This is a continuing reply to the arguments of James White: from his oral debate with Gerry Matatics (article posted on 13 November 1992: transcript of the debate that took place on 11-13-92). I will be replying point-by-point to White’s arguments: which virtually never occurs in oral debates such as this. For background, see my reply to White’s Opening Argument (#2 in this series).

See my Introduction to what will be a very long series (and the other installments). Words of James White will be in blue.

*****

First Rebuttal

And I do stand under the authority of the Word of God and if it can be demonstrated from the Word of God that what I believe is untrue than I will most assuredly follow in that direction.

Great! Then if White ever reads this, he’ll be in a good position to change his mind, because I’m giving him tons of Scripture (far more than he has provided thus far), and it is all in the direction of Catholicism, not his Reformed Baptist Calvinism.

II Timothy 1:13-14, Paul, writing to Timothy says–the same passage in which he says, “Pass on what I have spoken to you,”–“What you heard from me, keep as the pattern of sound teaching, with faith and love in Christ Jesus. Guard the good deposit that was entrusted to you–guard it with the help of the Holy Spirit who lives in us.” This is what he is to be passing on. The pattern of sound doctrine, the pattern of sound words. And that certainly is what we have in the New Testament is that pattern of sound words. Look at I Timothy 6:20-21, “Timothy, guard what has been entrusted to your care. Turn away from godless chatter and the opposing ideas of what is falsely called knowledge, which some profess and in so doing have wandered from the faith.” This is not something different than what you have in Romans or Galatians. This is not something about Immaculate Conception. This is not some oral tradition that exists separately from the New Testament at all. [my added bolding]

The problem — again — is that Paul was not referring to the New Testament, which wasn’t yet all written at this time. White simply makes the assumption that he is doing that, based on? . . . well, nothing. It’s his Protestant principle of “inscripturation”, which means, in his usage, that any oral tradition (which he acknowledges, existed) floating around before the Bible was written and/or canonized would have to either make it into Scripture itself or else be discarded as of no import and authority. Conservative Bible scholars date 2 Timothy to the middle 60s. The Gospel of John wasn’t written until probably 80-85 at the earliest.

At this early period, according to conservative Protestant Bible scholars (folks like the New Bible Dictionary and Norman Geisler), the book of Acts was scarcely known or quoted, and Hebrews, James, 1 and 2 Peter, 1, 2, and 3 John, Jude, and Revelation were all not considered to be part of the biblical canon. Thus, this tradition that Paul was passing on to Timothy, did not include at least ten New Testament books. Even the Synoptic Gospels were just being written around the same time (let alone being spread around by then).

James White is living in a fantasy world, immune to historical facts, when he argues like this. It’s blind faith, and be gone with serious historical analysis of the dates of the writing of New Testament books and also dates for wide acceptance and canonization of each one. The first person we know of who listed all 27 New Testament books is St. Athanasius in 367: which was three centuries after the time that Paul wrote his second epistle to Timothy. So to argue that all Paul is referring to is what we have in the New Testament, and only could be that, is patently ridiculous, and based on no evidence whatsoever. This is why White provides no biblical or historical evidence for these sorts of wild assumptions: because there is none.

Look at II Thessalonians 3:6, if you want to see some other passages where Paul discusses this very thing. I don’t hear too many pages turning out there. II Thessalonians 3:6, “In the name of the Lord Jesus Christ we command you, brothers, to keep away from every brother who is idle and does not live according to the teaching you received from us.” Well, here it is again. NIV uses “teaching,” other translations use “tradition.” Well, where did this tradition come from? Is this some tradition that exists outside the New Testament? No! Look back at I Thessalonians 4:1-2. “Finally, brothers, we instructed you how to live in order to please God, as in fact you are living. Now we ask and urge you in the Lord Jesus to do this more and more. For you know what instructions we gave you by the authority of the Lord Jesus.” We are not talking about something that exists separately from the New Testament that is different and in fact that the Church does not even find out about for many, many centuries after they were supposedly delivered.

