Amazing Astronomically Verified Data in Relation to the Journey of the Wise Men & Jesus’ Birth & Infancy

Matthew 2:1-12 (RSV) Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, behold, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem, saying, [2] “Where is he who has been born king of the Jews? For we have seen his star in the East, and have come to worship him.” [3] When Herod the king heard this, he was troubled, and all Jerusalem with him; [4] and assembling all the chief priests and scribes of the people, he inquired of them where the Christ was to be born. [5] They told him, “In Bethlehem of Judea; for so it is written by the prophet: [6] `And you, O Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; for from you shall come a ruler who will govern my people Israel.'” [7] Then Herod summoned the wise men secretly and ascertained from them what time the star appeared; [8] and he sent them to Bethlehem, saying, “Go and search diligently for the child, and when you have found him bring me word, that I too may come and worship him.” [9] When they had heard the king they went their way; and lo, the star which they had seen in the East went before them, till it came to rest over the place where the child was. [10] When they saw the star, they rejoiced exceedingly with great joy; [11] and going into the house they saw the child with Mary his mother, and they fell down and worshiped him. Then, opening their treasures, they offered him gifts, gold and frankincense and myrrh. [12] And being warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they departed to their own country by another way.

Joel 2:30 And I will give portents in the heavens . . .

I. Who Were the “Wise Men” or “Magi”? / Their Journey to Israel

The Magi were originally a Median (northwest Persian) tribe (Herodotus [Hist.] i.101). They performed priestly functions (Xen. Cyrop. viii), perhaps due to Zoroaster (Zarathustra) possibly having belonged to the tribe (or belief that he did), and studied astronomy and astrology: in part learned from Babylon [1]. Daniel (1:20; 2:27; 5:15) uses the word to describe “wise men” / “astrologers who interpret dreams and messages” [5].

Clement of Alexandria, Diodorus of Tarsus, Chrysostom, Cyril of Alexandria, . . . and others are probably right in bringing them from Persia. Sargon’s settlement of Israelites in Media (circa 730-728 BC (2 Kings 17:6)) accounts for the large Hebrew element of thought . . . Median astronomers would thus know Balaam’s prophecy of the star out of Jacob (Numbers 24:17). That the Jews expected a star as a sign of the birth of the Messiah is clear from the tractate Zohar of the Gemara and also from the title “Son of the Star” (Bar Kokhebha) given to a pseudo-Messiah. [1] The sudden appearance of a new and brilliant star suggested to the Magi the birth of an important person. They came to adore him — i.e., to acknowledge the Divinity of this newborn King (vv. 2, 8, 11). . . .

It is likely, however, that the Magi were familiar with the great Messianic prophesies. Many Jews did not return from exile with Nehemias. When Christ was born, there was undoubtedly a Hebrew population in Babylon, and probably one in Persia. At any rate, the Hebrew tradition survived in Persia. . . . We may readily admit that the Magi were led by such hebraistic and gentile influences to look forward to a Messias [Messiah] who should soon come. [2] [In] Yemen, . . . kings professed the Jewish faith from around 120 B.C. to the sixth century of our era. [4] To the head of this caste, Nergal Sharezar, Jeremias gives the title Rab-Mag, “Chief Magus” (Jeremiah 39:3, 39:13, in Hebrew original . . . [2]

No Church father regarded them as kings [2]. They were not magicians, but rather, “fundamentally” Zoroastrians: a religion that forbade sorcery [2]:

The Magi could have been Zoroastrians and careful watchers of the sky, certainly astrologers, in the ancient Babylonian and Assyrian sense, and not in the Hellenic sense. We note that in the original tradition of Mesopotamia the sky’s appearance was seen as a “reflex” and sometimes an “anticipation” of what happened on Earth, but without any implication of causality and astrolatry. [20]

The Bible doesn’t mention how many Magi there were. The number three is deduced from the three gifts they gave (gold, frankincense, and myrrh: Mt 2:11). Some fathers refer to three wise men [2].

East of Palestine, only ancient Media, Persia, Assyria, and Babylonia had a Magian priesthood at the time of the birth of Christ. From some such part of the Parthian Empire the Magi came. They probably crossed the Syrian Desert, lying between the Euphrates and Syria, reached either Haleb (Aleppo) or Tudmor (Palmyra), and journeyed on to Damascus and southward, by what is now the great Mecca route (darb elhaj, “the pilgrim’s way”), keeping the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan to their west till they crossed the ford near Jericho. We have no tradition of the precise land meant by “the east”. It is Babylon, according to St. Maximus (Homil. xviii in Epiphan.); and Theodotus of Ancyra (Homil. de Nativitate, I, x); Persia, according to Clement of Alexandria (Stromata I.15) and St. Cyril of Alexandria (In Is., xlix, 12); . . . [2]

They may have (but not necessarily) arrived either a little over a year after Jesus’ birth [2], or up to two years after:

Herod had found out from the Magi the time of the star’s appearance. Taking this for the time of the Child’s birth, he slew the male children of two years old and under in Bethlehem and its borders (v. 16). Some of the Fathers conclude from this ruthless slaughter that the Magi reached Jerusalem two years after the Nativity (St. Epiphanius, “Haer.”, LI, 9; Juvencus, “Hist. Evang.”, I, 259). . . . Only one early monument represents the Child in the crib while the Magi adore; in others Jesus rests upon Mary’s knees and is at times fairly well grown . . . [2]

My view is that the visit of the wise men occurred when Jesus was about a year old.

