There is a strain of Protestant thought — most notably the “Landmark” Baptists — which seeks to find a non-Catholic “apostolic succession” all throughout Church history up to the 16th century. In the desperate attempt to claim spiritual and theological predecessors, all sorts of heretical groups are espoused, including the Montanists, Novationists, Donatists, Docetists, Cathari, Albigensians, Waldenses, Hussites, and Wycliffites.

The trouble is that none of these groups fit very well into a Protestant schema. They are either radically non-Christian, even Gnostic (e.g., the Albigensians), or far too Catholic in what they retain (Waldenses, Hussites) to qualify as “proto-Protestant.” Yet that doesn’t stop certain Protestants (especially of the anti-Catholic variety) from latching onto these groups for polemical purposes. “My enemy’s enemy is my ally.”

These claims are only as good as the real knowledge of such groups is scanty and incomplete. On a public bulletin board, I interacted with one such Baptist. His words are indented:

The RCC had previous to the Reformation instituted the bloody and hideous Inquisition, murdering of scores of Waldenses, Albigenses and Cathars.

Do you consider these three groups Christians? If so, why, and what is your documentation?”

Yes, I do, for several reasons:

1) from what little remains of their actual writings, their doctrine is sound, healthy;

2) the character of these groups in reference to Christian virtues is highly commendable, and is admitted even by their adversaries, though they were otherwise notoriously slandered by other Catholics who hated those better than themselves;

3) the real reason for their being persecuted, as also admitted by some inquisitors, is because they rejected RCC traditions, not because they were unorthodox in major biblical doctrines;

4) because our churches descended from theirs and hold to basically the same religious principles, and they also have a succession of churches down to the days of the apostles.

From the Catholic Encyclopedia, copyright © 1913 by the Encyclopedia Press, Inc. Electronic version copyright © 1996 by New Advent, Inc. (N. A. Weber; Transcribed by Anthony A. Killeen):

[my “editorial” comments are interspersed in brackets and in blue]

An heretical sect which appeared in the second half of the twelfth century and, in a considerably modified form, has survived to the present day.

NAME AND ORIGIN

The name was derived from Waldes their founder and occurs also in the variations of Valdesii, Vallenses. Numerous other designations were applied to them . . . Anxious to surround their own history and doctrine with the halo of antiquity, some Waldenses claimed for their churches an Apostolic origin. The first Waldensian congregations, it was maintained, were established by St. Paul who, on his journey to Spain, visited the valleys of Piedmont. The history of these foundations was identified with that of primitive Christendom as long as the Church remained lowly and poor. But in the beginning of the fourth century Pope Sylvester was raised by Constantine, whom he had cured of leprosy, to a position of power and wealth, and the Papacy became unfaithful to its mission. Some Christians, however, remained true to the Faith and practice of the early days, and in the twelfth century a certain Peter appeared who, from the valleys of the Alps, was called “Waldes”. He was not the founder of a new sect, but a missionary among these faithful observers of the genuine Christian law, and he gained numerous adherents. This account was, indeed, far from being universally accredited among the Waldenses; many of them, however, for a considerable period accepted as founded on fact the assertion that they originated in the time of Constantine. Others among them considered Claudius of Turin (died 840), Berengarius of Tours (died 1088), or other such men who had preceded Waldes, the first representatives of the sect.

The claim of its Constantinian origin was for a long time credulously accepted as valid by Protestant historians. In the nineteenth century, however, it became evident to critics that the Waldensian documents had been tampered with. As a result the pretentious claims of the Waldenses to high antiquity were relegated to the realm of fable . . .

DOCTRINE

The organization of the Waldenses was a reaction against the great splendour and outward display existing in the medieval Church; it was a practical protest against the worldly lives of some contemporary churchmen. Amid such ecclesiastical conditions the Waldenses made the profession of extreme poverty a prominent feature in their own lives, and emphasized by their practice the need for the much neglected task of preaching. As they were mainly recruited among circles not only devoid of theological training, but also lacking generally in education, it was inevitable that error should mar their teaching, and just as inevitable that, in consequence, ecclesiastical authorities should put a stop to their evangelistic work. Among the doctrinal errors which they propagated was the denial of purgatory, and of indulgences and prayers for the dead. They denounced all lying as a grievous sin, refused to take oaths and considered the shedding of human blood unlawful. They consequently condemned war and the infliction of the death penalty. Some points in this teaching so strikingly resemble the Cathari that the borrowing of the Waldenses from them may be looked upon as a certainty. Both sects also had a similar organization, being divided into two classes, the Perfect (perfecti) and the Friends or Believers (amici or credentes).

