Easter 4C — John 13:31-35 — Lectionary Reflection

One of the curious things about Jesus’ new commandment he gives to the disciples is that it doesn’t really seem all that new.

It’s something that frustrates me every Maundy Thursday when we read this story, this idea that serving others and loving others is somehow a brand new idea no one had ever thought of before Jesus came along. Loving one another isn’t an earth-shattering new reality. You can find that command, or versions of it, throughout the Hebrew Scriptures. It’s not really all that new. It sounds rather orthodox and traditional.

But for some reason, it’s come to be known as a new commandment.

I’m not sure I buy it entirely.

So as I was re-reading the story this week, it struck me that for all of our Maundy Thursday ritual, the context of this commandment isn’t really the foot-washing. Instead, it’s the revelation of Judas’ betrayal and his abrupt departure from the group during dinner.

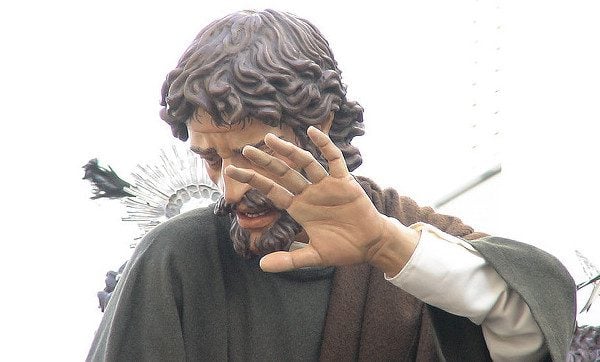

In this story, that revelation greatly disturbs and troubles Jesus. He is hurt, wounded that one of his inner circle is betraying him. In the context of heart-rending betrayal Jesus gives his new command, to love each other and to be known as Jesus’ disciples by their love for each other.

Even their love for the one who betrayed.

It’s a reminder to his disciples that Judas was still one of them, one of the 12, despite his betrayal that would lead to Jesus’ brutal execution.

Essentially, in the moments after Judas’ betrayal is revealed, Jesus reminds the disciples of who they are and what they are to do. To love each other, no matter what, because that is the only way they can be identified as his disciples. It’s almost as if Jesus is reminding them, “I love Judas. Don’t forget what just happened. I washed his feet and broke bread with him, even though I knew what he was going to do. I still love him and welcomed him, my betrayer, to be one of us. It troubled me deeply. It hurt. But I did it. Now you have to do the same. Love Judas as I have loved you. Serve him as I have served you. That’s how people will know you are my disciples: if you love Judas.”

Now that isn’t just a groundbreaking commandment. It’s an incredibly difficult one to put into practice. It’s popular to talk about loving our enemies in terms of our state’s enemies — people like Osama bin Laden. And, it’s not that difficult to “love” a person we’ve only seen in images on television because it doesn’t cost most of us anything. I can write an eloquent prayer for the repose of the soul of bin Laden but spend the rest of my day swearing at drivers who cut me off or sulking for days after my spouse and I have a fight. Not that I’ve ever done either of those in my life, of course.

But it’s much harder to think about loving our enemies in terms of loving those who have wounded us. It’s much trickier to think about how we are to love those who know where our vulnerabilities are and at times exploit them. It’s almost unfathomable to think about loving our betrayer. And if that intellectually is difficult to consider, it’s even harder to put into practice what love actually looks like when life’s messiness obliterates stark black-and-white, right-and-wrong moral zones.

There’s no blueprint for how to do this. I don’t think we can even say for certain we’d love our enemies until the moment we are actually called to do so. But I’m convinced the disciples figured out a way to do it in the gospel of John. They might have messed up and misunderstood most everything else in the gospel, but I think they actually got this commandment right.

Because, in John, Judas came back to be counted as one of the Twelve.

It’s a small detail I’ve always overlooked, but I don’t think it’s insignificant. After the resurrection, only John’s gospel still calls the disciples the Twelve rather than the Eleven.

In Luke-Acts, the women return to “the Eleven” to report the resurrection, and the disciples later elect Matthias to replace Judas.

In Matthew, Judas hangs himself and toward the end, “the Eleven” go to Galilee.

In Mark, Jesus appeared “to the Eleven.”

But in John, Jesus appears to all the disciples except Thomas, who was one of “the Twelve.” It’s a remarkable, arresting phrase to read after the resurrection in light of the other gospels and to realize that in John, no one is missing. Judas hasn’t fallen headlong in a field, hung himself, or just disappeared from the story. In John, they are whole. They are still Twelve disciples, not Eleven.

It’s a complete rewriting of the gospel record and of Judas’ story. It’s an alternate ending, where Jesus really does keep his promise that he would not lose even one given to him.

There’s no big fanfare of forgiveness or reconciliation. No huge summit about how it all went down. But someone Judas was lost and then he was found. He’s just there, in the background desperately happy to be there, relieved he’s not bleeding out in a field, swinging from a rope in a field, or completely erased from the resurrection. Because the odds for reconciliation and forgiveness are stacked against him. Three-quarters of the time, he winds up dead or lost. But this one miraculous time, there is quiet, unassuming forgiveness done behind closed doors. This one miraculous time, Judas lives.