From Persia, whence the Magi are supposed to have come, to Jerusalem was a journey of between 1000 and 1200 miles. Such a distance may have taken any time between three and twelve months by camel. [2]

Camels “can easily carry an extra 200 pounds and can walk about 20 miles a day through the harsh desert climate” [3]. Using this figure and the high estimate of the distance above, it comes out to exactly sixty days for the journey. Presumably there were resting periods and side-journeys to towns to replenish supplies, etc., which might add another month, bringing it to three. “The Bible History Guy” opines:

The travel time from Babylon to Jerusalem was about four months. This allowed two months for the Magi to confer, decide the meaning of what they had seen, plan for their trip, possibly get political approval to pass from Parthian territory into enemy Roman territory, and gather their precious gifts for the Messiah – which may have involved some fundraising. [10]

Persia would have been about twice as far, but it depends on preparation time, how many stops and breaks, etc. There was a six-month “window” for the journey to line up with seeing the star both in Persia and in Israel when they arrived (more on that below). So this aspect lines up pretty well in the overall theory that shall be laid out as we proceed.

II. Star in the “East” or in the West?

What does it mean that the wise men saw the star “in the east” (Mt 2:2), but then traveled west to Bethlehem? John Mosley, program supervisor at the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles provides a perfectly reasonable explanation:

This has been interpreted to mean either that the star was in the eastern part of the sky or that the wise men were in the eastern part of the world when they saw it, but the actual situation is not so ambiguous. The Greek phrase, “en te anatole” simply means “as it rose” or “at its rising” which of course is always in the eastern sky, and does not refer to the location of the observer. Some authors interpret the phrase to mean that the magi observed the star’s predawn heliacal rising with the sun, . . . the New English Bible . . . [reads] “We observed the rising of His star…” and “the star which they had seen at its rising …” [7]

Other Bible versions are similar to the NEB. I’ve found fifteen:

NIV / ESV / Weymouth / Moffatt / Williams . . . we saw his star when it rose . . .

TEV (“Good News”): . . . we saw his star when it came up in the east . . .

NRSV . . . we observed his star at its rising . . .

REB . . . we observed the rising of His star . . .

Barclay / Goodspeed . . . we have seen his star rise . . .

Amplified . . . we have seen His star in the East at its rising . . .

Beck . . . we saw his star rise . . .

Jerusalem . . . we saw his star as it rose . . .

NAB / Wuest . . . we observed his star at its rising . . .

Starting in August, 3 BC, Jupiter rose in the east as a morning star and then came into conjunction with Venus. This started a series of six conjunctions in that year and the next: five with other planets and one with Regulus. At the end of 2 BC, Jupiter (always one of the brightest objects in the sky) appeared to be moving westward, towards Jerusalem from the east. [17]

III. When Did Herod the Great Die? (4 BC or Later)? / Jewish Historian Josephus’ Date

The “conventional wisdom” (e.g., Encyclopaedia Britannica) is that he died in 4 BC. This has a central bearing on the question of the year of Jesus’ birth (which is believed by all to be 1-2 years before Herod died, for the deductive reasons explained above). If we have a different year for Jesus’ birth, then we have to look at different astronomical data for when the star of Bethlehem appeared, and what it was, etc. Historians have primarily replied on the historian Josephus (37 – c. 100) for determination of this date, as influentially interpreted by Protestant theologian / historian Emil Schürer in his 1891 book, A History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus Christ. Physicist John A. Cramer noted that the lunar eclipse preceding Herod’s death, as noted by Josephus, may have been at a later date than the usually accepted one:

This date [4 BC] is based on Josephus’s remark in Antiquities 17.6.4 that there was a lunar eclipse shortly before Herod died. This is traditionally ascribed to the eclipse of March 13, 4 B.C. Unfortunately, this eclipse was visible only very late that night in Judea and was additionally a minor and only partial eclipse. There were no lunar eclipses visible in Judea thereafter until two occurred in the year 1 B.C. Of these two, the one on December 29, just two days before the change of eras, gets my vote since it was the one most likely to be seen and remembered. That then dates the death of Herod the Great into the first year of the current era, four years after the usual date. [6]

This argument was also advanced in the 19th century by scholars Édouard Caspari, Florian Riess, and others, so it’s not new. Josephus (Antiquities 17.9.3, The Jewish War 2.1.3) also noted that Herod died before the Jewish Passover holy day. These are our two historical clues. John A. Cramer continues his “which date based on a lunar eclipse is most plausible?” analysis:

I do not mean to claim I know the right answer. . . . The key information comes, of course, from Josephus who brackets the death by “a fast” and the Passover. He says that on the night of the fast there was a lunar eclipse—the only eclipse mentioned in the entire corpus of his work. Correlation of Josephus with the Talmud and Mishnah indicate the fast was probably Yom Kippur. Yom Kippur occurs on the tenth day of the seventh month (mid-September to mid-October) and Passover on the 15th day of the first month (March or April) of the religious calendar. Josephus does not indicate when within that time interval the death occurred. Only four lunar eclipses occurred in the likely time frame: September 15, 5 B.C., March 12–13, 4 B.C., January 10, 1 B.C. and December 29, 1 B.C.