We agree that whatever it is, it is harmonious with New Testament teaching. White’s error is in his equating it with the New Testament. There is simply no evidence for that. Therefore, he gives none. He cites a passage that he seems to think supports this thesis, but it does not at all. It provides nothing within a million miles of this “inscripturation” thesis.

I would like to read just a few passages for you. For example, when the great early Father, Augustine, long after the Council of Nicaea, wrote a letter to Maximun, the Arian. Again, here come the Arians again. Why is that important? Well, because the Arians deny a very central foundational doctrine of faith, the deity of Christ. When he wrote to Maximun, the Arian, he knew that Maximun could cause him some problems. Do you know why? Because there were church councils held during the Arian ascendancy that denied the deity of Christ. Sermium, Arminum, church councils that erred, that made mistakes on that subject. And so what did Augustine say? “I must not press the authority of Nicaea against you, nor you that of Arminum against me. I do not acknowledge the one as you do not the other. But let us come to ground that is common to both, the testimony of the Holy Scriptures.” Where is the oral tradition? Why don’t we say, “Well, oral tradition teaches the deity of Christ, and you must bow to it.” That’s not what he does. He argues from Scripture to demonstrate that.

Augustine, again, “Let us not hear, ‘This I say, this you say’ but ‘Thus says the Lord.’ Surely it is the books of the Lord on whose authority we both agree and on which we both believe. Therefore, let us seek the church. There let us discuss our case in the Scriptures.”

This is absurd, and doesn’t prove at all that Augustine was denying the supreme authority of ecumenical councils. All it shows — and very clearly so — is that he knew the Arians wouldn’t acknowledge its authority; therefore, he didn’t use it to press his argument. He used Scripture because the Arians accepted its authority: precisely the same reason I have an overwhelming biblical focus in my counter-Protestant apologetics efforts (it’s one thing I’m most know for: one of my trademarks). Augustine explains exactly why he did so, by saying, “let us come to ground that is common to both” and “on whose authority we both agree”. We know that St. Augustine’s rule of faith was thoroughly Catholic, not Protestant. I documented this in August 2003. Here are a few highlights (bolding added presently):

As to those other things which we hold on the authority, not of Scripture, but of tradition, and which are observed throughout the whole world, it may be understood that they are held as approved and instituted either by the apostles themselves, or by plenary Councils, whose authority in the Church is most useful, . . .For often have I perceived, with extreme sorrow, many disquietudes caused to weak brethren by the contentious pertinacity or superstitious vacillation of some who, in matters of this kind, which do not admit of final decision by the authority of Holy Scripture, or by the tradition of the universal Church. (Letter to Januarius, 54, 1, 1; 54, 2, 3; cf. NPNF I, I:301)

I believe that this practice [of not rebaptizing heretics and schismatics] comes from apostolic tradition, just as so many other practices not found in their writings nor in the councils of their successors, but which, because they are kept by the whole Church everywhere, are believed to have been commanded and handed down by the Apostles themselves. (On Baptism, 2, 7, 12; from William A. Jurgens, editor and translator, The Faith of the Early Fathers, 3 volumes, Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 1970, vol. 3: 66; cf. NPNF I, IV:430)

. . . the custom, which is opposed to Cyprian, may be supposed to have had its origin in apostolic tradition, just as there are many things which are observed by the whole Church, and therefore are fairly held to have been enjoined by the apostles, which yet are not mentioned in their writings. (On Baptism, 5,23:31, in NPNF I, IV:475)

The Christians of Carthage have an excellent name for the sacraments, when they say that baptism is nothing else than “salvation” and the sacrament of the body of Christ nothing else than “life.” Whence, however, was this derived, but from that primitive, as I suppose, and apostolic tradition, by which the Churches of Christ maintain it to be an inherent principle, that without baptism and partaking of the supper of the Lord it is impossible for any man to attain either to the kingdom of God or to salvation and everlasting life? (On Forgiveness of Sins and Baptism, 1:34, in NPNF I, V:28)

