This is a continuation of the exchange documented in my post, Problem of Evil & of Good: Great Dialogue w Agnostic (6-17-21). The words of “axelbeingcivil” (from my combox) will be in blue.

*****

Alright, here we go! This is gonna take some time and effort…

I don’t want to turn this into a mega-quote-fest, so I’m going to try and break this down into several broad categories of response. There’s multiple threads to this discussion now and they all deserve a response, but they all have their own unique aspects.

Broadly, I’d frame these things as…

1. Permissive vs. Perfect Will

2. The actions of Satan specifically

3. Libertarian free will (I am probably going to cover this discussing point 1)

4. Good in a godless world

Permissive vs. Perfect Will

So, before I go any further, I need to just clarify terms here as to what is being talked about. If I understand the concepts correctly, Perfect Will represents what God “wants” to happen. That is, if all the universe worked flawlessly and without failure, God’s perfect will is precisely what would happen but, according to the argument, because of free will, things don’t go according to the grand plan.

That’s right. God can’t control free will to mold it into His perfect will, or else it would cease to be free will. But He can work around and with it and bring about the best outcome, given free will: at least for His followers. Romans 8:28 (my favorite verse in the Bible) states: “We know that in everything God works for good with those who love him, who are called according to his purpose” (RSV). God also has to work around our Cosmic Rebellion, which Christians call “the fall” or “original sin”; and our continuing predisposition towards sin (concupiscence). He does so, but that is His permissive, rather than perfect will.

Permissive Will, therefore, is the result. That is, God allows us to act upon our free will, regardless of the consequences to ourselves or others, because free will creates some kind of moral value. That is, God could’ve made us robots who automatically and always love and obey, but didn’t because it’d nullify the value of any good that we do.

Correct. Would you prefer to be a robot rather than a free agent who is truly free?

Now, of course, there are times where God does intervene. Miracles, prophets, etc.

As a rare exception to the usual norm and as an act of mercy . . .

These, of course, shun the Permissive Will, as God imposes the divine will directly,

It’s hardly “imposition” if we like the results. The recipient of a miracle would say, “God can ‘impose’ that type of will on me whenever He likes, if I am healed of blindness or have a demon cast out of me, or am cured of cancer!”

but I don’t think your argument requires God to be in any way consistent with when they do or do not apply Permissive Will.

We are too limited in our perspective to even fully understand what “consistency” means in an omniscient, all-benevolent Being. Let me submit an analogy if I may. We were changing our oldest granddaughter’s diaper yesterday (we’re babysitting her for a week) and she was putting up a tremendous fuss. No doubt she thought this was “torture” and a huge inconvenience (perhaps even embarrassment: who knows?). But from our far more advanced vantage-point we know it was absolutely necessary and that to not do it would bring about a diaper rash, making her far more miserable than she was during the “ordeal” of a diaper change.

Just like the baby, there are many things we can’t possibly comprehend about God, by the nature of the case. He’s infinitely greater in every way than we are. This is why He provided us with inspired revelation: to learn as much as humanly possible about Him.

You’ll forgive me for considering that arbitrary, though.

It’s not, in light of what I just wrote.

But, all that said, I do not consider the conception of a “Permissive Will” to be a moral defense here.

Humans engage in permissiveness too. Earlier, you used the example of you letting your daughter go out and party. There’s a possibility that doing so may lead to questionable behaviour but, in the long run, you allow it because the experience of making her own decisions is worth the risks entailed there.

On the other hand, if your daughter showed you a handgun and told you she was off to murder the neighbour… You might be inclined to try and stop her! You’d recognize that the benefits of her freedom are significantly outweighed by the long-term harm she is almost certainly about to do.

God simply can’t intervene (as our infinitely greater Creator) every time an evil act is going to occur. It’s not the same as a parent and a daughter. Every analogy of human beings to God has its limitations. This is what I mentioned last time. God is on a different plane than we are. I speculated about a world in which God intervened to prevent every particular act of evil in my longest and most in-depth treatment of this issue:. I was talking more about natural disasters and calamities, but the same reasoning could easily be applied to human-produced acts of evil:

It is said that God could and should have performed many more miracles than Christians say He performs, to alleviate “unnecessary” suffering. But this is precisely what a natural world with laws and a uniformitarian principle precludes from the outset. How is it that the atheist can (in their hypothetical theories and arguments against Christianity) imagine all sorts of miracles and supernatural events that God should have done when it comes to evil and the FWD [free will defense]? “God should do this,” “He should have done that,” “I could have done much better than God did,” . . .