The first eclipse fits Yom Kippur, almost too early, but possible. It was a total eclipse that became noticeable several hours after sundown, but it is widely regarded as too early to fit other information on the date. The favorite 4 B.C. eclipse seems too far from Yom Kippur and much too close to Passover. This was a partial eclipse that commenced after midnight. It hardly seems a candidate for being remembered and noted by Josephus. The 1 B.C. dates require either that the fast was not Yom Kippur or that the calendar was rejiggered for some reason.

The January 10 eclipse was total but commenced shortly before midnight on a winter night. Lastly, in the December 29 eclipse the moon rose at 53 percent eclipse and its most visible aspect was over by 6 p.m. It is the most likely of the four to have been noted and commented on. None of the four candidates fits perfectly to all the requirements. I like the earliest and the latest of them as the most likely. The most often preferred candidate, the 4 B.C. eclipse, is, in my view, far and away the least likely one. [6]

Noted professor of New Testament history and archaeology Jack Finegan (1908-2000) took a different approach, and examined the manuscript evidence in Josephus:

[T]the currently known text of Josephus’ Ant. 18.106 states that [Herod] Philip died in the twentieth year of Tiberius (A.D. 33/34 . . .) after ruling for thirty-seven years. This points to Philips’ ascension at the death of Herod in 4 B.C. (4 years B.C. + 33 years A.D. = 37 years) . . Florian Riess reported that the Franciscan monk Molkenbuhar claimed to have seen a 1517 Parisian copy of Josephus and an 1841 Venetian copy in each of which the text read “the twenty-second year of Tiberias.” The antiquity of this reading has now been abundantly confirmed.

In 1995 David W. Beyer reported to the Society for Biblical Literature his personal examination in the British Museum of forty-six editions of Josephus’ Antiquities published before 1700 among which twenty-seven texts, all but three published before 1544 read “twenty-second year of Tiberius,” while not one single edition published prior to 1544 read “twentieth year of Tiberius.”

Likewise, in the Library of Congress five more editions read the twenty-second year,” while none prior to 1544 records the “twentieth year.” It was also found that the oldest versions of the text give variant lengths of reign for Philip of 32 to 36 years. But if we still allow for a full thirty-seven year reign, then “the twenty-second year of Tiberius” (A.D. 35/36) points to 1 B.C. (1 year B.C. + 36 years A.D. = 37 B.C.) as the year of death of Herod. This is therefore the date which is accepted in the present book. Accordingly, if the birth of Jesus was two years or less before the death of Herod in 1 B.C., the date of birth was in 3 or 2 B.C., presumably precisely in the period 3/2 B.C., so consistently attested by the most credible early church fathers . . . [8]

Jack Finegan noted some early writers’ reckoning . . . [of] 3/2 BC, or 2 BC or later for the birth of Jesus, including Irenaeus (3/2 BC), Clement of Alexandria (3/2 BC), Tertullian (3/2 BC), Julius Africanus (3/2 BC), Hippolytus of Rome (3/2 BC), Hippolytus of Thebes (3/2 BC), Origen (3/2 BC), Eusebius of Caesarea (3/2 BC), Epiphanius of Salamis (3/2 BC), . . . [9, citing #8, pp. 279-292]

Another argument that can be made is the date of coins issued by Herod the Great’s successors. The evidence shows that none can be dated before 1 AD. These coins were controlled by Rome and only after Herod the Great’s death could such coins be issued. It would be odd for a five-year gap to occur. [6: see specific comment] This means that at least three different kinds of argumentation can be made for Herod’s death being later than 4 BC:

1) from an examination of lunar eclipse data as related to the Jewish holidays (based on Josephus’ report), 2) from textual arguments regarding Josephus that reveal a gap of two years compared to the “accepted” chronology, and 3) from the dates of Roman coinage.

As we shall see as we continue this investigation, a tentative acceptance of Herod’s death in 1 BC or 1 AD (if Finegan and others of the same opinion are in fact right) will be very significant in terms of lining up the known astronomical data regarding an extraordinary “bright star” in the sky that can ostensibly or speculatively be equated with the star of Bethlehem.

IV. What Does it Mean to Say that the Star of Bethlehem “Went Before” the Wise Men (Matthew 2:9)?

This refers to (in context) to the wise men being in Jerusalem and talking to Herod (Mt 2:1, 7-9). He “sent them to Bethlehem” (2:8), which is south of Jerusalem, about six miles (I myself traveled this route in 2014). Therefore, this is what the Bible (which habitually uses phenomenological language) means by saying that the star “went before” them. In other words, it would always have been “ahead” or “in front of” or “before” them as they traveled: much as we say we are “following the sun west” or how American slaves (in folklore, at least, if not in fact) attempting to escape to the north followed the “drinking gourd” (the Big Dipper) north. Wikipedia elaborates:

Two of the stars in the Big Dipper line up very closely with and point to Polaris [the North Star]. Polaris is a circumpolar star, and so it is always seen pretty close to the direction of true north. Hence, according to a popular myth, all slaves had to do was look for the Drinking Gourd and follow it to the North Star (Polaris) north to freedom. [11]

