Year C + Proper 13 + Luke 12:13-21

When I was about nine years old, I started amassing an extensive collection of comic book action figures for a kid my age. For several years, I devoted every dime of my weekly allowance to buying these figures, and eventually I collected them all — from Capt. America and Deadpool to Wolverine and Daredevil.

My childhood friends and neighbors also loved these figures, but unlike them I would never bring mine over to their houses after school to share in epic plastic superhero adventures. In fact, I never even played with my figures and instead kept them in perfectly unopened packages and meticulously displayed them on my bedroom wall. My neighborhood friend Jake was always a little dumbfounded and frustrated with me about it because he never understood my plan to one day as an adult sell these collectible figures for a massive financial windfall.

As you might have guessed that my early retirement plan never really panned out. So for more than 20 years, I have been stuck with dozens and dozens of comic book figures in storage that I both couldn’t bear to part with and still couldn’t imagine opening and ruining any potential value left in them.

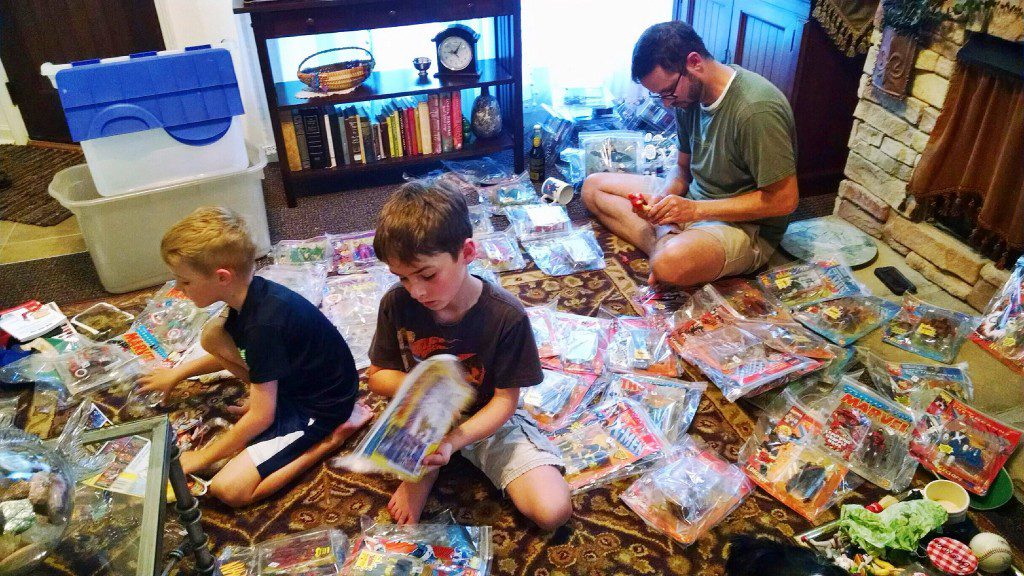

But when my own kids started to become interested in superheroes, I did something I never imagined I would. I learned to share my toys. I pulled out the boxes and boxes of figures from storage, and we had a little party of sorts, opening up figure after figure together and going on imaginary superhero adventures. It was a small, but meaningful moment where my past met my present and future, where I shared a part of my childhood with my own kids. Watching them with those toys brought me more joy and connection than they ever did all those years while displayed on my wall.

I share this story with you because if I’m honest, there really is a part of me that identifies with the rich man in today’s gospel story, and I’d wager I’m not the only one. In fact, there’s a good argument that any time we read a story about a wealthy person in the gospels, we ought to listen closely. After all, we live not only in the wealthiest country in the world but arguably the wealthiest nation in human history. Despite this abundance, we live in a state where 1 in 4 children don’t have enough to eat every day. But with all the understandable stresses of life, work, and family, it’s often easy not just to forget about the reality many of our neighbors live in but to never even have it cross our minds. We’re so isolated from it, we simply don’t see it.

And ultimately, that’s what I think this parable is about. It’s a story about a rich man who is so isolated from his community he can’t see beyond his own small, insular reality. To me, that’s the most striking element in this parable, not how much this man has but just how he’s missing. At first glance, we might not notice the huge gaps in this story, but Jesus’ listeners — many of them peasants, day laborers or subsistence farmers for whom hunger was a daily threat — would have immediately noticed what was missing.