Yet when it comes to natural science (which is precisely what we are talking about, in terms of ”natural evil”), all of a sudden none of this is plausible (barely even possible) at all. Why is that? Legions of materialistic, naturalistic, and/or atheist scientists and their intellectual followers won’t allow the slightest miracle or direct divine intervention (not even in terms of intelligent design within the evolutionary hypothesis) with regard to the origin of life or DNA or mammals, or the human brain or eye, or even unique psychological/mental traits which humans possess.

Why would this be? I submit that it is because they have an extreme reluctance to introduce the miraculous when the natural can conceivably explain anything. They will resist any supernatural intervention into biological processes till their dying breath.

Yet when we switch the conversation over to FWD all of a sudden atheists — almost in spite of themselves – are introducing “superior” supernatural options for God to exercise, right and left. God is supposed to eliminate all disease, even though they are inevitable (even “normative”) according to the laws of biology as we know them. God is supposed to transform the entire structure of the laws of physics, so no one will ever get a scratch on their face. He is supposed to suspend a bullet in mid-air so it won’t kill its intended target, or make a knife turn to liquid before it rips into the flesh of yet another murder victim.

In the world these atheist critics demand of God, if He is to be a “good” God, or to exist at all, according to their exalted criteria, no one should ever have to get a corn on their toe, or a pimple, or have to blow their nose, or have chapped lips. God should turn rocks into Jello every time a child is to fall on one. Cars should turn into silly putty or steam or cellophane when they are about to crash. The sexually promiscuous should have their sexual diseases immediately healed so that no one else will catch them, and so that they can go on their merry way, etc.

Clearly, these sorts of critics find “plausible” whatever opposes against theism and Christianity, no matter what the subject is; no matter how contradictory and far-fetched such arguments are, compared to their attacks against other portions of the Christian apologetic or theistic philosophical defenses. Otherwise, they would argue consistently and accept the natural world as it is, rather than adopting a desperate, glaring logical double standard.

In effect, then, if we follow their reasoning, the entire universe becomes an Alice in Wonderland fantasy-land where man is at the center. This is the Anthropic Principle! Atheists then in effect demand from God the very things they claim to loathe when they are arguing against theism on other grounds. Man must be at the center of the universe and suffer no harm, in order for theism to be true. Miracles must take place here, there, and everywhere, if theism is to be accepted as a plausible or superior alternative to atheism.

The same atheists will argue till they’re blue in the face against demonstrable miracles such as Jesus’ Resurrection. What they demand in order to accept Christianity they are never willing to accept when in fact it occurs to any degree (say, e.g., the healings performed by Jesus). God is not bound by human whims and fancies and demands. The proofs and evidences He has already provided are summarily rejected by atheists, one-by-one, as never “good enough.”

Atheists and other skeptics seem to want to go to any lengths of intellectual inconsistency and hostility in order to preserve their skepticism. They refuse to bow down to God unless He creates an entirely different world, in order to conform to their ultimately illogical imaginings and excessive, absurd requests for what He should have done. They’re consistent in their inconsistency.

By definition, the natural world entails suffering. One doesn’t eliminate that “difficulty” simply by resorting to a hypothetical fantasy-world where God eliminates every suffering by recourse to miracle and suspension of the natural laws He put into place.

In any event, the world as He created it did not originally involve suffering (nor will it in the future, for the redeemed). Man could have chosen to live in such a world, just as the unfallen angels did. They chose never to rebel. But man did, and having done so, now he wants to blame God for everything for which the blame in actuality lies squarely upon his own shoulders.