Thus, one could say that the Big Dipper or North Star “went before” the slaves, just as we say they “followed” it. The North Star would also lead anyone to the North Pole if they kept following it; that is, by our vantage-point it would “go before” them:

Any astronomer living in the northern hemisphere knows that the North (or Pole) Star appears to be in a fixed position. No matter where a person lives in the northern hemisphere, if they follow a path directly towards the North Star, they will end up at the North Pole. Of course, you would have to be travelling at night to keep your eye on it. [13]

We also refer to the sun “rising” and “setting” as if it is moving. But we know that the appearance of its movement to our eye is due to the earth’s rotation. It’s all phenomenological language, which we use all the time, just as the biblical writers also did. Hence, “The Bible History Guy” writes:

Later that year, in late November to early December of 2 B.C., Jupiter’s position in the sky, when viewed from Jerusalem, was to the south – in the direction of Bethlehem. This was six months after the brilliant birthday conjunction of Jupiter and Venus. This was just the right time for the Magi to reach Jerusalem. [10]

And Wikipedia, in its page on this verse, notes;

The phrase “went before” can mean either that the star was moving throughout their journey or that it remained stationary and served only as a fixed guide. [12]

We know from the astronomical charts that Jupiter was to the south from Jerusalem; therefore, it “went before” the wise men as they traveled south to Bethlehem. The important thing is to understand that it was south in the sky from Jerusalem, heading to Bethlehem, which journey is what the text refers to.

Jupiter wouldn’t have moved much on the way from Jerusalem to Bethlehem. A camel travels about 3 mph average, so it would have taken two hours to get to Bethlehem. That’s roughly the entire time the Bible refers to them (in non-literal language, I believe) following a star. In the language of appearance (non-literal language), it “went before them” not in perceived motion, but because it was always ahead of them on the way.

Dag Kihlman provides an even more fascinating and specific view:

Jupiter — if this was the star of Bethlehem — was not seen in the early evenings in December in 2 BC. It rose very late, at roughly 9 PM. . . .

A more realistic view (if Jupiter was the star of Bethlehem) is that the magi traveled early in the morning, when Jupiter was still visible. . . . In the early morning, Jupiter was south of Jerusalem, and thus in the direction of Bethlehem.

If the magi travelled in the early morning they would probably have followed the normal route between Jerusalem and Bethlehem: Derech Beit Lechem. This route follows the terrain and slowly turns to the west. If the magi started at a suitable hour, they would have had Jupiter in front of them as they left Jerusalem. If they travelled by donkey, camel or horse — slightly faster than the speed of walking — they would have had Jupiter in front of them all the way to Bethlehem, since Jupiter would have moved slowly to the west just as the road slowly turned west. (The Star of Bethlehem and Babylonian Astrology: Astronomy and Revelation Reveal What the Magi Saw, self-published, 2017, pp. 97-98)

V. How Do We Understand the Star of Bethlehem Coming to “Rest Over the Place Where the Child Was”?

“The Bible History Guy” again provides a good summary of what the astronomical data indicate:

On December 2, 2 B.C., Jupiter entered retrograde motion. It continued in this state till December 25 (Julian calendar). During this time, Jupiter appeared to travel horizontally above Bethlehem, when viewed from Jerusalem, while the other planets visible, Mercury and Venus, dipped normally toward the horizon as they traversed the night sky. Jupiter’s horizontal stasis throughout December – right above Bethlehem when viewed from Jerusalem – made it appear to come to rest, as Matthew recorded, above the City of David. After December 25, Jupiter again appeared to behave like other planets, breaking out of its horizontal lock and dipping toward the horizon as it traced the sky. [10]

What is the “retrograde motion” of planets? Astronomer Christopher Crockett explains:

Typically, the planets shift slightly eastward from night to night, drifting slowly against the backdrop of stars. From time to time, however, they change direction. For a few months, they’ll head west before turning back around and resuming their easterly course. Their westward motion is called retrograde motion by astronomers. Though it baffled ancient stargazers, we know now that retrograde motion is an illusion caused by the motion of Earth and these planets around the sun. [14]

As an analogy, when we pass a car on the freeway, it temporarily seems to be moving backwards. As already noted above: in December, 2 BC, Jupiter appeared to come to a stop above Bethlehem and — according to some researchers — remained there seemingly motionless for six days [15]. Ernest L. Martin noted that at dawn on December 25th in that area, it would have been at an elevation of 68 degrees, above the southern horizon: shining down on Bethlehem [17]. It was the brightest “star” in the sky on that day and location. [18]

Matthew 2:9 . . . the star which they had seen in the East went before them, till it came to rest over the place where the child was.

This passage refers only to the six-mile journey between Jerusalem and Bethlehem, and I have contended that all it means is that a bright star (I believe, Jupiter, in my scenario, backed up by astronomical charts of what was in the sky and where) was at the time in the direction of Bethlehem (that is, over it) from Jerusalem. It would not have “moved” in the perception of the wise men, over a journey of six miles, just as we could say we were traveling west, following the setting sun. It would always “go before us” as we traveled.

It’s phenomenological language, which is habitually used by Bible writers. We use it even to this day by referring to the “sun rising” or “sun going down” etc. Literally (as we understand) it is the earth rotating, thus making the sun appear to move. But we still refer to it in the non-literal way. So does the Bible, about a lot of things.

