***

Protestant historian Roland H. Bainton (Here I Stand) is obviously very fond of Martin Luther (biographers generally are fond of their subjects). But he (like all fair and thorough historians) is not averse to reporting facts that reflect negatively on Luther. The fact that an admirer does so (and a reputable scholar to boot) gives the report more credibility and believability, since the possibility of bias is far less. A generally “positive” or favorable witness saying something negative, and a generally hostile witness expressing something positive, are both examples of more persuasive argumentation. I use these sorts of witnesses all the time in my apologetics, because they provide for forceful, less questionable presentation of one’s case.

Everyone understands that Bainton will have a more favorable view of Luther overall, but that doesn’t negate a scenario where he may agree with me on particulars.

People (mostly Protestants) may be out there thinking, “yeah, that Catholic Armstrong guy has such an ax to grind against Luther that we can’t trust what he asserts in his papers. He is untrustworthy.” I’ve been accused of “hating” Luther, of holding that he is a fundamentally immoral character or “bad man”, etc. — all sorts of nonsense. Again, these potshots are easy to say; much harder to prove from direct analysis and concrete example.

[T]he conflicts and the labors of the dramatic years had impaired his health and made him prematurely an irascible old man, petulant, peevish, unrestrained, and at times positively coarse. This is no doubt another reason why biographers prefer to be brief in dealing with this period. There are several incidents over which one would rather draw the veil . . . (Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther, New York: New American Library, 1950, 292)

I am concerned with facts; namely: whether the older Luther had these negative characteristics or not. No more, no less. Bainton (the “positive” or “partisan” biographer) clearly agrees with me. In my research I was not dealing with this proposition:

x. Whether Luther partook of the characteristic of “greatness” and had a huge “impact” (or whether the same should be “dismissed”).

But rather:

y. Whether the older Luther was (as Bainton put it) “an irascible old man, petulant, peevish, unrestrained, and at times positively coarse.”

Note that proposition y does not intrinsically nullify x. In fact, it has nothing directly to do with it. The two considerations are entirely distinct. I could state, for example:

a. George Washington was a great man who had considerable impact on American culture and history and government.

At the same time, I could assert the following, which does not necessarily contradict the first statement:

b. George Washington had a huge problem with his temper, was often a nominal churchgoer, and held slaves.

Now, when I assert b (all of which is abundantly documented by historians, and quite unarguable), does this mean that I am somehow overlooking or denying a? Of course not. Not at all. I wholeheartedly believe that George Washington was a very great man, to be highly honored and revered as an American Founding father. We may say that there was some contradiction in the person Washington, just as there is in all of us, due to original sin and actual sin in our lives. But it doesn’t follow that we must deny their greatness. The analogy to Luther is exactly apt. Obviously, as a Catholic, I don’t have the favorable opinion of Luther that any Protestant would have (and that I used to have myself), but my opinion is not nearly as negative as many critics of mine in this regard seem to think (if only they could figure that out).

The facts of the matter of the nature of the later Luther’s temperament, psychological shortcomings, etc., are well documented, and I could easily produce much more along those lines from my own library alone. That was my subject. Bainton paints a rosier “big picture,” and sets the negatives in a larger context of Luther’s overall life and accomplishment. One would expect a partisan biographer to do this. All the more significance, then, should be given to the fact that Bainton basically agreed with me in my criticisms. They came from a man who thinks very highly of Luther.

I could just as easily maintain that Bainton’s accompanying qualifications are just as biased as my pointing out the “negatives,” because they might be construed as a sort of “damage control” or “Luther PR.” I don’t see how one thing is any worse than the other. The partisan of Luther offers one interpretation of the same set of facts under consideration, and the critic offers another, and a different emphasis. All this shows is that all parties have bias. But it does not show that I have an undue bias.

I am simply criticizing an important historical figure, because Protestants have been lionizing him lo these many years. It is “setting the record straight.” All I am doing is showing all the facts about Luther, not just solely or primarily certain, highly-selective ones that are routinely emphasized by Protestants. I fail to see what is wrong with that. Protestants may not like it (most people feel very uncomfortable about any criticism of their great heroes) but that doesn’t make it wrong.