Among the Waldenses the perfect, bound by the vow of poverty, wandered about from place to place preaching. Such an itinerant life was ill-suited for the married state, and to the profession of poverty they added the vow of chastity. Married persons who desired to join them were permitted to dissolve their union without the consent of their consort. Orderly government was secured by the additional vow of obedience to superiors. The perfect were not allowed to perform manual labour, but were to depend for their subsistence on the members of the sect known as the friends. These continued to live in the world, married, owned property, and engaged in secular pursuits. Their generosity and alms were to provide for the material needs of the perfect.

The friends remained in union with the Catholic Church and continued to receive its sacraments with the exception of penance, for which they sought out, whenever possible, one of their own ministers.

[I thought they were opposed to the Catholic Church? Baptists “in union with” Catholics? Hmmmmmm . . . ]

The name Waldenses was at first exclusively reserved to the perfect; but in the course of the thirteenth century the friends were also included in the designation.

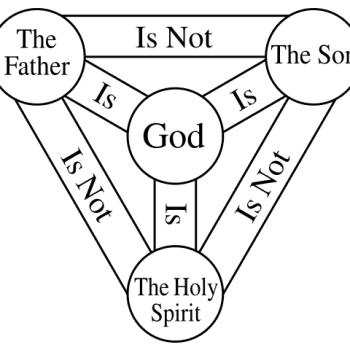

The perfect were divided into the three classes of bishops, priests, and deacons. The bishop, called “major” or “majoralis”, preached and administered the sacraments of penance, Eucharist, and order.

[Priests? Bishops? Sacraments? Penance? Sacrament of the Eucharist? Is this Baptist?]

The celebration of the Eucharist, frequent perhaps in the early period, soon took place only on Holy Thursday. The priest preached and enjoyed limited faculties for the hearing of confessions . . . .

[What???!!!! “Confessions?!!!” Don’t they go straight to God, or to an offending party?]

Holding that the validity of the sacraments depends on the worthiness of the minister

[Since when do Baptists have sacraments? Why would the validity of the minister be a question at all, since sacraments are supposedly unbiblical and instruments of “works-salvation” to begin with?]

and viewing the Catholic Church as the community of Satan, they rejected its entire organization in so far as it was not based on the Scriptures.

[Ah! Now this sounds more like an anti-Catholic type of Baptist — too bad those other thorny “Catholic” details have to be worked out . . . ]

In regard to the reception of the sacraments, their practice was less radical than their theory. Although they looked upon the Catholic priests as unworthy ministers, they not infrequently received communion at their hands and justified this course on the grounds that God nullifies the defect of the minister and directly grants his grace to the worthy recipient.

[How many Baptists do this today, I wonder?]

The present Waldensian Church may be regarded as a Protestant sect of the Calvinistic type . . .

[Indeed, but that is post-“Reformation.” That no more proves that the earlier Waldenses were “Protestants,” let alone Baptists, than does the 16th-century conversion of the Scandinavian countries to Lutheranism or Scotland to Presbyterianism prove that the religion earlier in those regions was not Catholic. This is anachronistic special pleading of the worst sort.

Protestants who cite the Waldenses as forerunners would do better to admit that they could care less about Church history — that would be more consistent. The fact remains that Waldenses (and far more so, Albigensians) were not Baptists. That much is clear from the above information. They were not Catholics, either (or if so, only in individual cases, and imperfectly), but we are not claiming a lineage from them. Certain anti-Catholic Protestants — particularly Landmark Baptists — are]

***

(originally 6-7-98)

Photo credit: In the Waldensian Valleys, Italy. @1895: View from the [town of] Torre of the Valley (Keystone View Company Studios. Meadville, PA © Underwood & Underwood) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***