The other aspect is the clause “it came to rest over the place where the child was.” First of all, the text does not say that this means it shone specifically onto a “house.” This is a common misconception. Matthew 2:11 (i.e., two verses later) simply says they went “into a house”: not that the star was shining on it, identifying it. We have to get it straight: what exactly any given text under consideration actually asserts and does not assert. Two of the very best and renowned Protestant Bible commentators and exegetes of our time agree:

It is not said to indicate the precise house, but the general location where the child was. (R. T. France, 1985)

The Greek text does not imply that the star pointed out the house where Jesus was or that it led the travelers through twisty streets; it may simply have hovered over Bethlehem as the Magi approached it. (D. A. Carson, 2017)

Let’s examine the actual biblical text a little more closely. The Greek “adverb of place” in Matthew 2:9 is hou (Strong’s word #3757). In RSV hou is translated by “the place where” (in KJV, simply “where”). It applies to a wide range of meanings beyond something as specific as a house. In other passages in RSV it refers to a mountain (Mt 28:16), Nazareth (Lk 4:16), a village (Lk 24:28), the land of Midian (Acts 7:29), Puteoli (Pozzuoli): a sizeable city in Italy (Acts 28:14), and the vast wilderness that Moses and the Hebrews traveled through (Heb 3:9). Thus it can easily, plausibly refer to “Bethlehem” in Matthew 2:9.

In RSV (Mt 2:9), hou is translated by the italicized words: “it came to rest over the place where the child was.” So the question is: what does it mean by “place” in this instance? What is the star said to be “over”? And then I noted other uses of the same word, which referred to a variety of larger areas. The text does not specifically say that “it stood over a house.” Yet Jonathan (and many able and sincere, but in my opinion mistaken, Christian commentators) seem to think it does.

This is an important point because it goes to the issue of supernatural or natural. A “star” (whatever it is) shining a beam down on one house would be (I agree) supernatural; not any kind of “star” we know of in the natural world. But a star shining on an area; in the direction of an area (which a bright Jupiter was to Bethlehem in my scenario: at 68 degrees in the sky) can be a perfectly natural event.

Matthew 2:9 is similar to how we say in English: “where I was, I could see the conjunction very well.” “Where” obviously refers to a place. And one’s place is many things simultaneously. Thus, when I saw the “star of Bethlehem”-like conjunction in December [2020], I was in a field, near my house (in my neighborhood), in my town (Tecumseh), in my county (Lenawee), in my state (Michigan), and in my country (United States). This is my point about “place” in Matthew 2:9. It can mean larger areas, beyond just “house.” If the text doesn’t say specifically, “the star shone on the house” then we can’t say for sure that this is what the text meant.

I never claimed that hou was a “noun” in my original wording. I was noting that it was referring to place: as indeed it did in Matthew 2:9, since the translation of it in RSV is “the place where.” Therefore “place” is a translation of hou in this instance.

I have found 18 other English Bible translations of Matthew 2:9 that also have “the place where” (Weymouth, Moffatt, Confraternity, Knox, NEB, REB, NRSV, Lamsa, Amplified, Phillips, TEV, NIV, Jerusalem, Williams, Beck, NAB, Kleist & Lilly, and Goodspeed). In all these cases, they are translating hou: literally meaning “where” but at the same time implying place (which is the “where” referred to). The Living Bible (a very modern paraphrase) has “standing over Bethlehem”: which of course, bolsters my argument as well (because it didn’t say “house”).

All these things being understood, all the text in question plausibly meant is that the bright star was shining down on Bethlehem, just as we have all seen the moon or some bright star shining on a mountain in the distance or tall building or some other landmark. A man might see the light from the harvest moon romantically shining on his girlfriend or wife’s face. It need not necessarily mean that this is all they are shining on. It simply looks that way from our particular vantage-point.

But technically, the text doesn’t specify a “small area” being illuminated, or even a larger one. All the actual text says is “the star which they had seen in the East went before them, till it came to rest over the place where the child was” (Matthew 2:9, RSV). And as I have shown, all that has to mean, given the use of the word hou in the New Testament is: “the star stood over Bethlehem”: particularly from the vantage point of the journey south from Jerusalem to Bethlehem.

All of this is in my opinion, more plausible and straightforward and in line with biblical thinking than positing a supernatural “star.” It’s true that many reputable and observant Christian biblical commentators exist who do argue for that interpretation, and I don’t disparage them. Theirs are honest efforts just as this paper is. Reasonable people can and do disagree. I can only present the reasons for why I hold to my opinion, and for why assertions (from atheists like Jonathan MS Pearce and author of a negative book on the star: Aaron Adair) of a necessary or exclusively plausible supernatural nature of the star of Bethlehem are less reasonable and likely than my scenario.

Thus it can easily, plausibly refer to “Bethlehem” in Matthew 2:9. It may be that many readers (filled with the endless – sometimes inaccurate — images of Christmas from childhood) confuse this with another Christmas passage:

Luke 2:8-9 And in that region there were shepherds out in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night. [9] And an angel of the Lord appeared to them, and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were filled with fear.

