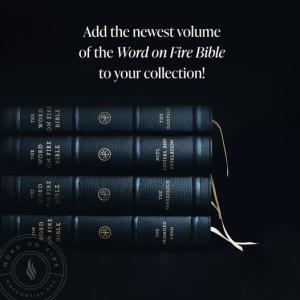

I have reviewed the previous three installments of Bishop Robert Barron’s planned seven-volume Word on Fire Bible: Volume I: The Gospels, Volume II: Acts, Letters and Revelation, and Volume III: The Pentateuch. Volume IV: The Promised Land is, like all of the others, bound in beautiful leather, with page edges of brilliant gold foil. The text utilizes the NRSV version, and is chock-full of relentlessly insightful and interesting commentary from Catholic luminaries, as well as gorgeous reproductions of great Catholic art. Word on Fire provides the following general introduction:

Volume IV of The Word on Fire Bible features the books of Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1 and 2 Samuel, and 1 and 2 Kings . . . [with] over 75 commentaries from Bishop Robert Barron and over 175 commentaries from mystics, artists, and scholars throughout history. This volume also includes 40 works of art with commentary, 8 word studies of the original Hebrew, and introductions written by Peter Kreeft, Sally Read, Katie Prejean McGrady, Richard DeClue, and more.

I was particularly interested in the commentary offered regarding the book of Joshua and the so-called “conquest of Canaan,” having devoted 26 pages to that topic in my recent book, The Word Set in Stone: How Archaeology, Science, and History Back Up the Bible (Catholic Answers Press: 2023). Bishop Barron wrote about this in his commentary, “The Warfare of the Ban” on page 66:

We should address with focus and care this issue that bedevils many commentators today and gives fuel to the enemies of religion: How could the God who presides over the bloody conquest of the Promised Land be anything other than a moral monster? The “new” atheists of the early twenty-first century — Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris, and especially Richard Dawkins — obsessively turned to these and other similar texts to show what they took to be the moral ambiguity of the portrait of God in the Bible.

Bishop Barron then summarized three “classic attempts to solve this problem”: the first was St. Irenaeus’ emphasis on the developmental or progressive nature of revelation in which God’s nature and actions are more understood over time (Joshua’s time being a relatively primitive era). The second explanation, taken by St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas and many others (my own favored interpretation), sees the conquest as “a delegated exercise of the divine justice” (p. 67). I described this in my book, as follows:

A point can be reached at which certain segments of the human population are beyond all hope of redemption, and so God judges them, up to and including sentencing them to death. He usually uses human agents to do so—in this instance, Joshua’s army. (p. 226)

I also noted that God wasn’t exercising double standards (i.e., protecting His “chosen” people and harshly judging others), since He also predicted through His prophets the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple, if the Israelites were disobedient and unfaithful. This happened twice: in the sixth century BC and first century AD, with many thousands of deaths and/or subsequent enslavement.

Bishop Barron’s third interpretation (his own preferred one), derived from the Church father, Origen, who

argues that the whole of the Bible should be read from the standpoint of an event narrated in the last book of the Bible — namely, the appearance of the Lamb standing as though slain. . . . Therefore, any interpretation of any section of the Bible that leads to the conviction that God is an avenging, violent tyrant is, ipso facto, incorrect. (pp. 68-69)

What I discovered in approaching the book and the events in it from an archaeological perspective, is that Joshua’s “conquest’ was not, in fact, nearly as bloody and “cruel” as is usually assumed. Archaeologist Kenneth A. Kitchen, for example, observes: “The text of Joshua does not imply huge and massive fiery destructions of every site visited (only Jericho, Ai, and Hazor were burned)” (On the Reliability of the Old Testament [Grand Rapids and Cambridge: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003], 183). Archaeologist James K. Hoffmeier concurs:

A close look at the terms dealing with warfare in Joshua 10 reveals that they do not support the interpretation that the land of Canaan and its principal cities were demolished and devastated by the Israelites. (Israel in Egypt: The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition [New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996], 34-35)

The historical record shows that there was a great deal of peaceful assimilation and coexistence alongside the earlier Canaanite inhabitants, for a long time prior to the Israelite monarchy. As an analogy, the early history of England — involving Celts, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, and Normans — is also increasingly believed to have been largely of this nature. People didn’t fight so much as they intermarried and culturally influenced each other. In other words, bolstered by this analysis, I deny much of the widely accepted premise regarding Joshua’s allegedly “bloodthirsty” and “cruel” entrance into Canaan: a scenario emphasized by those hostile to Christianity, God, and the Bible.

