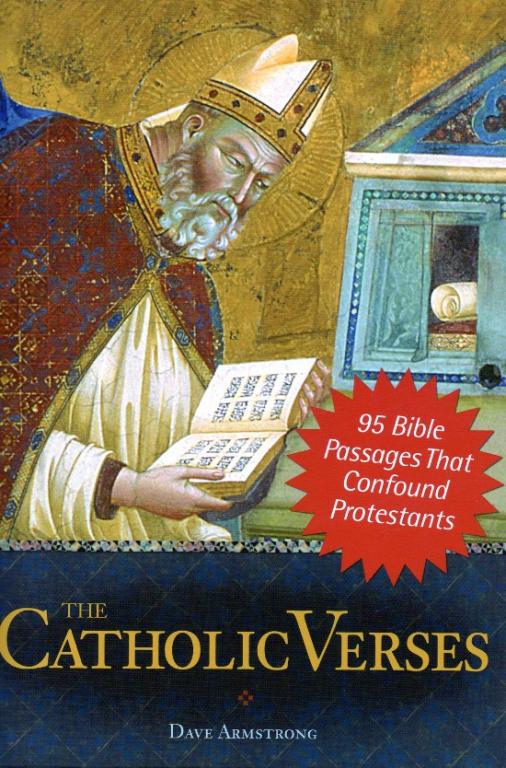

[Book and purchase information]

Revelation 5:8 (RSV) And when he had taken the scroll, the four living creatures and the twenty-four elders fell down before the Lamb, each holding a harp, and with golden bowls full of incense, which are the prayers of the saints;

Revelation 6:9-10 When he opened the fifth seal, I saw under the altar the souls of those who had been slain for the word of God and for the witness they had borne; they cried out with a loud voice, ‘O Sovereign Lord, holy and true, how long before thou wilt judge and avenge our blood on those who dwell upon the earth?’

Revelation 8:3-4 And another angel came and stood at the altar with a golden censer; and he was given much incense to mingle with the prayers of all the saints upon the golden altar before the throne; and the smoke of the incense rose with the prayers of the saints from the hand of the angel before God.

Matthew 17:1-3 And after six days Jesus took with him Peter and James and John his brother, and led them up a high mountain apart. And he was transfigured before them, and his face shone like the sun, and his garments became white as light. And behold, there appeared to them Moses and Elijah, talking with him.

Matthew 27:52-53 the tombs also were opened, and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised, and coming out of the tombs after his resurrection they went into the holy city and appeared to many.

Catholics believe that saints and angels in heaven can pray for us on earth and can hear our intercessory requests, just as people on earth can do; in fact, being so near to God’s presence in heaven, their prayers are more powerful than ours on earth. But most Evangelical Protestants today would deny the saints’ intercessory power – and thus claim that any attempt to petition them would be vain at best and idolatrous at worst – as placing superfluous additional mediators between God and mankind.

There is, again, some agreement with the Catholic position among the founders of Protestantism. Martin Luther, in his Smalcald Articles of 1537, acknowledged that saints in heaven “perhaps” pray for those on earth, although he denies that they can be invoked or asked to offer prayer:

Although angels in heaven pray for us (as Christ himself also does), and although saints on earth, and perhaps also in heaven, do likewise, it does not follow that we should invoke angels and saints (Part II, Article II, in Tappert, 297).

John Calvin takes a similar view:

They again object, Are those, then, to be deprived of every pious wish, who, during the whole course of their lives, breathed nothing but piety and mercy? . . . [T]here cannot be a doubt that their charity is confined to the communion of Christ’s body, and extends no farther than is compatible with the nature of that communion. But though I grant that in this way they pray for us, they do not, however, lose their quiescence so as to be distracted with earthly cares: far less are they, therefore, to be invoked by us (Institutes, III, 20, 24; emphasis added).

But Calvin continues in the same section, speaking much more like present-day Protestants:

But all such reasons are inapplicable to the dead, with whom the Lord, in withdrawing them from our society, has left us no means of intercourse (Eccles. 9:5, 6), and to whom, so far as we can conjecture, he has left no means of intercourse with us.

Biblical evidence to the contrary was discussed in the preceding section. As for the dead being “withdrawn” from earthly concerns, I would ask Calvin if he were here today: “Why, then, are there so many instances of the dead in Christ having contact with the living, with the full consent of God?”

Some examples of this are Moses and Elijah appearing with Jesus at the Transfiguration (Matt. 17:1-3), the “two witnesses” of Revelation 11:3, whom many commentators believe to be Moses and Elijah also; Samuel’s appearance to Saul, prophesying his impending death (1 Sam. 28:12, 14-15; commentators are almost unanimous in asserting that this was actually Samuel); and the many saints who rose from the dead and appeared to many in Jerusalem after Jesus’ death (Matt. 27:52-53).