[F]rom whatever source it was handed down to the Church – although the authority of the canonical Scriptures cannot be brought forward as speaking expressly in its support. (Letter to Evodius of Uzalis, Epistle 164:6, in NPNF I, I:516)

The custom of Mother Church in baptizing infants [is] certainly not to be scorned, nor is it to be regarded in any way as superfluous, nor is it to be believed that its tradition is anything except Apostolic. (The Literal Interpretation of Genesis, 10,23:39, in William A. Jurgens, editor and translator, The Faith of the Early Fathers, 3 volumes, Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 1970, vol. 3: 86)

St. Augustine refers to “the authority of plenary Councils, which are formed for the whole Christian world . . .” (On Baptism, ii, 3, 4) and “the full illumination and authoritative decision of a plenary Council” (ibid., ii, 4, 5). He states: “He who is the most merciful Lord of faith has both secured the Church in the citadel of authority by most famous ecumenical Councils and the Apostolic sees themselves . . . ” (Ep. 118 [5, 32]; to Deoscorus [written in 410]). I could go on and on with this (having edited The Quotable Augustine also). Once again, White selectively presents one quote, and even it does nothing to prove the point he was trying to make.

For example, Augustine again, “What more shall I teach than that what we read in the Apostles, for holy Scripture speaks as the rule for our doctrine, lest we dare to be wiser than we ought. Therefore, I should not teach you anything else except to expound you the words of the teacher.” The rule of our doctrine it speaks by what? Scripture plus tradition? Scripture plus oral tradition? I don’t believe so.

Yes, that’s what White arbitrarily and unscripturally believes. Augustine, the apostles and fathers, and the Catholic Church do not. I already proved this above, but repetition is a good teacher:

. . . other things which we hold on the authority, not of Scripture, but of tradition, . . . or by plenary Councils,

I believe that this practice [of not rebaptizing heretics and schismatics] comes from apostolic tradition, . . .

. . . had its origin in apostolic tradition, just as there are many things which are observed by the whole Church, . . .

But those reasons which I have here given, I have either gathered from the authority of the church, according to the tradition of our forefathers, or from the testimony of the divine Scriptures, . . . [there’s the “three-legged stool” right there, folks!] (On the Trinity, 4,6:10; NPNF I, III:75)

Protestant Church historian Heiko Oberman summarizes St. Augustine’s rule of faith:

Augustine’s legacy to the middle ages on the question of Scripture and Tradition is a two-fold one. In the first place, he reflects the early Church principle of the coinherence of Scripture and Tradition. While repeatedly asserting the ultimate authority of Scripture, Augustine does not oppose this at all to the authority of the Church Catholic . . . The Church has a practical priority: her authority as expressed in the direction-giving meaning of commovere is an instrumental authority, the door that leads to the fullness of the Word itself.But there is another aspect of Augustine’s thought . . . we find mention of an authoritative extrascriptural oral tradition. While on the one hand the Church “moves” the faithful to discover the authority of Scripture, Scripture on the other hand refers the faithful back to the authority of the Church with regard to a series of issues with which the Apostles did not deal in writing. Augustine refers here to the baptism of heretics . . . (The Harvest of Medieval Theology, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, revised edition of 1967, 370-371)

I am heartened to see that White does nuance his treatment of St. Augustine at least to some extent:

Mr. Matatics then brought up Augustine and I don’t think he understood what I was saying. He turned to me and said, “Are you saying that Augustine never appealed to any tradition outside of Scripture?” and I said, “No, I am not saying that.” Because he most definitely did.

That’s good. But then he immediately forms a dubious theory for why Augustine did that:

Augustine was in a hard spot, as Gerry knows. Augustine was fighting against the Donatists. And who did the Donatists have on their side? Cyprian, the great bishop of Carthage. And when Augustine had to go up against what Cyprian had to say, you bet he referred to all sorts of other things outside of Scripture because he was fighting a losing battle, in some respects, on some of the things that he was saying. I’m not saying that Augustine was perfectly consistent . . .