I don’t see how it is somehow wrong for me, as a critic of Luther, to point out some uncomfortable facts that every Protestant biographer of any repute also points out. To go after me for this simply because I don’t take a positive view overall of Luther’s impact (as a Catholic) is no more fair than it would be to go after Protestant biographers who back me up in every particular I bring to the table. If I am wrong, so are they, if we understand that the topic at hand is whether the old Luther had certain faults, as opposed to: “everyone should have an equal estimate of how great and wonderful Luther was.” People will differ on the latter, just as they do concerning any great historical figure.

You shouldn’t expect a Republican to write glowing praise of Bill Clinton or LBJ or FDR, or a Democrat to go on endlessly about the greatness and historical impact of Ronald Reagan or the two Bush’s. Likewise, an orthodox Catholic can only go so far in praise of Luther. It’s almost as if to simply take a conventional Catholic view of Luther is to immediately be unfair and unduly biased, by that fact alone. This is unreasonable and unacceptable.

But back to the actual factual matter (supposedly) at hand: Luther’s “irascible nature” in his old age. Is this some controversial thing? Is it (if granted) insignificant? I say “no” to both questions. All of this is well documented and not even controversial. I have done nothing wrong in this regard; I haven’t misrepresented Luther, and I have done nothing that scores of Protestant historians have not also done. Here are “supporting” opinions of two more Protestant historians on the “later Luther”:

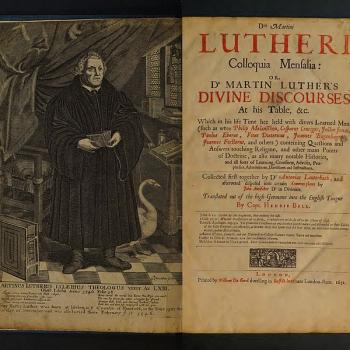

1) Luther’s Last Battles: Politics and Polemics, 1531-1546, by Mark U. Edwards, Jr. (Ithaca, New York and London: Cornell University Press, 1983, 150-155).

2) Heiko A. Oberman, Luther: Man Between God and the Devil, translated by Eileen Walliser-Schwarzbart, New York: Doubleday Image, 1992, 290-292).

If anything, Edwards and Oberman take an even more negative view of Luther in this regard than I do myself.

In fact, even fellow Protestant “Reformers” held an opinion of Luther far lower than my own. For example, Heinrich Bullinger:

Everyone must be astonished at the harsh and presumptuous spirit of the man . . . The opinion of posterity will be that Luther was . . . a man ruled by criminal passions. Luther’s rude hostility might be allowed to pass would he but leave intact respect for Holy Scripture . . . What has already taken place leads us to apprehend that this man will eventually bring great misfortune upon the Church. (Letter to Martin Bucer, December 8, 1543; in Hartmann Grisar, Luther, translated by E. M. Lamond, edited by Luigi Cappadelta, 6 volumes, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., 1917; V, 409 and III, 417)

Or how about Huldreich Zwingli?:

May I be lost if he does not surpass Faber in foolishness, Eck in impurity, Cochlaeus in impudence, and to sum it up shortly, all the vicious in vice. (Letter to Conrad Sam of Ulm, August 30, 1528; in Grisar, III, 277)

If that weren’t enough, what about John Calvin himself? Writing to Luther’s right hand man Philip Melanchthon, Calvin stated:

Your Pericles [Luther] allows himself to be carried beyond all due bounds with his love of thunder . . . But, you will say, his disposition is vehement, and his impetuosity is ungovernable; — as if that very vehemence did not break forth with all the greater violence when all shew themselves alike indulgent to him, and allow him to have his way, unquestioned. If this specimen of overbearing tyranny has sprung forth already as the early blossom in the springtide of a reviving Church, what must we expect in a short time, when affairs have fallen into a far worse condition? (28 June 1545; Letter CXXXVI in Selected Works of John Calvin: Tracts and Letters, edited by Henry Beveridge and Jules Bonnet, Volume 4: Letters, Part 1: 1528-1545, translated by David Constable, Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1858; reprinted by Baker Book House [Grand Rapids, Michigan], 1983, 466-467)