Note that even in this passage, it is the light from an angel (rather than a star) that “shone around them” and they were not yet visiting Jesus. Thus, Luke 2:15 states: “Let us go over to Bethlehem and see this thing that has happened . . .” They were not in the same place. When I visited Bethlehem in 2014, I saw exactly how far it was: at least according to local tradition. The birth site is quite a ways off by sight, and at a higher elevation. We mustn’t be led astray by extraneous factors when exegeting Holy Scripture. I believe the explanation I have adopted is plausible and in complete harmony with both science and the biblical texts.

To say, then, that the star “came to rest over the place” is to observe that they didn’t see it moving much over Bethlehem once they arrived there. I’m not an astronomer, so I can only cite other people who know more about these aspects.

The EarthSky site (“Jupiter ends retrograde on July 10-11”) notes regarding Jupiter’s stationary point in July 10-11, 2018:

Tonight – July 10-11, 2018 – the planet Jupiter is poised in front of the stars of the zodiac. It’s now moving neither east nor west against the star background, but will soon resume its usual eastward course. In other words, Jupiter is stationary on July 11 at 04:00 UTC. In United States time zones, Jupiter reaches its stationary point on July 11 at 12 midnight EDT, and on July 10 at 11 p.m. CDT, 10 p.m. MDT, 9 p.m. PDT, 8 p.m. Alaskan Time and 6 p.m. Hawaiian time.

So in my scenario, this was the case in Bethlehem when the Magi arrived. This is what would have looked to them like “[coming] to rest over” Bethlehem. The astronomical charts show this for one of the days in December, 2 BC. That’s my proposed date for their visit. Of course it could be wrong and is only speculation, but Jupiter would behave in this way then.

The Wikipedia article, “Apparent retrograde motion” provides another example:

Galileo’s drawings show that he first observed Neptune on December 28, 1612, and again on January 27, 1613. On both occasions, Galileo mistook Neptune for a fixed star when it appeared very close—in conjunction—to Jupiter in the night sky, hence, he is not credited with Neptune’s discovery. During the period of his first observation in December 1612, Neptune was stationary in the sky because it had just turned retrograde that very day. Since Neptune was only beginning its yearly retrograde cycle, the motion of the planet was far too slight to be detected with Galileo’s small telescope.

That’s lack of motion, and that is what I and others suggest was happening with Jupiter over Bethlehem when the wise men visited, thus bringing about the Bible’s statement that it “came to rest over the place where the child was” (Mt 2:9, RSV). Thus, the language of appearance can explain both clauses: the one just mentioned and also “went before them”, and can be harmonized with celestial events in the way I have explained.

If the wise men hit the right day, Jupiter would have appeared to be stationary, just as Neptune was for Galileo in December 1612 “because it had just turned retrograde that very day.” I didn’t make this stuff up. I had never heard about it till last month when I saw the famous Larson video on the star. But it has fascinated me ever since and it’s my theory unless and until I see something more plausible.

In the Christian view, God in His providence could have again arranged that the wise men, exercising their own free will, arrived at just the right time when the bright Jupiter appeared to be a sign above Jerusalem, for this king they believed was indicated by what they saw in Persia or Babylon (both due east).

Commentator Peter Pett stated that Jupiter “was actually stationary on December 25, interestingly enough, during Hanukkah, the season for giving presents.” That was in 2 BC. Note again that I am not saying this is when Jesus was born, but rather, when He was a year old. Just as the trek to Bethlehem may have taken only 18 or so minutes, likewise, their visit to Jesus may have been very short, for all we know. The overall passage may imply that they left quickly, to avoid a return visit to Herod: going back another way: which I think was either the coastal route west and north or straight through the desert to the east.

But say they were only there two hours. They would have seen very little motion of Jupiter in that time because of its being stationary, and so again, it would be perfectly harmonious with the clause “came to rest over the place where the child was”. Phenomenological language describing natural events all the way . . . That’s my theory.

Ivor Bulmer-Thomas, in his article, “Star of Bethlehem” (Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 33, Dec. 1992) opined:

As a planet approaches a stationary point and then moves away from it its motion is very slow, hardly detectable by the naked eye for about a week. The Magi would have noticed the slowing down of the planet as they approached Bethlehem, and they would have recognized that a stationary point was near. (p. 371)

Now what is even more interesting is Bulmer-Thomas’ documentation that the ancients knew about retrograde motion of the planets, and stationary points:

[T]here is a wealth of material showing directly that for several centuries before the birth of Christ and round about the time of his birth Babylonian astronomers were deeply interested in retrogradations and stationary points. It is contained in hundreds of cuneiform texts excavated in Babylon and Uruk . . . The three volumes of Neugebauer’s Astronomical Cuneiform Texts (1955) give a vast collection of Babylonian inscriptions dealing with retrogradations and stations. (p. 370)

This is highly significant because it would mean not only that Matthew 2:9 uses phenomenological language, but also that the Magi understood retrograde motion of planets, which may lie behind the terminology (received from oral tradition) of “came to rest over” Bethlehem.

And in my opinion these facts support my natural interpretation all the more, because it’s not just (as a critic might say) “projecting” our modern scientific understanding onto the Bible, but an understanding that already existed and was known by the Wise Men.