The natural world can’t modify itself every time someone stubs their toe or gets a sunburn. That would require infinitely more miracles than any Christian claims have occurred. With a natural world and natural laws, any number of diseases are bound to occur. One could stay out in the cold too long and get pneumonia. Oh, so atheists want God – if He exists – to immediately cure every disease that comes about? Again, the miraculous, by definition, is not the normative. It is the extraordinary, rare event. I might stay underwater too long, swallow water, and damage my lungs. I could fall while ice skating, bump my head severely and damage my brain. I might eat a poisonous mushroom, or get stung by a poisonous snake, etc., etc. That’s how the world works. It is not God’s fault’ it is the nature of things, and the things of nature.

In an orderly, uniformitarian, largely predictable natural world which makes any sense at all, there will be diseases, torn ligaments, colds, and so forth. The question then becomes: “how much is too much suffering?” or “how many miracles is God required to perform to be a good and just God?” At that point the atheist can, of course, give no substantive, non-arbitrary answer, and his outlook is reduced to wishful thinking and pipe dreams.

Materialistic evolutionists resist miraculous creation at all costs precisely because they think miracles are exceedingly rare. Christians apply the same outlook to reality-at-large. We say that miracles will be very infrequent, by their very nature (“SUPERnatural”). And that must be the case so that the world is orderly and predictable enough to comfortably live in, in the first place.

This is because we recognize that there’s a threshold of potential harm beyond which allowing someone to act is unacceptable. We, too, value the free agency of other human beings, but that value is not exceeded by a certain degree of harm to others.

If God intervened every time we wanted to commit evil, then it would soon be the total contravention of free will (unless He picked-and-chose when to intervene, which is arbitrary and unlikely). Since He values our free will, He can’t do that because it is directly contradictory and even God is subject to the laws of logic, which are the laws of reality and the real world.

But He does mold our will in due course, as we approach a never-ending future in either heaven or hell. In light of that, this is simply a necessary temporary state of affairs: like a child having to wear braces for five years out of a life of 70-80 years or more. My wife had to wear a back brace for a while in her teenage years (scoliosis). Had she not done so, she would be in a wheelchair today. We chose to rebel. It wasn’t God’s choice. He allowed it.

Likewise, we recognize that, when one has the power to intervene to halt such violations, but chooses not to, one is culpable to some extent for them. Not as much as the bad actor, generally, but the degree of culpability is usually proportional to the level of control they had over the situation and responsibility that they held. This ranges from a parent allowing a child irresponsible levels of freedom (eating nothing but candy and smoking cigarettes is not something a responsible parent lets a twelve-year-old do) to not reporting malfeasance to refusing to intervene in ongoing immoral behaviour. If a wealthy person allows a person to starve at their door, the Bible itself calls that person out as evil!

None of these analogical considerations overcome the factors of the Creator-creature relationship that I have been discussing, in light of free will. You need to address the arguments I have been making too.

To that end, we have to conclude that, since God has the power to intervene and chooses not to, they bear at least some of the responsibility for what happens.

What this argument amounts to, then, is the belief that allowing the unrestrained exercise of free will is more important than placing any kind of safeguard or abjuration against evil action.

I don’t think anyone, anywhere, ever has comfortably made that argument. There are always circumstances where, at a certain point, it becomes immoral not to intervene. There’s always murkiness and grey areas because humans are still human, but I would argue that most human beings recognize, for example, that the British were right to put a stop to the immolation of widows in India, even if their conquest and occupation was a selfish evil.

I do not see any benefit to history’s great atrocities, especially not to the victims of those atrocities, that would justify a lack of intervention. Moreover, there is a double crime, too, in that many of those atrocities occurred due to lack of knowledge on the parts of various human beings.

In summary, I don’t find that perspective at all persuasive.

God does overcome “grand evil” in many ways, through prayer, selected miracles, the particularities of circumstances and situations, etc. So the Christian would say, for example, that men (not God) caused World War II. God didn’t decide to start killing everyone different (the Nazis and the Japanese). But God could have (and we believe, did) help in any number of ways to defeat that evil, in assisting human beings to overcome it. Thus, we have a world where the Nazis didn’t prevail and predominate. Other evils still have to be opposed (terrorism, remaining Communism, sexism, racism, economic exploitation, slavery [which still exists], sexual trafficking, drug pushers, militant fundamentalist Islam, sexual immorality, etc.). God will help relatively good people to defeat those things, too, should they decide to do so.