I highly doubt that this can explain every Augustine appeal to tradition, apostolic succession, councils, or other Church pronouncements as binding authorities.

Basil. Listen to what he says, “The hearers taught in the Scriptures ought to test what is said by teachers and accept that which agrees with the Scriptures but reject that which is foreign.” That is what I believe. We should test anything we are taught by our teachers by what standard? By papal encyclicals? Vatican II? The Council of Trent? No, by the inspired Scriptures.

But St. Basil the Great, too, believes in the “three-legged stool” (including oral traditions) as I documented last time (just go there and search his name, to see it). White leaves himself wide open for decisive rebuttal, with this sort of selective citation and ignoring of other relevant data regarding the one cited. It’s pathetic . . .

I want to read from Augustine again, “You ought to know this and particularly store in your memory that God wanted to lay a firm foundation in the Scriptures against treacherous errors, a foundation against which no one dares to speak who would in any way be considered a Christian.” Listen closely: “For when he offered himself to them to touch,” (he’s talking about the resurrected Lord) “this did not suffice him unless he also confirmed the heart of the believers from the Scriptures. For he foresaw that the time would come when we would not have anything to touch but would have something to read.” Even in the resurrection of the Lord, he confirms their hearts from the Scriptures because he knew that someday they would not have something to touch but would have something to read. My friends, that is what I’m talking about here.

Augustine did not believe in sola Scriptura, as I demonstrated above (and as even White in effect concedes). And what he states above does not contradict Catholic teaching, which he held to. The Bible does have exactly this role to play, along with many others. But it is consistent with the Catholic view; thus, is no disproof of it and no proof of sola Scriptura. But Protestants can always chuck and reject any Church father if and when they are shown to disagree with their novel innovations (supremacy of the individual conscience, private judgment, and sola Scriptura, you see). Luther did. Calvin did.

And I want to again emphasize that Mr. Matatics must demonstrate that this oral tradition, what he is wanting us to accept as being authoritative beyond this, must be God-breathed. He must be able to define what is in it outside of what’s in here and that it is God-breathed. That, truly, is the focus of the debate.

He is under no obligation (nor is any Catholic) to do any such thing. White once again employs this false theory that anything that is authoritative / infallible / binding must be also literally inspired, or part of revelation. That is untrue, and is not an idea or belief that can be found in Holy Scripture. If it can be, then by all means, let him or any other Protestant who believes such an odd thing produce it. He not only keeps repeating this falsehood, but also makes it the “focus of the debate.” This is a very poor performance indeed . . .

Second Rebuttal

Mr. Matatics says that, “Well, the canon–it was done by the councils. Hippo and Carthage. They’re the ones who determined the canon.” That’s interesting. The Muratorian fragment, which dates to nearly 200 years prior to either Hippo or Carthage, listed 97 percent of the canon of the Scripture that I use long before any council began to look at that.

Not quite. According to the chart as determined by Bible scholars, shown in the Wikipedia article, even if we include three “probable” canonical books and two “maybes” we still have 23 out of 27 books, which is 85%. And it also includes in its canon (which fact White conveniently passes over), the Apocalypse of Peter and Wisdom of Solomon. So, yeah: much of the New Testament (especially the Gospels and Pauline epistles) was fairly widely accepted relatively early on.

But there still needed to be an authoritative pronouncement, once and for all. That was provided by the Catholic Church in the 390s (which Church some extreme anti-Catholics think ceased to even be Christian upon the ascension of Emperor Constantine, who ruled from 306-337). It remains true that a complete list of New Testament books only appeared in 367, from St. Athanasius. The “blessed assurance” of that complete list simply wasn’t present before that time. But we stray from your subject matter proper . . .