Dag Kihlman again puts all these considerations together in a fascinating way, as to the star having “stood over” Bethlehem:

[T]he magi did study when the planets reached their stationary point, that is, when they made a halt. In fact, that was one of the main things the magi studied (see Chapter 2.4).

[Atheist anti-star polemicist Aaron] Adair’s mistake is that to him, a halt is a speed of exactly zero metres per second — that is, no movement at all. This is a halt in the modern mind, but the magi did not have such precision. They used their fingers to study the movements of planets, and when they could not measure a movement (because it was moving so slowly), they reached the conclusion that the planet had halted. . . . they had used this rule for centuries as they recorded the stationary points on a regular basis. Adair’s line of reasoning thus misses the point completely. (ibid., p. 98)

VI. Lining Up the Stars in the Heavens in 3-2 BC

Christians who have written about this have previously mostly concentrated on celestial events in the years 7-5 BC, based on the assumption of Herod’s death in 4 BC. But if he in fact died in 1 BC or 1 AD (not claiming that it’s certain; but based on more or less plausible scholarly speculation), then we should look instead to the events of 3-1 BC, when Jesus would then be born. “The Bible History Guy” provides a pretty good summary of what we will examine next:

Between September of 3 B.C. and May of 2 B.C., Jupiter, the king of planets, viewed from Babylon, made three conjunctions with Regulus, the star that the Romans called rex and the Persians called sharu– king. Jupiter approached Regulus and conjoined with it in the night sky, creating a bright light. This was unusual, but not unique, since Jupiter conjoins with Regulus about every twelve years. But after passing Regulus, Jupiter turned around (entered retrograde motion) and passed over Regulus again. Then it turned around again and repeated the performance a third time. Three crossings of the king planet and the king star – with three brilliant flashes in the night sky – were startling and unique. The Magi took note. . . . On Wednesday, June 17, 2 B.C., after completing its triple conjunction with Regulus, Jupiter, the King Planet, continued through the heavens to another spectacular rendezvous, this time with Venus, the Mother Planet. They appeared to touch, and each contributed its full brightness to what seemed like the most brilliant star anyone had ever seen. The conjunction reached its apex as the two planets set in the west, right over Judea from the perspective of the Babylonian Magi. This was the Birth Star, the Star of Bethlehem. . . . [10]

Wikipedia [9] briefly describes the opinions of attorney Frederick Larson, who produced the much-viewed video documentary The Star of Bethlehem in 2007:

Highlights include a triple conjunction of Jupiter, called the king planet, with the fixed star Regulus, called the king star, starting in September 3 BC. . . . By June of 2 BC, nine months later, . . . Jupiter had continued moving in its orbit around the sun and appeared in close conjunction with Venus in June of 2 BC. . . . Astronomer Dave Reneke independently found the June 2 BC planetary conjunction, and noted it would have appeared as a “bright beacon of light”.[93] Jupiter next continued to move and then it stopped in its apparent retrograde motion on December 25 of 2 BC over the town of Bethlehem.

Astronomer Craig Chester provides his take on all these celestial events:

In September of 3 B.C., Jupiter came into conjunction with Regulus, the star of kingship, the brightest star in the constellation of Leo. Leo was the constellation of kings, and it was associated with the Lion of Judah. The royal planet approached the royal star in the royal constellation representing Israel. Just a month earlier, Jupiter and Venus, the Mother planet, had almost seemed to touch each other in another Close conjunction, also in Leo. Then the conjunction between Jupiter and Regulus was repeated, not once but twice, in February and May of 2 B.C. Finally, in June of 2 B.C., Jupiter and Venus, the two brightest objects in the sky save the sun and the moon, experienced an even closer encounter when their disks appeared to touch; to the naked eye they became a single object above the setting sun. This exceptionally rare spectacle could not have been missed by the Magi. In fact, we have seen here only the highlights of an impressive series of planetary motions and conjunctions fraught with a variety of astrological meanings, involving all the other known planets of the period, Mercury, Mars, and Saturn. [16]

I provided biblical and historical arguments for Jesus being born on December 25th, in a previous article (12-11-17). That can easily be harmonized with the present analysis. John the Baptist (according to the arguments I presented there) would have been conceived in late September, 4 BC and born in late June, 3 BC, while Jesus (six months younger: Lk 1:36) was conceived around 25 March, 3 BC (the Annunciation) and born on 25 December, 3 BC. Meanwhile, Jupiter was in a very close conjunction with Venus on 17 June, 2 BC: so close they may have even overlapped. It would have looked to the naked eye like one very bright star: about as close as any conjunction can be. This would have (plausibly) enticed the Magi to journey to Jerusalem, partially because it would have appeared in the west, precisely in that direction [17]. Moreover on 26-27 August in 2 BC, Jupiter and Mars were in very close conjunction, and Venus and Mercury were also close by [17].