Calvin contradicts himself, however, shortly after he granted that saints in heaven pray for us:

[T]he dead, of whom we nowhere read that they were commanded to pray for us. The Scripture often exhorts us to offer up mutual prayers; but says not one syllable concerning the dead . . . While the Scripture abounds in various forms of prayer, we find no example of this intercession (Institutes, III, 20, 27; emphasis added).

Elsewhere, he says flatly:

Of purgatory, the intercession of saints . . . not one syllable can be found in Scripture (Institutes, IV, 9, 14).

It is seldom wise to make such sweeping negative statements, because just one counterexample can make them look rather foolish. The counterproof to Calvin’s statement lies in the three passages from Revelation cited in this section. Calvin attempts another sort of disproof by claiming that to say the saints intercede for us is to confuse men and angels on the order of being:

We frequently read (they say) of the prayers of angels, and not only so, but the prayers of believers are said to be carried into the presence of God by their hands . . . How preposterously they confound departed saints with angels is sufficiently apparent from the many different offices by which Scripture distinguishes the one from the other (Institutes, III, 20, 23).

This is frivolous logic. All that has to be shown as a commonality is the capacity to intercede. Dead saints do not have to have all the characteristics of angels to do that. Calvin’s reasoning is as absurd as the following analogy:

- A great intellect like Einstein’s abilities include the knowledge that 2 + 2 = 4.

- A child of six also knows that 2 + 2 = 4.

- But in order for a child to know that, he must have all of Einstein’s knowledge.

- Therefore, the child cannot know that 2 + 2 = 4 because he doesn’t have all of Einstein’s knowledge.

The false premise obviously lies in proposition number three. Likewise, Calvin’s false premise is his implied assumption that saints would need to be like angels in all respects in order to intercede. Apart from the faulty reasoning, Scripture clearly contradicts the assertion, anyway, for Revelation 8:3-4 describes an angel presenting the prayers of the saints to God, and Revelation 5:8 attributes to human beings the same function.

How does Calvin interpret these passages? It’s difficult to determine, because he did not comment on them in the Institutes (except for one veiled, ambiguous reference above), and did not write a commentary on Revelation. So we will have to examine how other Protestants deal with this fascinating biblical data. Methodists Adam Clarke and John Wesley in their commentaries simply make the prayers presented in 5:8 figurative. Clarke makes a rather curious assertion concerning Revelation 8:3-4:

It is not said that the angel presents these prayers. He presents the incense, and the prayers ascend with it.

But the incense is the prayers of the saints in Revelation 5:8, making Clarke’s contention implausible. Jamieson, Fausset, and Brown do some eisegesis of their own in commenting on 8:3-4 (capitalization in original):

How precisely their ministry, in perfuming the prayers of the saints and offering them on the altar of incense, is exercised, we know not, but we do know they are not to be prayed TO . . . It is not the saints who give the angel the incense; nor are their prayers identified with the incense; nor do they offer their prayers to him. Christ alone is the Mediator through whom, and to whom, prayer is to be offered.

How, indeed, do we know the angels are not asked to intercede? For it stands to reason that they would be offering the prayers of the saints only if they were asked to – otherwise those prayers would not be, in a sense, theirs to offer.

Lastly, the fact that Christ is mediator is not questioned by anyone. Asking a saint in heaven to pray for us no more interferes with the unique mediation of Christ than does asking a person on earth to pray for us. We always pray in Christ, through His power, and to Him, whether it is directly to Him, or by means of another person or angel, in heaven or on earth.

The (false) dichotomy between Christ’s mediation and human or angelic mediation need not be drawn at all; it arises only because of the Protestant’s needless alarmism at God’s making use of creatures to fulfill his purposes. Jamieson, Fausset, and Brown’s comment on Revelation 5:8 exhibits even more of a sort of “fortress mentality”:

This gives not the least sanction to Rome’s dogma of our praying to saints. Though they be employed by God in some way unknown to us to present our prayers (nothing is said of their interceding for us), yet we are told to pray only to Him (Rev. 19:10; 22:8, 9).

We are not told in Scripture that we cannot ask someone in heaven to pray for us. Saints in heaven are more alive and aware and far more holy than we are. They watch us (Heb. 12:1). They are aware of earthly happenings (Rev. 6:9-10). They can certainly be given extraordinary capacities for knowledge by God; there is nothing implausible or intrinsically impossible or unbiblical in that notion at all.

St. Paul states about the afterlife in heaven:

1 Corinthians 13:12 For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall understand fully, even as I have been fully understood.

Therefore, they can pray for us and we can ask for their prayers. We know that they can come back to earth (from the four examples given earlier). Are we to believe that when such saints come to earth they can pray, but immediately upon returning to heaven they cannot once again? And if they can present our prayers, why is it so inconceivable that they could intercede for us?

Albert Barnes in his comment on both Revelation 5:8 and 8:3 draws some hairsplitting distinctions that would make the most skillful lawyer envious:

The representation there [Revelation 8:3] undoubtedly is, that the angel is employed in presenting the prayers of the saints which were offered on earth before the throne. It is most natural to interpret the passage before us [Revelation 5:8] in the same way . . . It is not said that they offer the prayers themselves, but that they offer incense as representing the prayers of the saints.

