peculiar and ghastly punishment I’m not aware was ever practiced anywhere else. Hanging, drawing and quartering involved hanging a person by the neck until they had almost, but not quite, suffocated to death; then the party was taken down from the gallows, and disemboweled while still alive; and while the entrails were still lying on the street, where the executioners stomped all over them, the victim was tied to four large farm horses, and literally torn into five parts – one to each limb and the remaining torso.

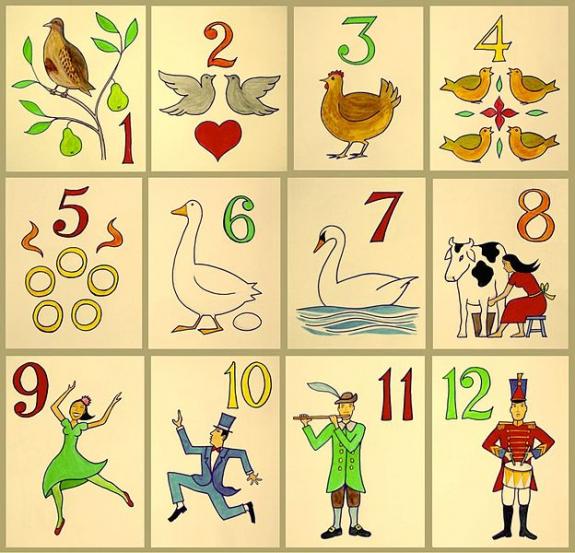

The songs gifts are hidden meanings to the teachings of the faith. The “true love” mentioned in the song doesn’t refer to an earthly suitor, it refers to God Himself. The “me” who receives the presents refers to every baptized person. The partridge in a pear tree is Jesus Christ, the Son of God. In the song, Christ is symbolically presented as a mother partridge which feigns injury to decoy predators from her helpless nestlings, much in memory of the expression of Christ’s sadness over the fate of Jerusalem: “Jerusalem! Jerusalem! How often would I have sheltered thee under my wings, as a hen does her chicks, but thou wouldst not have it so…”

It goes on, explaining the symbolism of the different gifts.

Now, the rest of the story:

Two very large red flags indicate that the claim about the “secret” origins of the song “The Twelve Days of Christmas” is nothing more than a fanciful tale, similar to the many apocryphal “hidden meanings” of various nursery rhymes:

- There is absolutely no documentation or supporting evidence for this claim whatsoever, other than mere repetition of the claim itself.

- The claim appears to date only to the 1990s, marking it as likely an invention of modern day speculation rather than historical fact.

Moreover, several flaws in the proffered explanation argue compellingly against it:

The key flaw in this theory is that the differences between the Anglican and Catholic churches were largely differences in emphasis and form which were extrinsic to scripture. Although Catholics and Anglicans used different English translations of the Bible (Douai-Reims and the King James version, respectively), all of the religious tenets supposedly preserved by the song “The Twelve Days of Christmas” (with the possible exception of the number of sacraments) were shared by Catholics and Anglicans alike: Both groups’ Bibles included the Old and New Testaments, both contained the five books that form the Pentateuch, both had the Four Gospels, both included God’s creation of the universe in six days as described in Genesis, and both enumerated the Ten Commandments. A Catholic might need to be wary of being caught with a Douai-Reims Bible, but there was absolutely no reason why any Catholic would have to hide his knowledge of any of the concepts supposedly symbolized in “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” because these were basic articles of faith common to all denominations of Christianity. None of these items would distinguish a Catholic from a Protestant, and therefore none of them needed to be “secretly” encoded into song lest their mention betray one as a Catholic.Conversely, none of the important differences that would obviously distinguish a Catholic from a Protestant is mentioned here. A Catholic would have good reason not to possess or reveal anything that would indicate his allegiance to the Pope or his participation in the sacrament of penance (also known as Confession), but nothing of that nature is encapsulated in the explanation of the symbolism supposedly to be found in “The Twelve Days of Christmas.”

If “The Twelve Days of Christmas” were really a song Catholics used “as memory aids to preserve the tenets of their faith” because “to be caught with anything in writing indicating adherence to the Catholic faith could get you imprisoned,” how was the essence of Catholicism passed from one generation to the next? The mere memorization of a song with coded references to “the Old and New Testaments” in no way preserves the contents of those testaments. How was this preservation of content accomplished if possessing the testaments in written form was forbidden? Did Catholics memorize the entire contents of the Bible? Obviously not, and there was no reason to do so: Since Catholics and Anglicans both used the Old and New Testaments, possessing their contents in written form did not expose one as a Catholic, and thus there was no need to cloak common Biblical concepts through the use of mnemonic devices. There was no reason why “young Catholics” could not be openly taught about the Four Gospels, or the eleven faithful apostles, or the Ten Commandments.

And note this:

It is possible that “The Twelve Days of Christmas” has been confused with (or is a transformation of) a song called “A New Dial” (also known as “In Those Twelve Days”), which dates to at least 1625 and assigns religious meanings to each of the twelve days of Christmas (but not for the purposes of teaching a catechism). In a manner somewhat similar to the memory-and-forfeits performance of “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” the song “A New Dial” was recited in a question-and-answer format.

Wikipedia, meanwhile, has an interesting analysis of what the 12 gifts represent, concluding:

According to The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, “Suggestions have been made that the gifts have significance, as representing the food or sport for each month of the year. Importance [certainly has] long been attached to the Twelve Days, when, for instance, the weather on each day was carefully observed to see what it would be in the corresponding month of the coming year. Nevertheless, whatever the ultimate origin of the chant, it seems probable [that] the lines that survive today both in England and France are merely an irreligious travesty.” (It is also worth noting that exactly 364 gifts are given, one for each day of the year besides Christmas.)

In 1979, a Canadian hymnologist, Hugh D. McKellar, published an article, “How to Decode the Twelve Days of Christmas” in which he suggested that “The Twelve Days of Christmas” lyrics were intended as a catechism song to help young Catholics learn their faith, at a time when practicing Catholicism was criminalized in England (1558 until 1829). McKellar offered no evidence for his claim. Three years later, in 1982, Fr. Hal Stockert wrote an article (subsequently posted on-line in 1995) in which he suggested a similar possible use of the twelve gifts as part of a catechism. The possibility that the twelve gifts were used as a catechism during English and Irish Catholic penal times was also hypothesized in this same time period (1987 and 1992) by Fr. James Gilhooley, chaplain of Mount Saint Mary College of Newburgh, New York. Snopes.com, a website reviewing urban legends, Internet rumors, e-mail forwards, and other stories of unknown or questionable origin, also concludes that the hypothesis of the twelve gifts of Christmas being a surreptitious Catholic catechism is incorrect. None of the religious concepts allegedly symbolized by the enumerated items would distinguish Catholics from Protestants, and so would hardly need to be secretly encoded.