He was even more critical in a letter to Bullinger (the “Reformers” had a knack of griping about each other in such letters):

I hear that Luther has at length broken forth in fierce invective, not so much against you as against the whole of us [referring to Luther’s Short Confession Concerning the Supper] . . . But while he is endued with rare and excellent virtues, he labours at the same time under serious faults. Would that he had rather studied to curb this restless, uneasy temperament which is so apt to boil over in every direction. I wish, moreover, that he had always bestowed the fruits of that vehemence of natural temperament upon the enemies of the truth, and that he had not flashed his lightning sometimes also upon the servants of the Lord. Would that he had been more observant and careful in the acknowledgment of his own vices. Flatterers have done him much mischief, since he is naturally too prone to be over-indulgent to himself. It is our part, however, so to reprove whatsoever evil qualities may beset him, as that we may make some allowance for him at the same time on the score of these remarkable endowments with which he has been gifted. (25 November 1544; Letter CXXII, ibid., 432-433)

So if even John Calvin can severely criticize Luther in this fashion, while not denying that he also has good qualities, why can’t a Catholic apologist like myself do so, and why can’t I cite Bainton along the same lines without denying that Bainton likes Luther and says “good stuff” about him too? Is it simply because I am a Catholic? If I am wrong, are not Calvin, Bullinger, and Zwingli also, since they “attacked” Luther’s character (and even more severely than I did, in some instances)? And if they aren’t wrong, why am I considered to be? Just a few of the many questions my anti-Catholic critics ought to answer when they offer up these erroneous and thoroughly wrongheaded critiques . . . . .

As to Luther’s commissioning of vulgar art to mock Catholics, Roland Bainton describes the “art” as “outrageously vulgar . . . in all of this he was utterly unrestrained.” Bainton’s personal opinion regarding why Luther commissioned this “art”, and its precipitating causes has nothing to do (logically) with either the question of whether the art was in fact vulgar and objectionable, nor even anything directly to do with his own opinion of the art itself (regardless of how it originated).

What caused the outburst is secondary to the question of whether it was indeed vulgar or not. To offer “mitigating circumstances” might help us to better understand why Luther did this, but it has no bearing on the objective morality of the action. To give an analogy: say that a man had a bad day at work, got a ticket on the way home, had a flat tire, and fell into a mud puddle with his nicest suit on. He then proceeded to storm into the house and strangle his cat. Now, is the strangling of the cat justified by what came before? Of course not. The ethics and morality of that action exist apart from the factors of a “bad day” which preceded it. This is Christian ethics. We are not relativists or advocates of situation ethics.

Likewise, the art by Cranach which Luther commissioned and was directly involved in is either vulgar or it is not. Most people who have written about it that I have ever come across (Protestant or Catholic) have readily agreed that it was objectionable and in very poor taste. Bainton minces no words. He describes it as “outrageously vulgar” and “utterly unrestrained” and Luther’s general attitude as “more vituperative” and “more bitter” and an example of “hurling vitriol.”

Note that Bainton qualifies his opinion: “His railing against the pope became perhaps the more vituperative . . .” He doesn’t know for sure; he is merely speculating. Bainton thinks that Luther “compensated” for his frustration over the lack of a public hearing by “hurling vitriol.” Well, this is an interesting theory, and possibly true (it’s plausible) , but it is doubtful that it could be proven, short of a direct confirmation from Luther himself.

In any event, I don’t see how any of this relative minutiae demonstrates that Bainton approved of the art, and that was, again, my subject matter (whether this art was objectionable). He uses very definite language of disapproval. “Outrageously vulgar” and “utterly unrestrained”? That sure sounds to me like Roland Bainton was opposed to this “art” and didn’t think much of it. So he gives some possible mitigating factors? So what? It doesn’t follow that he therefore approves of the art itself. Every indication is that he did not. And insofar as he took a negative opinion of it, he agreed with my assessment, which is why I cited him (particularly and precisely because he is such a well-known Luther biographer).