Chrysostom says, “If anything is said without Scripture the thinking of the hearers limps. But the where the testimony proceeds with divinely given Scripture it confirms both the speech of the preacher and the soul of the hearer.” Elsewhere he says, “Whatever is required for salvation is already completely fulfilled in the Scriptures.”

I have written two papers about St. John Chrysostom’s denial of sola Scriptura and Catholic rule of faith:

St. John Chrysostom (d. 407) vs. Sola Scriptura as the Rule of Faith [8-1-03]

Chrysostom & Irenaeus: Sola Scripturists? (vs. David T. King) [4-20-07]

I won’t bother to cite them (and him) this time. Any reader who wants the documentation can simply follow the links.

If we say you have to look to the Church to authenticate God’s Word, what are we saying about the Church? That is not the church of the New Testament. The Church of the New Testament is the Bride of Christ. She is obedient to the Word of God. She does not authenticate the Word of God. This is not something we should hear coming from a presentation that is supposed to be biblical in nature.

We agree that the Church doesn’t “authenticate” what is intrinsically inspired revelation. But the Church was needed to authoritatively identify the canon and put the differences to rest once and for all. White can talk about “self-authentication” all he wants (and I’ve written about that):

But the fact remains that many good and holy Christians disagreed on the exact formulation of the canon until almost 400 AD. After the Church spoke and definitively declared the canon (which is certainly a profound and seemingly binding authority, isn’t it?), this stopped.

Closing Remarks

First of all, Mr. Matatics has again asserted that Apostolic preaching was inspired. He said it in such a way it sounded like I had denied it. I didn’t. He said that this preaching was passed on to us in a separate way outside of the New Testament, again asserting, and I believe without every having proven it, that what is contained in the Apostolic preaching was different than what was found in the Apostolic writing. Athanasius didn’t believe that. I don’t believe that.

St. Athanasius (like all the Church fathers) also denied sola Scriptura.

Mr. Matatics wants to add to the inspired Scriptures an oral tradition he claims comes from the Apostles.

I still can’t believe that White keeps making this ridiculous claim over and over (I haven’t even cited all of them) . . . And I don’t believe that he could possibly have kept asserting this, these past 27 years. He couldn’t possibly be that dense. Or could he?

Now I’d like, if you still have your Bibles out, for you to turn to Psalm 119:89. I would like to invite you this evening, if you have the opportunity tonight, to read this entire psalm, to read the whole thing and ask yourself if this is the view of the Word of God that you have. Psalm 119:89, “Your word, Oh, Lord, is eternal. It stands firm in the heavens.” . . . The Psalmist knew what the Word of God was. The Psalmist does not cite oral traditions. You won’t find Psalm 120 being in praise of the oral traditions. You find Psalm 119 in praise of the written Word of God.

As far as the terminology “word of God” in the Old Testament, it actually only appears three times in RSV. In 1 Samuel 9:27 and 1 Kings 12:22 it is clearly oral in nature (right from God to a person who proclaims it) and not referring to Scripture. In Proverbs 30:5 it’s not clear that it is written Scripture, either.

“Thy word” appears more times, and mostly in Psalm 119, and many times (2 Sam 7:28; 1 Ki 8:26; 18:36; 2 Chr 6:17 it refers to oral revelation from God to persons: not originally written as Scripture. It’s not absolutely clear that “thy word” in Psalms 119 must refer to written Scripture. I actually think that it probably does, while at the same time noting that the phraseology is not confined to descriptions of only Scripture.