There are all kinds of stories about World War II, where prayer had a marvelous effect, or where weather changes favored the Allies. I just saw a movie about D-Day (The Longest Day). It is a fact that Hitler took a sleeping pill and slept longer than usual on the morning of D-Day. Consequently, German generals couldn’t do things they thought were necessary to prevent the success of the invasion. Who’s to say that God didn’t put the thought into the mind of Hitler: “take a sleeping pill”? Hitler’s little nap could have changed the entire course of the war.

The best German general, Rommel, was in Germany celebrating the birthday of his wife on D-Day and so was a non-factor. God does intervene in rare exceptions with miracles. Likewise, He can choose to intervene in a more subtle, hidden way. Hitler made lots of dumb military decisions, like deciding to fight on eastern and western fronts simultaneously (which sealed his fate in retrospect).

So God does intervene through massive prayer (human beings freely expressing their desire for good to prevail over evil). He’s a caring, loving God. But He cannot on the other hand (due to free will and the laws of nature), always intervene against evil (for the reasons I have explained); nor is He obliged to do so. He made us free and able, for the most part, to decide to cease doing the evil that we so often choose to do, and to oppose the evil that others are intent on doing.

Your task, on the other hand, as always, is to tell us all why you casually assume that various things are wrong and evil in the first place. You have no objective basis for doing so, without God. And so, today, we have otherwise ethical people saying it is fine and dandy to allow a baby who survived an abortion attempt to starve to death on a table in a hospital, gasping for air and in agony the whole time. I say that is evil and barbaric; so does Christianity and the Bible and God. Millions now say it is perfectly acceptable behavior, along with the ongoing genocide of abortion itself: which is our equivalent to the extraordinary moral blindness of slavery in the 19th century.

Even the likely minority of atheists who agree these things are wrong have no real, objective basis to say why they think so. Their morality comes from men. Thus, seven men on the Supreme Court in America in 1973 thought it was morally permissible to kill children in the womb. That’s the atheist “standard”: those seven men. There are many other examples besides abortion. Evil people think the drug trade or sexual trafficking is perfectly fine, etc.

Satan, in specific

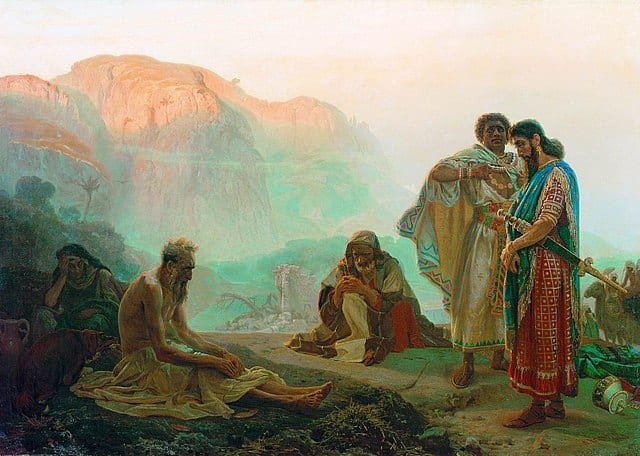

Satan’s a distinct and separate case here. I don’t think you reinforce your argument particularly well by referencing Job, in which God very specifically places Job – poor Job – into Satan’s hands.

That’s part and parcel of free will. In rebelling against God, human beings put themselves under the particular alternate influence of Satan, who had also rebelled as an angel. God allows this to take place. But there will be an end to it. And we know that because God, Who knows everything and is outside of time, told us so.

He does not let Satan kill him,

That’s the point. See, there was a limit, wasn’t there?

but allows Satan to torment Job in ways that are truly unimaginable for those who have not endured them; not merely the anxieties and fears of starvation and disease, but the loss of his wives and children, who are the essence of what makes life matter.

And in the end He restored Job’s fortunes. We’ve already been through this.

(As an aside, it’s entirely possible that Job was a slaveholder, so perhaps there’s a reason to not have too much pity on him, but I think anyone can appreciate that the loss of one’s family as a trauma regardless of the person in question.)

He suffered terribly. There is no doubt about that.

If the argument is that Satan acts freely, without God’s permission, Job is a bad example. Satan was explicitly given control by God.