The whole charge of one critic of mine, was that Bainton was “sympathetic” and did not “come down hard” on Luther, whereas I supposedly was not, and did, and cited Bainton incorrectly because I left out this aspect. But our tasks were different in the first place. Bainton’s task was to produce a biography from a Protestant perspective. His work might be called “Protestant semi-hagiography.” My project, on the other hand (as explained very carefully in several places) was to highlight some of the unsavory aspects of Luther’s life that are less well-known.

I urged readers to read Protestant biographies too, to get a fuller picture (to read both sides), but my purpose was not conventional biography. Nor was it “digging up dirt” or a “hit piece,” as many of my critics falsely assume in their incorrect understanding of my motivations and goals in my writings about Luther. It was simply to bring out lesser-known, more controversial aspects of Luther’s life and teachings.

I cited above the book, Luther’s Last Battles: Politics and Polemics, 1531-1546, by Protestant scholar Mark U. Edwards, Jr. He described Luther’s work, Against the Papacy at Rome, Founded by the Devil (March 1545) , as “Without question . . . the most intentionally violent and vulgar writing to come from Luther’s pen” (p. 163).

Here are the texts of the eight commissioned “cartoons”: their titles, and Luther’s silly accompanying verses (from Edwards, pp. 190-198; originally appearing in vol. 54 of Luther’s Works, Weimar edition, pp. 346-373; along with my descriptions — having seen the pictures):

1. The Kingdom of Satan and the Pope. 2 Thessalonians 2

In the name of all devils the pope sits here, now revealed as the true antichrist as proclaimed in Scripture.

[the pope is seated in the “jaws of hell,” surrounded by demons]

2. Just Reward for the Most Satanic Pope and His Cardinals

If the pope and cardinals were to receive temporal punishment on earth, their blasphemous tongues would deserve what is rightly depicted here.

3. The Pope, God of the World, is Worshiped

The pope has treated the kingdom of Christ just as his crown is here being treated. If you have doubts about it, the [holy] spirit says [Rev 18] pour it in with good cheer, God Himself commands it.

4. Birth and Origin of the Pope

Here is born the antichrist. Megaera is his wetnurse, Allecto his nursemaid, [and] Tisiphone who walks him.

5. The Monster of Rome, Found Dead in the Tiber, 1496

What God Himself thinks of the papacy is shown here by this horrible picture, which should horrify all who would take it to heart.

[A hybrid naked, demon-like female creature (standing), half lizard and half donkey, with two demon-heads comprising a “tail”]

6. The Pope Offers a Council in Germany / Pope, Doctor of Theology, and Master of Faith (double illustration)

Sow, you must allow yourself to be ridden, and well spurred on both sides. You wish to have a council: for that here is my turd.

[The pope rides on a pig, holding excrement in his hand]

Only the pope can interpret the scripture and sweep away error, just as a donkey can pipe and sound the right notes.

[just as the verse describes]

7. The Pope Thanks the Emperor for His Immense Benefits

The emperor has done much good for the pope and checked evil. For that the pope thanked him, as this picture truly shows you.

[The pope is an executioner, about to behead the kneeling and praying emperor with a huge sword]

8. Kissing the Pope’s Feet

Don’t frighten us, Pope, with your ban, and don’t be such a furious man. Otherwise we shall turn away and show you our rears.