The great King David figures prominently in this volume. St. Augustine is cited regarding his terrible sin of deliberately causing a man to be killed in battle, so he could have his wife, Bathsheba:

he cried out after hearing God’s fearsome threats, and said, “I have sinned”; and shortly afterward heard, “The LORD has put away your sin.” . . . in these three syllables the flames of the heart’s sacrifice rose up to heaven. So those who have done genuine penance, and have been absolved . . . (p. 421)

Magnificent commentaries on King David abound: too many to even select another in this relatively short review; so I will merely make this statement of praise for the storehouse of treasures herein and move on.

David’s son, King Solomon was known for being exceedingly wise (see 1 Kings 3:9). An excerpt from a General Audience of Pope Francis provides an elegantly simple definition of wisdom: “Wisdom is precisely this: it is the grace of being able to see everything with the eyes of God. It is simply this: it is to see the world, to see situations, circumstances, problems, everything through God’s eyes. This is wisdom” (p. 501). But, sadly, Solomon — like King Saul — fell into serious sin later in life, and he may not have ever repented of it, as David did. His downfall is a metaphor for the perpetual human condition of sin and rebellion. Andrew Tolkmith explains, in the section, “Solomon Worshiping Idols”:

Solomon, influenced by his many foreign wives, built high places for Chemosh, the god of the Moabites, and Molech, the god of the Ammonites [1 Kings ch. 11] . . .

Solomon . . . who successfully built the defining monument of the Jewish religion, to whom God promised a throne forever, nevertheless allows his heart to be turned away from the Lord. Solomon’s idolatry is all the more shocking in light of his father David’s reputation as a man after God’s own heart (1 Sam. 13:14). . . .

The actions of Solomon, whose reign is arguably the high point of Israel’s entire history, nevertheless set in motion a process that will eventually culminate in Israel’s demise and the Babylonian exile. (p. 541)

Bishop Barron follows up on these thoughts: “What is perhaps most striking, and most unnerving, about 2 Kings is the way it ends . . . [with] the utter demolition of Solomon’s kingdom and the destruction of his temple” (p. 692).

A happier story is that of Samson, another man of great faults and sins, just as in the cases of David and Solomon. But his famous end (bringing an entire house down on his enemies) was like David’s and not Solomon’s. Bishop Barron comments on him:

Perhaps the most important theological point to understand is that whatever strength we have comes ultimately from God and is enhanced by our devotion to God . . . Samson — betrayed, corralled by his enemies, tortured, and mocked — is an anticipation of Christ in his Passion. (p. 192)

Incidentally, in one of my articles, I offer archaeological confirmation that there were indeed Philistine buildings during Samson’s time (the first half of the 11th century B.C.) that were wholly or mostly supported by two pillars, which could be reached by a large man with a long arm span. The Bible was historically accurate in this story, as always!

As King David and Samson foreshadowed Christ in some ways, so Ruth foreshadowed in part the Blessed Virgin Mary and was an ancestor of our Lord Jesus Christ. Scripture is filled with such foreshadowings or prototypes or “types and shadows” as they are sometimes called. Former atheist Sally Read, in her “Introduction to Ruth,” offers some illuminating insights:

This scene, where Ruth earlier marvels that she has “found favor,” [Ruth 2:10, 12] put me in mind also of the Annunciation, when, centuries later, the angel Gabriel comes to the Virgin Mary and uses these words of Ruth as he tells her that she will bear the Son of God. Both Ruth and Mary consent to a path that potentially holds little but shadows and risk. By their consent, both women, in different ways, set in motion the salvation of the world. . . .

Her actions, though small and seemingly limited to her own story, ensure the genealogy of the Son of God. We can’t know the effect our lives will have on those around us and those after us. (pp. 213-214)

Buy this Bible and this entire set! It’s wonderful and inspiring, will edify and educate you in equal measure, and make you appreciate all the more the amazing revelation that God gave to us: His infallible Sacred Scripture.

***

Photo Credit: photograph taken from advertising material posted on the Word on Fire website and on Facebook.

Summary: My book review and recommendation of The Word on Fire Bible: Volume IV: The Promised Land, highlighting commentary on Joshua, David, Solomon, Samson, & Ruth.