He’s permitted to do so. Permissive will. It doesn’t portray God as saying, “I think it’s wonderful that you want to horribly torment Job! You have My blessing!” The story is an attempt to explain an abstract concept (the problem of evil) insofar as it ultimately says that it is a mystery and that God, as God, cannot be fully understood by the mind of man (that’s what most of the dialogue in the book is about). It uses the literary technique of anthropopathism to do so. Satan gained control because human beings chose Him over God when it was time to make a choice between the two. And we choose his “way” every time we choose to sin. If we hadn’t done that, it would be a non-issue. But when we made that choice, God allowed it to occur. And that’s why he allowed Satan to torment Job.

It was not Job’s personal choice or failures that led to his torment – quite the opposite, we are told that Job is a good and godly man, who praises and gives thanks for his blessings – but simply God listening to Satan’s argument and seeking to prove the Accuser wrong.

Exactly: even the righteous suffer because of man’s cosmic rebellion and what it has brought about. This is what Christians agonize about, and what apologists have to try to explain. Atheists have to agonize over how to define good in a non-arbitrary, non-relativistic, objective way. And atheism has produced far worse fruits in the real world.

HaShem’s response at the end of Job is, in all of this, a bit amusing, since it’s an appeal to mystery. God has some grander plan than mortal minds can consider, so asking the question of “Why do bad things happen to good people?” is inane, at best. The Lord works in mysterious ways, so Job tells us.

He’s exactly right. We can understand a lot, with the help of revelation, but we can never fully understand a Being so far above us as God is.

1st Kings 22, likewise, makes reference to a deceiving spirit approaching God, who has asked the celestial choir who shall act to lure Ahab into destruction. Angel or demon, it’s clear that this spiritual principality acts only with the direct assent and direction of God.

Most people think this is an instance of the personification of the spirit of prophecy. It’s definitely not an evil spirit, though. Keil and Delitzsch Biblical Commentary on the Old Testament states concerning this:

The vision described by Micah was not merely a subjective drapery introduced by the prophet, but a simple communication of the real inward vision by which the fact had been revealed to him, that the prophecy of those 400 prophets was inspired by a lying spirit. The spirit (הרוּח) which inspired these prophets as a lying spirit is neither Satan, nor any evil spirit whatever, but, as the definite article and the whole of the context show, the personified spirit of prophecy, which is only so far a πνεῦμα ἀκάθαρτον τῆς πλάνης (Zechariah 13:2; 1 John 4:6) and under the influence of Satan as it works as שׁקר רוּח in accordance with the will of God. For even the predictions of the false prophets, as we may see from the passage before us, and also from Zechariah 13:2 and the scriptural teaching in other passages concerning the spiritual principle of evil, were not mere inventions of human reason and fancy; but the false prophets as well as the true were governed by a supernatural spiritual principle, and, according to divine appointment, were under the influence of the evil spirit in the service of falsehood, just as the true prophets were moved by the Holy Spirit in the service of the Lord. The manner in which the supernatural influence of the lying spirit upon the false prophets is brought out in Micah’s vision is, that the spirit of prophecy (רוח הנבואה) offers itself to deceive Ahab as שׁקר רוּח in the false prophets. Jehovah sends this spirit, inasmuch as the deception of Ahab has been inflicted upon him as a judgment of God for his unbelief. But there is no statement here to the effect that this lying spirit proceeded from Satan, because the object of the prophet was simply to bring out the working of God in the deception practised upon Ahab by his prophets. . . .

Jehovah has ordained that Ahab, being led astray by a prediction of his prophets inspired by the spirit of lies, shall enter upon the war, that he may find therein the punishment of his ungodliness. As he would not listen to the word of the Lord in the mouth of His true servants, God had given him up (παρέδωκεν, Romans 1:24, Romans 1:26, Romans 1:28) in his unbelief to the working of the spirits of lying. But that this did not destroy the freedom of the human will is evident from the expression תּפתּה, “thou canst persuade him,” and still more clearly from תּוּכל גּם, “thou wilt also be able,” since they both presuppose the possibility of resistance to temptation on the part of man.