In December, 2 BC (possibly on December 25th), the wise men arrived and visited Jesus in Bethlehem, when He was (by my previous “biblical calculations”) about a year old. Jupiter was right above Bethlehem in December (viewed from Jerusalem), in its paused retrograde motion (and seeming not to move at all for six days). Thus, we possibly have the wise men visiting Jesus on the date later recognized as Christmas, or at least in the month of December, but without Jesus being a newborn baby: which lines up with patristic thought. In that year, the feast of Hanukkah began on December 23rd. It’s a gift-giving feast. They would have observed the entire Jewish nation in a happy holiday spirit. The wise men, if they saw Jesus on the 25th, would in turn have presented gifts to him on the third day of the festival. [17]

It’s believed from the astronomical data that Jupiter began “moving” again after 25 December, 2 BC. That fits into the notion of the star of Bethlehem guiding the wise men. Since they found Jesus on or before December 25th, they no longer needed to be guided by what they believed was a “sign” or “guide” for them. One can apply statistical analysis to all this, too, in order to illustrate how rare these events were (Martin’s data is utilized):

How rare is the sequence of events we are considering here? As noted above, this will depend on the separation of Jupiter and Venus at the close conjunction of 17 June 2 BC. . . . With Martin’s separation of 0.5 minute, it will occur about once every 6923 years. The event is seen to be even rarer when we add in the triple conjunction of Jupiter with Regulus, which only occurs in this particular year because the eleven degree wide loop made by Jupiter at opposition happens to lie across the position of Regulus. . . . the frequency of this close Jupiter-Venus conjunction plus the triple conjunction with Regulus can be expected to happen . . . every 228 thousand years (Martin), . . . A rare event indeed! [19]

However one comes down on these issues, it certainly is a very fascinating topic: one of the most intriguing I’ve ever written about in my nearly 40 years of apologetics. And all of this confirms what the Bible (God’s inspired and infallible revelation) has taught all these years. Science has not “refuted” the Bible. It’s quite the opposite: it confirms and verifies it again and again.

Sources

1) “Magi, The”, International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, James Orr, general editor, 1915.

2) “Magi”, The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1910.

3) “Camel Fact Sheet”, PBS, 9-17-20.

4) “Who Were the Magi (Three Wise Men) that visited Christ?”, Christianity.com, 4-12-10.

5) “Magi”, New Bible Dictionary, J. D. Douglas, general editor, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1962, pp. 765-766.

6) “Herod’s Death, Jesus’ Birth and a Lunar Eclipse: Letters to the Editor debate dates of Herod’s death and Jesus’ birth”, Bible History Daily / Biblical Archaeology Society, 11-30-20 / originally 1-7-15.

7) “Common Errors in ‘Star of Bethlehem’ Planetarium Shows”, John Mosley, Planetarian, Third Quarter 1981.

8) Jack Finegan, Handbook of Biblical Chronology, Hendrickson, Grand Rapids, Michigan: 1998, pp. 298-299. This citation is quoted on the page, “When did King Herod the Great reign and die?”, Never Thirsty.

9) “Star of Bethlehem”, Wikipedia.

10) “The Real Star of Bethlehem”, The Bible History Guy, 12-12-19.

11) “Follow the Drinkin’ Gourd”, Wikipedia.

12) “Matthew 2:9”, Wikipedia.

13) “Did the Magi follow a moving star or did they have two sightings in Matthew 2:2 and 2:9?”, Biblical Hermeneutics, answer of 5-31-18.

14) “What is retrograde motion?”, Christopher Crockett, EarthSky, 2-6-17.

15) “The Star of Bethlehem: An Astronomical and Historical Perspective”, Susan S. Carroll, 1997.

16) “The Star of Bethlehem”, Craig Chester, Imprimus, December 1993.

17) Ernest L. Martin, The Star That Astonished the World, published in 1991; available online at Associates for Scriptural Knowledge.

18) “Star of Bethlehem”, Ronald E. Mickle, 2003.

19) “The Star of Bethlehem: A Natural-Supernatural Hybrid?”, Robert C. Newman, 2001.

20) “Bethlehem, Star of”, Michele Crudele, Interdisciplinary Encyclopedia of Religion and Science, 2002.

***

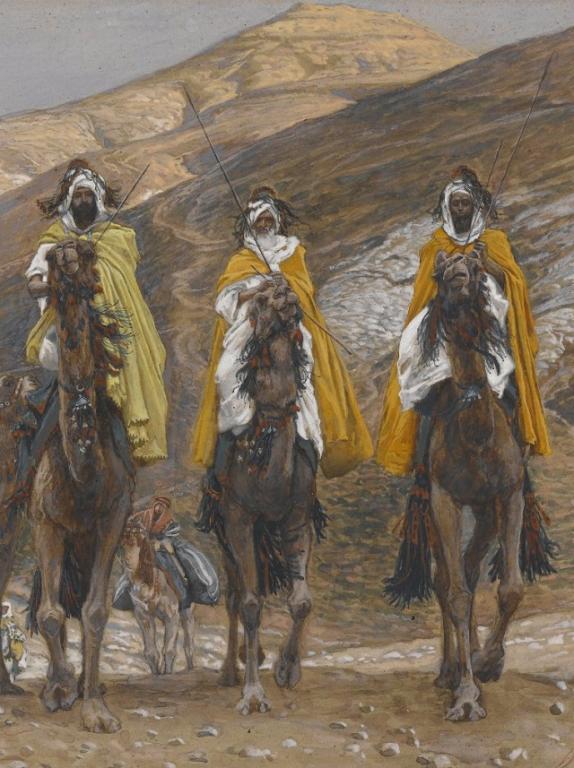

Photo credit: The Magi Journeying (portion), by James Tissot (1836-1902) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***