Because they are the ones missing from this rich man’s reality, and their unspoken presence haunts this parable like ghosts.

Think about how differently this parable would sound if we listened to it from the perspective of a laborer or farm worker in Jesus’ audience.

To the rich man, the land magically and unexpectedly produces an exceptional abundance out of nowhere. But many of Jesus’ listeners would have known that the land doesn’t just produce a crop much less an abundance on its own. It required months of labor and dozens of workers to plant the fields, tend the crops, and harvest it. The rich man then muses to himself about what he will do with all this food because he doesn’t have room to store and he certainly can’t eat all of it. So he decides to build a bigger barn. But Jesus’ listeners knew exactly where this man should have invested God’s abundance provided through the land — into the empty stomachs of the people who harvested it in the first place, as required by Jewish tradition.

Imagine the rueful irony of a rich man hiring workers and day laborers to tear down and build a bigger barn to store an abundance of food reserved only for one, all the while they themselves didn’t have enough to eat.

It’s not that storehouses were bad. In fact, they were a prudent necessity in a region given to drought, famine, or crop failures. The problem was that in the small, agrarian villages typical in this region, storehouses were meant not for the exclusive use of one family, let alone one person. They were a critical safety net for entire community. Since the land was ultimately a gift and inheritance from God, its abundance was meant for all the people of God, not just a select few.

Time and again, prophets called upon Israel to be better, more faithful stewards of God’s gifts, especially for those in need, the widow, the orphan, the poor, or the foreigner. Set in the Jewish context, the parable contrasts starkly with other examples of righteous men who used wealth according to God’s design. Like Joseph who built massive storehouses for Pharaoh in Egypt to distribute grain and food to the hungry during a famine. Like Abraham who, according to tradition, used God’s blessing of wealth to build a house in which to welcome, shelter, and feed travelers. He could have even taken a cue from God who fed the Israelites with abundant manna in the desert but warned that if they gathered more than they needed, the food would turn rancid and putrefy.

Wealth was a blessing, but only if it was shared with others. If it wasn’t, it became a curse. Wealth was meant to build up, protect, and enrich the community, not to isolate us from it.

And perhaps that’s the most dangerous kind of greed, a kind of greed that has less to do with money and more to do with using money to wall ourselves off into silos from others. It’s the greed of self-reliance and bootstraps which fools us into believing we don’t need each other and have no responsibility to each other. Until the point comes when we like the rich man simply no longer see our neighbors at all.

Nowhere, though, is this rich man’s alienation so painfully clear than in his decision to celebrate his abundance and newly completed storehouse. He throws a party of sorts, but has no one to invite but himself. Throughout Jesus life and parables, images of feasting and revelry were symbols of the abundant, divine feast of God to which all are invited to come. But with the rich man, we have a tragically twisted version of this banquet. It’s a reverse Eucharist, a feast without great thanksgiving to God and without a community gathered to share in the abundance.

This is a portrait not of an evil man, but of a deeply sad and alienated one. He’s in the cruel and unusual prison of solitary confinement of his own design, an outcast of his own making.

When God comes that very night, the night of his lonely feast, all is revealed as God declares him a fool for how he’s spent his life. It’s tempting to think of this as God’s ultimate condemnation of the man, but I can’t help but wonder if it’s God’s final act of mercy and compassion, the only way he can at last reach the man. God had provided him abundance through the land, a good gift that should have rooted him in his community and connected him with his neighbors in need. It should have brought him into deeper relationship with God and his faith through thanksgiving. That abundance could have saved him from himself and provided his life with meaning larger than his own tiny existence. But instead it only pushed him deeper into alienation.

So while God does show up and demand his soul, it’s a bittersweet ending in a way because it’s also the first time in the parable that he finally hears a voice other than his own. It’s the first time perhaps in his life the rich man is finally connected to something bigger than himself.

In the end, Jesus reminds his listeners to focus on being rich toward God not in the abundance of possessions. To do so, Jesus asks us to enter into and invest in our community, to open up our storehouses whatever they may hold, even if it’s just a bunch of action figures, so we can stop living in silos and better share our lives together. In doing so, while we might never be superheroes, maybe, just maybe we can embark on a holy adventure together and be transformed by it.

Image Credit: USDA