This supports what I was just saying about how God could have put thoughts into the mind of Hitler or Rommel, etc., to influence the outcome of World War II. God likes to work in concert with us and our prayers (free will again). Lots of Christians were praying for an Allied victory in World War II, just as lots of Christians prayed and engaged in activism and voting that ended British and American slavery. God didn’t simply send brimstone and fire from heaven, because that’s not usually how He works.

Not that the Allies were perfect, either, in World War II. When we sought to end the Pacific War, it was by intrinsically evil acts: two nuclear bombs on civilian populations.

And while there are references later on to the power to cast out unclean spirits – the pneuma akathartoi – these are curious beasts. There is no infernal hierarchy, no mention of infernal powers. The Talmud actually describes shedim as a different class of being entirely; mortal, despite their generally non-corporeal forms, and in need of sustenance.

No particular comment on that . . .

You can take, from all of this, a very different interpretation, where Satan is not some fallen angel but, rather, exactly what the name HaSatan implies; the Accuser, a loyal servant whose duty it is to test humanity on behalf of God, with the unclean spirits commanded and exorcised merely a choir of the otherwise mundane and earthly ephemeral entities, who obey divine commandments but are antithetical to human life.

I don’t see that the Bible (especially the New Testament) teaches that.

But let’s set that interesting demonology aside for a moment and focus on a core question: If God has demonstrated a power to prevent demonic incursion into our world, but also a willingness to allow it anyway, the natural answer is that God is allowing it for some purpose. As Job demonstrates, we may be unclear or ignorant of such purposes, but God still chooses to allow it. To that end, God was responsible for all the suffering Job experienced.

Allowing is not total responsibility. That’s the equation that you have not established is the case. And just because God is omniscient and omnipotent doesn’t change that fact.

That’s really the core of it. If you take the Book of Job as a literal telling of events, Job’s suffering only happened because of God. Ergo, God is directly responsible.

The Satan portion is likely anthropopathic (i.e., not literal; a literary technique). But the theology fits fine with Christianity (and Judaism). But it didn’t “only happen because of God.” God allowed it to happen, just like he has allowed the devil to run free till the time of judgment comes.

If you then believe that Satan only has any such power because of God, you must likewise hold God responsible for all actions by infernal whim.

That doesn’t follow at all. I don’t how many times and how many different ways I have to say it. Just because God could change just about any particular in the universe (that isn’t contradictory or evil) doesn’t mean that He is responsible for every particular decision made by all creatures. Freedom is what it is and so is free will.

Libertarian free will

You’ll have to forgive me but I don’t find “it’s a mystery!” to be satisfying. If you can’t produce a reason to hold a specific set of beliefs, I can’t dissuade you, but you’re also going to have a hard time convincing me.

Well, quite obviously I ain’t just doing that, because if I was, this paper would be much shorter than it is! I am explaining as far as the human intellect can take this. Every Christian admits there is mystery, too, to things that are of God. That’s not unusual at all for any thinker (lest you think so). It’s not “blind faith.” So, for example, in science, there continue to be great mysteries. The big thing right now is dark matter and dark energy. Scientists believe in both, but know very little about them. They manage to believe without total, complete, comprehensive knowledge. They know enough to believe in them. And that’s how Christianity is.

I do not believe predestination is required to obliterate free will; I think the very concept of free will is paradoxical in and of itself. I laid out my reasoning in more complex terms last time but it can simply be focused on the question of “Why did someone make a decision?”

All decisions are the result of causal chains. There is a cause and an effect. If someone could theoretically have produced a different outcome from the same causes, the effect is random, because there is no relation between the causes and the effects.

Omniscience doesn’t enter into the question here; libertarian free will is a paradox from its inception. Omniscience just adjusts the level of moral responsibility that lies on God’s hands since, knowing the outcome from the start, they could change it to be different. Applying blame for actors that God essentially placed into that situation is blaming the victim.

Furthermore, even if something like libertarian free will did exist, you’ve demonstrated that the “outcome” of it – of sin – is unnecessary. You say that, unhampered by flesh, strife, Original Sin, or infernal influences, humanity would be sinless and pure, even with free will. Knowing that, absent those things, humanity would be perfectly good, God created them anyway, instead of simply creating humanity already in those perfect conditions. Or, likewise, God could have created humanity sufficiently capable of resisting all temptation and with the moral drive to do so, whereupon we would never sin, despite these issues.