[The pope is seated on a throne, with tiara, holding a decree, with two attending cardinals. Two disrespectful men — Lutherans no doubt — are turning away from him, looking back, sticking out their tongues. Further description would be too vulgar; knowing Luther’s “young teenagers in the locker room” mentality by now, the reader can easily imagine the rest, extrapolating from the text]

The Introduction for this hideous tract, in Luther’s Works, the 55-volume American edition, describes it as “the most bitter of Luther’s polemic writings” (LW, 41, 259-290). As is to be expected, some justification is also given for this tirade:

Luther seemed to know that he had not much time left-death would come soon, but not before the fiercest enemy of his cause, the papacy, received his scorn and violent condemnation. This polemical tract, like Against Hanswurst, reveals the faith and wrath of the old Luther. Yet one should not forget that his tracts usually originated as replies against equally abusive and violent attacks. “Dogmatic, superstitious, intolerant, overbearing, and violent as he was, he yet had that inscrutable prerogative of genius of transforming what he touched into new values.” [footnote: Quoted in Schwiebert, Luther and His Times, p. 747, from Preserved Smith, The Age of the Reformation.]

I happen to have one of two paperback volumes of Preserved Smith’s book, mentioned above. Smith is quite sympathetic and complimentary to Luther (I have no problem with that at all), but is also very frank about the man’s faults, on the same page where his words above appear:

During his later years Luther’s polemic never flagged. His last book, Against the Papacy of Rome, founded by the Devil, surpassed Cicero and the humanists and all that had ever been known in the virulence of its invective . . . Of course such lack of restraint largely defeated its own ends. The Swiss Reformer Bullinger called it “amazingly violent,” and a book than which he “had never read anything more savage or imprudent.” Our judgment of it must be tempered by the consideration that Luther suffered in his last years from a nervous malady and from other painful diseases, due partly to overwork and lack of exercise, partly to the quantities of alcohol he imbibed, though he never became intoxicated. (Reformation in Europe, Book I of a two-volume edition of The Age of Reformation, New York: Collier Books, 1962; originally 1920, 102)

Again, Smith as a fair, careful biographer, tells the truth about the nature of the work and also includes factors in Luther’s life which might account for its severity and extremity. This is reality: human beings are radical mixtures of good and evil. Would that most movies could present characters in the multiform complexity typical of good biographies and novels. That’s all fine and good. But the fact remains that this art and the work it accompanies are vulgar and outrageous, as well as ridiculously, grotesquely slanderous of the Catholic Church.

I don’t see that Catholic descriptions of these pathetic cartoons or the similar tract with which they were associated surpass by far, if at all, Protestant descriptions already observed above in Bainton, Edwards, and Smith. Catholic Luther biographer Hartmann Grisar, for example describes them as “crude defilement,” “vulgar beyond all description,” and “repulsive.” He continues:

The entire collection has become extremely rare, owing probably to the outraged sensibilities of those who were offended by them. In recent times, these cartoons have been re-submitted to the public in the interests of history, but not by partisans of Luther.

Luther’s active participation in the “Illustrations of the Papacy” has been placed beyond question by recent research . . . [he] contribut[ed] the ideas and the crude verses that accompanied the cartoons. His name is attached to the illustrations of the series, as well as to the cartoon of the pope-devil. The drawings themselves were without exception the product of his confidant, Lucas Cranach, . . .

Hence, it is historically untenable if Protestant authors hold Cranach solely responsible for the disgraceful cartoons of the papacy and ascribe only the text to Luther. These illustrations are his spiritual property in the fullest sense of the word, and Luther himself described them as his last will and testament to the German nation. (Martin Luther: His Life and Work, translated from the second German edition by Frank J. Eble, edited by Arthur Preuss, Westminster, Maryland: The Newman Press, 1960; originally 1930, 547-548)

Bainton described the “art” as “outrageously vulgar” and “utterly restrained.” I don’t see much difference.

In 1530 Luther advanced the view that two offences should be penalized even with death, namely sedition and blasphemy . . . Luther construed mere abstention from public office and military service as sedition and a rejection of an article of the Apostles’ Creed as blasphemy. In a memorandum of 1531, composed by Melanchthon and signed by Luther, a rejection of the ministerial office was described as insufferable blasphemy, and the disintegration of the Church as sedition against the ecclesiastical order. In a memorandum of 1536, again composed by Melanchthon and signed by Luther, the distinction between the peaceful and the revolutionary Anabaptists was obliterated. (Roland Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther, New York: Mentor, 1950, 295)

I repeatedly have written about how Luther had a tolerant position early on, adopted a more persecuting position around 1530, then returned to his earlier position later on. My paper on the Peasants’ Revolt is filled with several dozen “peaceful” remarks of Luther from 1521-1525. In my first paper about Martin Luther, written in 1991 (since removed from my site), I cited historian Will Durant, stating exactly all these things. I knew this about Luther in 1984, when I first read Bainton’s book.

