Rev. Dr. Jordan B. Cooper is a Lutheran pastor, adjunct professor of Systematic Theology, Executive Director of the popular Just & Sinner YouTube channel, and the President of the American Lutheran Theological Seminary (which holds to a doctrinally traditional Lutheranism, similar to the Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod). He has authored several books, as well as theological articles in a variety of publications. All my Bible citations are from RSV, unless otherwise indicated. Jordan’s words will be in blue.

This is my 17th reply to Jordan (many more to come, because I want to interact with the best, most informed Protestant opponents). All of these respectful critiques can be found in the “Replies to Jordan Cooper” section at the top of my Lutheranism web page. Thus far, he has chosen not to respond to any of my critiques. He informed me of the reasons why on my Facebook page, on 17 April 2024:

I appreciate your thoughtful engagement with my material. I also appreciate not being called “anti-Catholic,” as I am not. Unfortunately, it is just a matter of time that I am unable to interact with the many lengthy pieces you have put together. With teaching, writing, running a publishing house, podcasting, working at a seminary, and doing campus ministry, I have to prioritize, which often means not doing things that would be very much worthwhile simply for lack of time.

I appreciate the explanation and nevertheless sincerely hope that Dr. Cooper does have more time and desire to dialogue with me in the future. I think we could have some good and constructive — and civil – discussions. In the meantime, I will continue to write what he regards as “thoughtful” and “worthwhile” responses.

***

I am replying to Jordan Cooper’s video, “Sola Scriptura and the Canon” (6-10-24).

Someone else introduces the topic (his words in green):

Likewise the order of the writings of the New and Eternal Testament, which only the holy and Catholic Church supports. Of the Gospels, according to Matthew one book, according to Mark one book, according to Luke one book, according to John one book.

The Epistles of Paul the Apostle in number fourteen. To the Romans one, to the Corinthians two, to the Ephesians one, to the Thessalonians two, to the Galatians one, to the Philippians one, to the Colossians one, to Timothy two, to Titus one, to Philemon one, to the Hebrews one.

Likewise the Apocalypse of John, one book. And the Acts of the Apostles one book. Likewise the canonical epistles in number seven. Of Peter the Apostle two epistles, of James the Apostle one epistle, of John the Apostle one epistle, of another John, the presbyter, two epistles, of Jude the Zealut, the Apostle one epistle.

The plain fact of the matter is that the canon of the Bible was not settled in the first years of the Church. It was settled only after repeated (and perhaps heated) discussions, and the final listing was determined by the pope and Catholic bishops. This is an inescapable fact, no matter how many people wish to escape from it.

That’s true, too; however, it was merely reiterating at a higher authority level what had already been decreed exactly 1164 years earlier (382 to 1546). That’s not just me (the beloved Catholic apologist) asserting that. It’s the following reputable Protestant source:

A council probably held at Rome in 382 under St. Damasus gave a complete list of the canonical books of both the Old Testament (also known as the ‘Gelasian Decree’ because it was reproduced by Gelasius in 495), which is identical with the list given at Trent. (The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 2nd edition, edited by F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, Oxford University Press, 1983, 232)

In terms of the Old Testament, the Council of Rome in 382 included Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Tobit, Judith, and 1 and 2 Maccabees. Baruch was included as part of Jeremiah, as in St. Athanasius’ list of 15 years previously. This is indeed identical with the Tridentine list, and comprises the seven “extra” deuterocanonical books in Catholic Bibles which Protestants reject from the canon as “apocryphal.” Nevertheless, there they are in the Council of 382. The Council of Carthage accepted the same list, as detailed by the great Protestant scholar Brooke Foss Westcott (A General Survey of the History of the Canon of the New Testament, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1980, rep. from 6th ed. of 1889, 440). Renowned Protestant Church historian Philip Schaff also concurs:

This canon [of Carthage] remained undisturbed till the sixteenth century, and was sanctioned by the council of Trent at its fourth session. (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, vol. 3: Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1974 [orig. 1910], 609-610)

***

“Please Hit ‘Subscribe’”! If you have received benefit from this or any of my other 4,800+ articles, please follow this blog by signing up (with your email address) on the sidebar to the right (you may have to scroll down a bit), above where there is an icon bar, “Sign Me Up!”: to receive notice when I post a new blog article. This is the equivalent of subscribing to a YouTube channel. Please also consider following me on Twitter / X and purchasing one or more of my 55 books. All of this helps me get more exposure, and (however little!) more income for my full-time apologetics work. Thanks so much and happy reading!

***

Apostolic Fathers 90-160 AD*Gospels Generally accepted by 130Justin Martyr’s “Gospels” contain apocryphal material

Acts Scarcely known or quoted

Pauline Corpus Generally accepted by 130, yet quotations are rarely introduced as scriptural

Philippians, 1 Timothy: x Justin Martyr

2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon: x Polycarp, Justin Martyr

Hebrews Not considered canonical

? Clement of Rome

x Polycarp, Justin Martyr

James Not considered canonical; not even quoted

x Polycarp, Justin Martyr

1 Peter Not considered canonical

2 Peter Not considered canonical, nor cited

1, 2, 3 John Not considered canonical

x Justin Martyr

1 John ? Polycarp / 3 John x Polycarp

Jude Not considered canonical

x Polycarp, Justin Martyr

Revelation Not canonical

x Polycarp

Irenaeus to Origen (160-250)

Gospels Accepted

Acts Gradually accepted

Pauline Corpus Accepted with some exceptions:

2 Timothy: x Clement of Alexandria

Philemon: x Irenaeus, Origen, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria

Hebrews Not canonical before the 4th century in the West.