He can’t do that and allow free will (i.e., a free will that would always make the right choice and avoid the whole evil detour). It’s possible, however, that there are worlds with unfallen creatures. C. S. Lewis wrote about that. But if they exist, it’s by the creatures’ choices, not because God wouldn’t allow them to do otherwise. The outcome is driven by the creature, not God. God gives them everything they need to make the right choice.

It’s simply inescapable. If God knew suffering would occur because of certain factors and could’ve avoided them, God is responsible for that suffering. You can argue it serves some greater purpose – and perhaps it might – but then the question arises of whether God could’ve achieved the same ends with a different means. Omnipotence demands we say yes.

I will add that a less perfect deity could be forgiven for these failings. A god who is not all-knowing may simply not know the outcome of their actions and just be doing their best. A god who is not all-powerful might simply not be able to bring about a perfect outcome. But for any deity that is ascribed perfection, it’s not really possible to escape these issues.

Philosopher Alvin Plantinga (whom many think is the greatest living Christian philosopher) doesn’t think so. See my paper, “Logical” Problem of Evil: Alvin Plantinga’s Decisive Refutation (The Problem of Evil is NOT a Disproof of God’s Existence, Goodness, or Omnipotence).

Good in a godless world

I have to start by saying that I do not believe rewards or later goodness “makes up” for suffering. I believe that, in the balance, it can be worth it to suffer for a worthy goal, but the better thing is to attain the goal without suffering. If you made your offer of blood in exchange for a vacation, I’d say that the benefit outweighs the suffering, but it’d be even better to get the benefit without the pain.

I make the same moral consideration with, say, giving a child a vaccine. It’s unpleasant for them, but it’s better they suffer a small pain and be tired for a few days than risk catching measles. However, if I can vaccinate a child without causing them any pain, I would. Why wouldn’t I? The suffering doesn’t add anything to the equation.

In the end, suffering isn’t erased by later rewards; the suffering is real, no matter what. Just like I don’t believe that apologies or later good deeds can “make up” for past misdeeds. They can demonstrate you’ve changed, they can show true contrition, and even just be a sign of being a good person, but you can’t “buy” your way into being a good person. There is no tally sheet that we all get to work off. Done, as they say, is done.

We would say that human beings don’t have exhaustive knowledge about what the higher purpose for suffering may be. I was just watching the Ken Burns documentary on Lewis and Clark, and in the features they interviewed him and asked about his mother dying when he was twelve. And he noted that the greatest thing his mother ever did for him was die when he was young. It sounded shocking at first. But he didn’t mean that he wished her to die; rather, the point was that her death forced him to confront “real life” and his own goals and aspirations, and he thinks that it literally made him what he is: the world’s greatest documentary filmmaker. It doesn’t make suffering less painful, but good things can come from it.

If there’s something I still enjoy and appreciate about Christianity, it’s the idea of grace and redemption; it’s something I still hold onto as a belief. Not in the form of a divinely granted salvific power, but simply that people can grow and change, and that letting go and forgiving past transgressions is important to our health moving forwards. We can’t change the past, but we can move on and move forwards; sins washed away by our transformation into a better person.

No one can do any good thing without God’s grace, and it must be asked for and “worked with” (including repentance for sins). You can hardly ask for something from a being, if He doesn’t exist. But the principle makes sense, in a world with God. Without God, it makes little sense. It’ll work to an extent, because that’s how God designed it, but if there had never been a God, the world would be far, far worse than it is. And the atheist is always free to redefine any sin away. He or she is his own king and master. No one to be accountable to in the final analysis.

Now… On the meat of the topic of goodness in a godless world… Yes, I do believe people are basically good. There’s a wonderful parable by the Confucian scholar Mencius, called the Allegory of the Well, which I think illustrates it nicely.

If a human being – high or low, rich or poor, virtuous or venal – is walking down a road and sees a child playing by a well, and that child trips and falls, their innate reaction will be to reach for that child to save them. That most basic, unthinking, unfeeling instinct in all humans is to help and protect one another. Humans, like raindrops in a forest, will always flow towards the common river. Like water being forced uphill, people can be made to act against this instinct, but that core instinct – that care for one another – lies in the heart of everyone.