Bainton talks about both whether Luther advocated the death penalty and why he did. I was always writing about the “whether” aspect, because I am concerned about Protestants who are unaware of this, or who flat-out deny it. Why he did so, or how tolerant he was compared to others, are interesting and important questions, but different ones from my subject-matter. Therefore, to not cite Bainton in that regard is not incorrect or objectionable, because it is a distinct, separate question, beyond my purpose and purview. If I am seeking to establish that Luther held these views, I can cite Bainton in support of my view. I don’t have to go to the next step of analysis.

My papers have demonstrated that Luther held a position of capital punishment for what he called “sedition,” not the rationale for why he did so. He thought belief in adult baptism was so subversive of society that it was seditious as well. I would contend that the criteria for death were at bottom theological and doctrinal.

The wife of a Lutheran pastor (LCMS) whom I encountered on the Internet flat-out denied that Luther ever advocated the death penalty for heresy (or sedition, but applied to these groups with a different theology). She went and wrote to a Lutheran scholar, and he asserted the same thing. I simply referred them to Bainton, and wondered aloud how it was that two highly-placed Lutherans did not know something that I learned in 1984 when I read Bainton’s book??!! But of course the reason is because of the success of the Protestant mythology of origins, which causes many people to believe these silly falsehoods and a bunch of lies about the Catholic Church of that period and today.

Now, the point is, if someone is denying the very facts of the matter, then that is how one must respond. One doesn’t necessarily have to get into the “why’s” because the fundamental dispute has to be dealt with first. Some atheists deny that Jesus existed. So with them, you have to deal with that before going onto analyses of the Sermon on the Mount, etc. All that is irrelevant if the person thinks you are dealing with a fictional character and not a real historical person. Likewise, if someone denies that Luther advocated the death penalty, it is pointless to talk about why he did so, and how “lenient” he was compared to others, because the very fact which is the subject of the speculation of “why” and “how?” is in dispute. First things first . . .

In 1536, the distinction between peaceful and revolutionary Anabaptists was obliterated, as noted by Bainton. In other words, this was an increase in violence against them, not a decrease, because the peaceful Anabaptists were regarded in the same way as the revolutionary ones: as seditious and thus worthy of death. Bainton stated that the change back to the earlier position (regarding a distinction of types of Anabaptists) came in 1540, and then Durant informed us that right before he died, Luther returned to his pre-1525 position of relative tolerance and freedom of religion.

I noted all this in my earliest papers about Luther. The whole insinuation that I somehow have done otherwise is a total bum rap, without a shred of truth. Sure, I have emphases in accord with my clearly-stated purpose, but I’ve never hidden any of this stuff that some of my critics have emphasized.

Nor is there any rule written down which states that “Dave Armstrong has to always cite Roland Bainton’s ‘positive’ remarks about Luther if he cites any ‘negative’ opinions.” It’s ludicrous. I include these considerations where relevant. It matters not if they come from Bainton or someone else because Bainton is not my sole source, and my subject is Martin Luther.

Martin Luther’s stand on the bigamy of the Landgrave Philip of Hesses is also brought up by historians of all stripes, not just Catholic ones, and Catholic apologists like myself, because it was truly a scandal. Thus I cited one Lutheran scholar: “This double marriage was not only the greatest scandal, but the greatest blot in the history of the Reformation and in the life of Luther” (J. Kostlin, Life of Luther, Stuttgart: 1901, 2, 481, 486).

Remember, it was Luther and the early Protestants who were supposedly on a much higher moral plane than the corrupt Catholics and their church that was being opposed (Protestants describe their motivation as purely “reform,” but Catholics tend to view it as a revolt, insofar as it separated institutionally and adopted new doctrines not held before within institutional, historical Christianity).