Much more sensible and plausible is part of his comment on Revelation 6:9-10:

The souls of them that were slain. That had been put to death by persecution. This is one of the incidental proofs in the Bible that the soul does not cease to exist at death, and also that it does not cease to be conscious, or does not sleep till the resurrection. These souls of the martyrs are represented as still in existence; as remembering what had occurred on the earth; as interested in what was now taking place; as engaged in prayer; and as manifesting earnest desires for the Divine interposition to avenge the wrongs which they had suffered.

But then, Barnes’ Protestant bias comes over him again:

[N]or are we to suppose that the injured and the wronged in heaven actually pray for vengeance on those who wronged them, or that the redeemed in heaven will continue to pray with reference to things on the earth; but it may be fairly inferred from this that there will be as real a remembrance of the wrongs of the persecuted, the injured, and the oppressed, as if such prayer were offered there.

Peter Berger, an eminent Lutheran sociologist, discusses with great insight the difference between Protestantism and Catholicism, with regard to the Communion of Saints:

If compared with the “fullness” of the Catholic universe, Protestantism appears as a radical truncation, a reduction to “essentials” at the expense of a vast wealth of religious contents . . . Protestantism may be described in terms of an immense shrinkage in the scope of the sacred in reality, as compared with its Catholic adversary . . . The immense network of intercession that unites the Catholic in this world with the saints and, indeed, with all departed souls disappears as well. Protestantism ceased praying for the dead.

The Catholic lives in a world in which the sacred is mediated to him through a variety of channels — the sacraments of the church, the intercession of the saints, the recurring eruption of the “supernatural” in miracles — a vast continuity of being between the seen and the unseen. Protestantism abolished most of these mediations. It broke the continuity, cut the umbilical cord between heaven and earth (Berger, 111-112).

Protestants are very reluctant to speak about these departed saints at all, on the grounds that it somehow raises them to a “godlike” status or detract from God’s sole glory and majesty; or perhaps that it would lead them dangerously close to necromancy. As we have seen, this runs contrary to much biblical indication otherwise.

In this, as in so many instances, I believe that the underlying negative or skeptical attitude is rooted in a fear or suspicion that to act in “Catholic” ways would be to yield ground to Catholics and to start down a slippery slope leading inexorably to Rome. It is a defensive “fortress mentality.” But I would contend that all Christians must yield to the biblical examples and commands, whether the issue at hand outwardly appears “Protestant” or “Catholic.”

Catholics who venture out into the ground of apologetics and sharing their faith with Protestants will encounter this attitude over and over, and need to be aware of how to counter it with solid biblical argumentation and simple logic. As Peter Berger noted above, Protestantism is characterized by “an immense shrinkage in the scope of the sacred in reality.”

The mysterious, the miraculous, the sacramental, and other similar elements are minimized in many sectors of Protestantism. The overwhelming emphasis is on the individual in relationship to God, and the “Word” (construed as the Bible Alone). That is simply not in accord with the Bible and historical Christianity. Therefore, Catholics who try to defend these beliefs need to show that they are rooted in the Bible, not merely petrified and arbitrary “[Catholic] traditions of men.”

***

SOURCES

Barnes, Albert [Presbyterian], Barnes’ Notes on the New Testament, 1872; reprinted by Baker Book House (Grand Rapids, Michigan), 1983. Available online.

Berger, Peter L., The Sacred Canopy, Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1967.

Calvin, John, Institutes of the Christian Religion, translated by Henry Beveridge for the Calvin Translation Society, 1845 from the 1559 edition in Latin. Reprinted by Eerdmans Pub. Co. (Grand Rapids, Michigan), 1995. Available online. (see also the 1960 translation listed under McNeill)

Clarke, Adam [Methodist], Commentary on the Bible, 1825, six volumes; reprinted by Abingdon Press (Nashville), no date. An abridged one-volume edition by Ralph Earle was published by Baker Book House (Grand Rapids, MI), 1967. Available online.

Jamieson, Robert [Presbyterian], Andrew R. Fausset [Anglican], and David Brown [Anglican], Commentary on the Whole Bible, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 1961 (orig. 1864). Available online.

Tappert, Theodore G., translator and editor, The Book of Concord, St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1959. [A different translation is available online]

***

*

My book royalties from three bestsellers in the field (published in 2003-2007) have been decreasing, as has my overall income, making it increasingly difficult to make ends meet. I provide over 2500 free articles here, for the purpose of your edification and education, and have written 50 books. It’ll literally be a struggle to survive financially until Dec. 2020, when both my wife and I will start receiving Social Security. If you cannot contribute, I ask for your prayers. Thanks! See my information on how to donate (including 100% tax-deductible donations). It’s very simple to contribute to my apostolate via PayPal, if a tax deduction is not needed (my “business name” there is called “Catholic Used Book Service,” from my old bookselling days 17 or so years ago, but send to my email: [email protected]). May God abundantly bless you.

***

(originally 2004)

***