And we say it is because God already put that good and decent impulse in them. Where we agree is to say that if a person rejects this understanding of charity and compassion, it’s their own fault.

It’s a pleasant and simplistic allegory – as allegories are – and humanity is complex and complicated, with some people born with defects in empathy, say, but I think its essential truth is correct: Humans, at their basest level, want to do good for one another. It takes other circumstances to make that no longer the case.

They do before they are corrupted by sin. This is why children before the age of reason seem so “innocent.” They actually literally are more innocent than those who know more and thus sin more.

It’s why, in every part of the world where there has been an atrocity, those in charge have taken special pains to ensure that those doing the actual deed are as mentally distanced from the victims as possible. Even those people who committed history’s worst atrocities, even the Nazis, engaged in this behaviour, to hide from themselves what they were doing. Prior to the use of gas chambers, soldiers who were made to shoot Germany’s “undesirables” frequently took their own lives, because the horror of what they’d done stained itself indelibly into their souls.

Yes, because somewhere buried down deep, remains the conscience that comes from God.

So, as I said, I do have reasons for believing people are basically good. Evil exists within us too, but I think we are, overall, good. Weak, perhaps, but good. But I also said that this is an article of faith for me. I don’t really have absolute proof either way. You can ascribe that to the fumes of faith if you will, but it’s not something I can really reason perfectly for or against.

I believe people to be basically good, in absence of perfect evidence one way or the other. In this, I am not, as you say, hyper-rational.

If we’re “basically good” on the whole, then all the human-caused suffering we see is the remarkable thing to explain. The world shouldn’t and wouldn’t be what it is, and this is your “problem of good.” The good things would be far more prevalent than the bad, if this were true. You have a lot more to explain than I do, because I believe in original sin and actual sin and human beings with free will who rebel against the All-Good God Who made them.

But in the balance, assume I’m wrong. Assume that there are no gods, no Heaven or Hell, that things are as bleak as you say, and that humanity is fundamentally malicious at its core.

It wouldn’t affect one iota as to whether atheism is true or not. Truth doesn’t care about our feelings; it simply is. If God exists, it doesn’t matter whether I find their actions immoral or not; they do exist. Likewise, if God does not exist, it doesn’t matter how bleak or uncomfortable or despairing it makes you feel; they simply don’t. Our wants or desires are not the moral arbiter of a belief’s correctness or falsity.

But what is the moral arbiter? This is your difficulty. All you have done is tell me what isn’t the moral arbiter. And I don’t blame you, because in atheism there is nothing beyond human beings. If we determine right and wrong, then given world history and the long sad record of men doing evil to one another, to me that is an exponentially more difficult problem than the problem of evil in the theistic worldview. And it’s why — I submit — you have written very little about it. Atheists have no solid answer to it, from where I sit.

And as a conclusion on why I care… I don’t believe God exists, but you definitely do. I share this world with people of all religious faiths, and I find their ideas and perspectives fascinating. It’s interesting to engage with people and discuss their perspectives; to test their ideas and my own, and see what shakes out. Because even if I don’t believe in your deity, you do, and it clearly shapes and affects your beliefs on things like morality and responsibility, which are at the core of this discussion.

I deeply appreciate your cordiality and “normal” behavior. Christians are confronted constantly with atheists who seem to get a charge out of mocking and belittling us and telling whoppers about how anti-intellectual, anti-scientific, and childishly gullible we are. I can’t tell you how refreshing it is to simply have a good discussion, minus all the insults and straw men. Rest assured also that my criticisms I have are of your views, not you as a person. You seem like a really cool, likable person.

Sorry for taking so long… But hopefully this was worth the wait.

It certainly was. No need for apologies. Thanks!

***

Photo credit: Cover of the 1888 edition of Goody Two-Shoes, published by McLoughlin Bro’s. of New York, US. The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes was a children’s story published by John Newbery in London in 1765. [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

Summary: More great dialogue with a friendly, non-insulting agnostic on the problem of evil: that thorniest of issues; along with my retort regarding the corresponding atheist “problem of good.”