? Origen

* First accepted by Clement of Alexandria

James Not canonical

? First mentioned by Origen

x Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria

1 Peter Gradual acceptance

* First accepted by Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria

2 Peter Not canonical

? First mentioned by Origen

x Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria

1 John Gradual acceptance

* First accepted by Irenaeus

x Origen

2 John Not canonical

? Origen

x Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria

3 John Not canonical

? Origen

x Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria

Jude Gradual acceptance

* Clement of Alexandria

x Origen

Revelation Gradual acceptance

* First accepted by Clement of Alexandria

x Barococcio Canon, c.206

Epistle of Barnabas * Clement of Alexandria, Origen

Shepherd of Hermas * Irenaeus, Tertullian, Origen, Clement of Alexandria

The Didache * Clement of Alexandria, Origen

The Apocalypse of Peter * Clement of Alexandria

The Acts of Paul * Origen

* Appears in Greek, Latin (5), Syriac, Armenian, & Arabic translations

Gospel of Hebrews * Clement of AlexandriaOrigen to Nicaea (250-325)

Gospels, Acts, Pauline Corpus Accepted

Hebrews * Accepted in the East

x, ? Still disputed in the West

James x, ? Still disputed in the East

x Not accepted in the West

1 Peter Fairly well accepted

2 Peter Still disputed

1 John Fairly well accepted

2, 3 John, Jude Still disputed

Revelation Disputed, especially in the East

x DionysiusCouncil of Nicaea (325)

Questions canonicity of James, 2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, and Jude

From 325 to the Council of Carthage (397)

Gospels, Acts, Pauline Corpus, 1 Peter, 1 John accepted

Hebrews Eventually accepted in the West

James Slow acceptance

Not even quoted in the West until around 350!

2 Peter Eventually accepted

2, 3 John, Jude Eventually accepted

Revelation Eventually accepted

x Cyril of Jerusalem, John Chrysostom, Gregory Nazianz

Epistle of Barnabas * Codex Sinaiticus – late 4th century

Shepherd of Hermas * Codex Sinaiticus – late 4th centurySources for New Testament Canon Chart (all Protestant):

1) J. D. Douglas, editor, New Bible Dictionary, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1962 edition, 194-198.

2) F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone, editors, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2nd edition, 1983, 232, 300, 309-10, 626, 641, 724, 1049, 1069.

3) Norman L. Geisler & William E. Nix, From God to Us: How We Got Our Bible, Chicago: Moody Press, 1974, 109-12, 117-125.

That’s quite a bit of uncertainty, if you ask me. The Church clearly needed an authoritative pronouncement, seeing that no single person came up with the complete New Testament until 367 AD. That’s what — in effect — sola Scriptura (which no one believed in, in the first place) produced.

3:37-3:53 what’s happening is the Church: they’re not putting together the canon but the Church is recognizing what God has inspired and really this is just the nature of understanding that scripture is inspired is because we have faith that scripture is inspired . . .

No one disagrees with that (the Catholic Church declared the parameters of the canon; it did not create it; nor was it claiming to be “over” it), but it doesn’t solve the problem at hand (which books were canon) as long as equally honest and pious folks were disagreeing on the biblical canon. It obviously had to be resolved somehow. Its one thing to proclaim these platitudes about biblical inspiration. The actual “messy” complicated history — the concrete facts — (as I have shown) shows a lot of disagreement alongside the significant agreement.

3:53-3:59 We also have faith that God would guide his people to know what the books that he has inspired.

It’s not always so simple to determine which book was actually part of the Bible, See:

*

Practical Matters: Perhaps some of my 4,800+ free online articles (the most comprehensive “one-stop” Catholic apologetics site) or fifty-five books have helped you (by God’s grace) to decide to become Catholic or to return to the Church, or better understand some doctrines and why we believe them.

Or you may believe my work is worthy to support for the purpose of apologetics and evangelism in general. If so, please seriously consider a much-needed financial contribution. I’m always in need of more funds: especially monthly support. “The laborer is worthy of his wages” (1 Tim 5:18, NKJV). 1 December 2021 was my 20th anniversary as a full-time Catholic apologist, and February 2022 marked the 25th anniversary of my blog.

PayPal donations are the easiest: just send to my email address: apologistdave@gmail.com. Here’s also a second page to get to PayPal. You’ll see the term “Catholic Used Book Service”, which is my old side-business. To learn about the different methods of contributing (including Zelle), see my page: About Catholic Apologist Dave Armstrong / Donation Information. Thanks a million from the bottom of my heart!

*

***

*

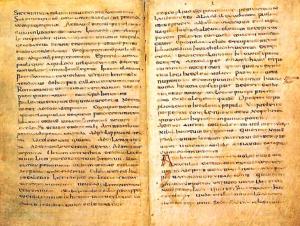

Photo credit: Muratorian Fragment (biblical manuscript). Bibliotheca Ambrosiana, Cod. J 101 sup. [source] [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

Summary: Lutheran apologist Jordan Cooper argues that the NT biblical canon arose spontaneously in history by sola Scriptura. I show how binding conciliar Church authority was required.