The Calvinist’s words will be in blue.

*****

Thanks for writing and for deciding to link to my page. I like your website — it is very classy, visually appealing and well-presented. You asked:

On your page, you say that justification is not part of the gospel. But wasn’t the problem that Paul was addressing to the Galatian church justification by faith plus works? And since in 1:8-9 he condemns those who were teaching this, calling it a “contrary gospel,” didn’t Paul consider justification part of the gospel?

This is a fair question, and is well thought out. And the answer involves a recognition of something common in Scripture: multiple meanings of words. In my paper What is the Gospel?, I took the position that the gospel, strictly defined, is the death, burial and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and what that meant in terms of freely granted salvation of sinners. The Good News is that Jesus died for us, not “faith alone,” to put it bluntly.

And this was derived from the explicit definitional testimony of Scripture itself. Within that wide parameter, there are different theological notions of justification and sanctification, as you well know. But I maintain that all the three major traditions of Christianity concur wholeheartedly in their adherence to the gospel so defined.

As to Galatians, that gets into what Paul means by “works” and “works of the law,” etc., and their relationship to faith. I have several links to papers by Catholic apologist Jimmy Akin (formerly Reformed) along those lines, on my salvation and justification page, but I include here an excerpt by my friend Al Kresta, my former evangelical pastor, and now also a Catholic:

Paul’s arguments against works of the law are not fundamentally arguments against human participation in or human cooperation with the saving purposes of God but arguments against Judaistic pride that sought to define membership in the covenant community by reference to Jewish marks of identity, such as circumcision, Sabbath-keeping, etc. and not fundamentally faith in Jesus as Messiah.

Contrary to the pronouncements of popular preachers, first century Judaism did not believe in salvation by works. They believed that they were God’s elect people by grace; lawkeeping was their response to God’s grace. Salvation was understood to be granted by God’s electing grace, not according to a righteousness based on merit-earning works. But most Protestant scholars since Luther have read Paul as saying that Judaism misunderstood the gracious nature of God’s covenant with Moses and perverted it into a system of attaining righteousness by works.

Wrong! Luther’s experience was not Paul’s. New Testament scholars, for the most part, now understand works of law not as synonymous with human effort but as the activities by which the Jews maintained their distinct status from the Gentiles . . .

For Paul, these boundary-defining features distinguished Israel in the flesh (Romans 2:28) and encouraged Jews to boast in their national identity (Romans 3:27-29; Galatians 2:16; 6:13). They were obstructing the extension of God’s grace to the nations through Christ. In so doing, they were undermining their very purpose of existence: all the nations were supposed to be blessed by the offspring of Abraham (Genesis 12:3; Deuteronomy 4:6; Isaiah 66:20). So when Paul says of the Jews that “they sought to establish their own righteousness” (Romans 10:3) he doesn’t mean that they were trying to earn their salvation through human exertion but that they arrogated to themselves the authority to set the conditions by which believing Gentiles could be regarded as full members in the new covenant community. They rejected the authoritative apostolic teaching that the Gentiles and Jews constituted one body (Acts 15:1,24; Galatians 1:7; 2:12; 5:10; Ephesians 2-3:13) and they sought to thwart God’s inclusion of the Gentiles by insisting that Gentiles first become Jews through circumcision, etc., rather than through faith in Jesus, who is the ‘aim’ or ‘end’ of the law (Philippians 3:2; Galatians 5:6; 6:15; 1 Corinthians 7:19; Romans 10:4). They were retrogressive . . . (From unpublished lecture notes entitled Some Further Thoughts on Justification by Faith Through Grace (1993); used by express permission of the author; later cited in my book, A Biblical Defense of Catholicism)

This sounds a lot like salvation by grace alone, through faith alone (since it is not a righteousness based on merit-earning works).

It is grace alone, since grace is the origin and first cause of all good works. That is not in dispute. It is not faith alone, because – as stated above – there is human cooperation and participation with God-originated grace, and faith and works go hand-in-hand — two sides of the same coin (cf. James). Since Calvin and Luther summarily denied human free will, one would expect “cooperation” to be impossible in classic Reformed theology. But is this biblical? I say no . . .

In Romans 3:20 Paul writes “because by the works of the law no flesh will be justified in His sight; for through the Law comes knowledge of sin.” I don’t think that it can be maintained that in this verse Paul is only talking about Jewish “marks of identity.” For verses 19-20 are given as the logical conclusion of verses 9-12. Since in verses 9-18 Paul is very clearly declaring that we all fail to keep the moral law of God, then verses 19-20 must also be referring to the moral law of God.

Therefore, verse 20 says that nobody will be justified through obeying the moral commands of God–that is, by living a good life. Instead, the function of the law is to make known our sin. And since the law cannot be the means of justification, we must seek justification through other means–faith (this is verses 21-22). Do you agree with this? If so, where is our disagreement? If you don’t agree, where is my mistake in interpreting these passages?

Yes, we do agree on this particular point. What I quoted was a general commentary on Paul’s use of the term works of the law, not an exhaustive one. This passage indeed refers to the Moral Law, by which no man can be saved, just as Paul says. No disagreement exists on this point. Both my and your beef here would be with Pelagians, not each other. Again, the real difference arises over human cooperation, the progressive and infused nature of justification, and the notion and nature of “merit.”

Accordingly, Trent speaks of our “freely assenting to and cooperating with that said grace” while adding, “yet he is not able, by his own free-will, without the grace of God, to move himself unto justice in His sight.” (Decree on Justification: Chapter V).