It’s much more clear with regard to the phrase “word of the Lord”: which appears 243 times in the Old Testament in the RSV. These instances are overwhelmingly oral: usually God speaking to prophets and other notable people: Abraham (Gen 15:1), Joshua (Josh 8:27), Samuel (1 Sam 3:21), Nathan (2 Sam 7:4), Gad (2 Sam 24:11), Solomon (1 Ki 6:11), Ahi’jah (1 Ki 14:18), Jehu (1 Ki 16:1), Elijah (1 Ki 18:1), Shemai’ah (2 Chr 11:2), Jeremiah (2 Chr 36:21), Isaiah (Is 38:4), Ezekiel (Ezek 1:3), Hosea (Hos 1:1), Joel (Joel 1:1), Jonah (Jon 1:1), Micah (Mic 1:1), Zephaniah (Zeph 1:1), Haggai (Hag 1:1), Zechariah (Zech 1:1), and Malachi (Mal 1:1).

Note: “And the word of the LORD was rare in those days; there was no frequent vision” (1 Sam 3:1). And the book of Psalms sometimes uses it in an obviously non-Scriptural way: “By the word of the LORD the heavens were made, and all their host by the breath of his mouth” (33:6). Now, with all this “oral communication” going on, clearly, “word of God” / “word of the Lord” / “Thy word” is not confined to written Scripture. And just because one Psalm (119) seems to refer to written Scripture, it doesn’t follow that these terms always referred to inspired writing. Therefore, plainly “oral traditions” existed in Old Testament times, contrary to White’s fanciful imagination.

In fact, mainstream Judaism believed that Moses received oral tradition on Mt. Sinai alongside the written. This was what the Pharisees believed (which Paul more than once called himself). The Sadducees, who were sort of the theological liberals of the time (denying, e.g., the resurrection of the body), denied it. They were the Jewish sola Scripturists. I have an article that discusses many possible Old Testament references to oral tradition or the oral Torah. And I have written about how the Old Testament Jews denied sola Scriptura.

I want you to listen very, very closely to what was said by St. Cyril of Jerusalem, “In regard to the divine and holy mysteries of the faith not the least part may be handed on without the Holy Scriptures. Do not be led astray by winning words and clever arguments. Even to me, who tell you these things, do not give ready belief unless you receive from the Holy Scriptures the proof of the things which I announce. The salvation in which we believe is not proved from clever reasoning but from the Holy Scriptures.” What does that say? What does that say?

I’ve written about St. Cyril’s denial of sola Scriptura three times (White has clearly not listened “very, very closely” enough to Cyril):

Cyril of Jerusalem (d. 386) vs. Sola Scriptura as the Rule of Faith [8-1-03]

Sola Scriptura, Cyril of Jerusalem, Logic, & Anti-Catholics [11-9-17]

I’m not saying that the Church is teaching that oral tradition is superior to Scripture. Please, that’s not what I’m saying. But functionally, that is exactly what happens.

That’s how it looks to an either/or unbiblical thinker who doesn’t fully grasp the Catholic rule of faith. They can only pit one thing against another because they can’t comprehend complementarity. It’s trying to force preconceived notions onto Scripture, which is the dreaded and unworthy practice of eisegesis.

***

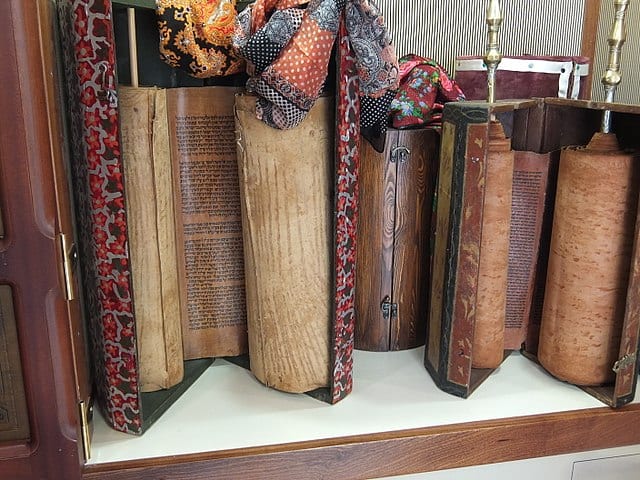

Photo credit: Davidbena (2-25-18): Yemenite Torah scrolls [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license]

***