And:

None of these things which precede justification – whether faith or works – merit the grace itself of justification. For, if it be a grace, it is not now by works; otherwise, as the same Apostle says, grace is no more grace. (Chapter VIII)

And:

If anyone says that man may be justified before God by his own works, whether done through the teaching of human nature or that of the law, without the grace of God through Jesus Christ; let him be anathema. (Canon I on Justification)

I have steadily maintained that the crux of the dispute vis-a-vis justification and salvation is free will. If we are truly free, then we can cooperate with the grace God gives us (and then the notion of “merit” enters in). Luther, knowing this, thought The Bondage of the Will his most important work, and Calvin made it a cornerstone of his theological system.

A strict sola fide follows of necessity once one denies free will. But many Protestants — of course — differ with classical Reformed theology. I have argued with Calvinist apologists that Arminians such as C. S. Lewis, Philip Melanchthon, and John Wesley, should equally be the target of their scathing critiques of “Pelagianism,” “religion of works,” etc., if they must go after Catholics on this score. But as of yet, none has ever conceded (or grasped?) that point!

So, in conclusion, we maintain that the point of the Epistle to the Galatians is not a treatise on justification (i.e., as defined by many evangelical Protestants: sola fide), but the above considerations. Even if it were about faith + works as a means of salvation, this would not have relevance to Catholic teaching, but rather, Pelagianism and Semi-Pelagianism, both of which were condemned by the Catholic Church at the 2nd Council of Orange (529) and reiterated by Trent.

From that perspective, I say that the real and crucial dividing line over the gospel and salvation lies between Nicene, Chalcedonian Christians (Catholics, Protestant, and Orthodox) and Pelagians (including Semi-Pelagians). All of those Christians accept the absolutely gratuitous and free nature of grace and salvation. Catholicism — rightly understood — does not teach a “salvation by works” theology, for that is the Pelagian heresy. In other words, the inter-Christian squabbles are about the place of free will and man’s cooperation and their relationship to God’s sovereignty and necessary initiation of all grace and good works, not over whether or not God’s grace is always primary and initiatory.

In Galatians, Paul uses gospel in a wider sense, that of the entire deposit of faith or Christian tradition or word of God. I have argued that these are used interchangeably in Scripture, and are essentially synonymous, as evidenced by the following comparison:

1 Corinthians 11:2 . . . maintain the traditions . . . even as I have delivered them to you.

2 Thessalonians 2:15 . . . hold to the traditions . . . taught . . . by word of mouth or by letter.

2 Thessalonians 3:6 . . . the tradition that you received from us.

1 Corinthians 15:1 . . . the gospel, which you received . . .

Galatians 1:9 . . . the gospel . . . which you received.

1 Thessalonians 2:9 . . . we preached to you the gospel of God.

Acts 8:14 . . . Samaria had received the word of God . . .

1 Thessalonians 2:13 . . . you received the word of God, which you heard from us, . . .

2 Peter 2:21 . . . the holy commandment delivered to them.

Jude 3 . . . the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints.

So there you have it! This necessarily had to get into many related issues. In any event, if the gospel is defined (falsely, I think) as simply the Reformed notion of sola fide or TULIP, then Calvinists and Baptists will have to define Methodists (including John Wesley), Lutherans (including Melanchthon and Bonhoeffer and Kierkegaard), Anglicans (including C.S. Lewis), and many charismatics and independents out of the Christian faith as well.

The trouble is, I’ve rarely seen “non-ecumenical” evangelicals act consistently and start to challenge their Arminian brethren. Rather, they want to define us Catholics out of the faith, and “pick on” us exclusively, while not even understanding our nuanced soteriology, nor realizing the inconsistency of their position vis-a-vis Arminian Protestants (not to mention the Bible itself).

Again, neither Catholics nor Arminians are Pelagians. Anyone who states otherwise is quite ignorant of Tridentine theology and the definition and history of Pelagianism (and even Semi-Pelagianism). There are differences over free will, but I fail to see how that renders a particular soteriology (whether Catholic or Arminian/Wesleyan) “non-Christian.” Catholics merely deny that faith and works are unalterably opposed in the nature of things. We regard it as “both/and” rather than “either/or.”

***

(originally 1997)

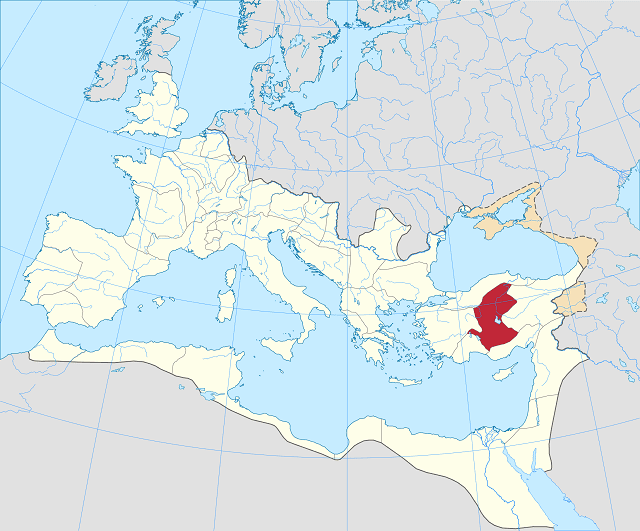

Photo credit: Shadowxfox (11-17-15). Galatia province in the Roman Empire (125). Extracted from File:Roman Empire 125 political map.svg [Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license]

***