There are several incidents over which one would rather draw the veil . . . The most notorious was his attitude toward the bigamy of the Landgrave, Philip of Hesse . . Luther counseled a lie . . . Luther’s solution of the problem can be called only a pitiable subterfuge. (Bainton, 292-293)

My critics on this score have confused the “whether” and the “why” once again. Since I was writing about the former, it was not necessary to include the latter. I certainly could have if I wanted to expand my paper and my own presentations of these incidents and beliefs, but it was not necessary, and failing to do so does not “prove” that I was misrepresenting Bainton, or using citations incorrectly and wrongly, because we are dealing with two different propositions, and a does not equal b.

If I were writing a paper entitled something like, “Roland Bainton’s Treatment of the Scandal of the Bigamy of Philip of Hesse” (which sounds more like an article in a theological journal rather than lay apologetics on a popular level), then I agree, I should have included all the additional clarifying and nuancing material. But I wasn’t doing that. This particular paper was an eleven-part treatment of some of the scandals and unfortunate consequences of the Protestant Revolt, not a treatise on Bainton’s in-depth opinions of Luther with regard to one particular incident.

The relevant question is: “what does a Catholic writing about Luther have to do in order to ‘exploit’ Luther”? Obviously, if I cite Bainton’s own opinion of the incident, then I am not exploiting Luther simply by doing that, lest Bainton would be guilty of the same thing, since he is the one I cited! This is obvious. So my critics can only nitpick and complain that I didn’t include massive context. But does this establish unethical, citation and misrepresentation? I don’t think so. I cited Bainton describing the scandal as one “over which one would rather draw the veil,” and a “most notorious” incident. He admits that “Luther counseled a lie” and was guilty of what “can be called only a pitiable subterfuge.” That’s the bottom line.

This is Bainton’s appraisal of the incident. He doesn’t agree with it or condone it. But as in the other cases we have treated, he does proceed (as a good biographer who wants to present the fullest, most nuanced picture of his subject) to try to explain why Luther did what he did, and offer some sort of semi-sympathetic rationale. One might call this “damage control” or “softening the blow” of the scandal. I have no problem with that, but I do have a problem with the charge that, simply because I didn’t include all of this material in what was simply an introductory treatment, that I was either misrepresenting Bainton’s opinion or “exploiting” Luther. The historical facts are unimpeachable, and no one denies them. This shouldn’t be controversial: this thing was a scandal anyway you look at it. I was simply pointing it out for those unfamiliar with it. I was under no obligation to examine the in-depth questions of “why” and the motivations, etc.

I cited a shorter part of Bainton’s opinion (we shall call it x) ; I shall call the longer, more detailed version y. Now does y somehow make x untrue when x is by itself? No, of course not, because x is part of y, so that if y is true, x is also. It is a fact along with an explanation of the fact (an action — counsel or advice — in this case). It would be like arguing about the following two propositions:

1. The night sky is black.

2. The night sky is black because the sun is on the other side of the earth; hence the sky is not illuminated by it on the dark side of the earth.

According to illogical and unreasonably demanding complaints, to cite the portion of #2 which is contained in #1 is to cite incompletely and misleadingly. But I vehemently deny this. #1 remains true whether it is explained or not, and it is not wrong to cite it, in and of itself. Thus, with regard to the discussion at hand:

1. Luther sanctioned bigamy and later lied about it. He was guilty of “pitiable subterfuge” in so doing.

2. Luther sanctioned bigamy and later lied about it, because of a, b, c, d, and e. He was guilty of “pitiable subterfuge” in so doing.

According to fallacious criticism, it is wrong to state #1, and this is an “exploitation” of Luther because it fails to contain the additional explanatory material contained in #2. This doesn’t follow, if the subject is whether Luther did in fact do what is described in #1. And all historians agree on this (whether Catholic, Protestant, or green-eyed, three-toed, redheaded, left-handed atheist historians). Most Christians are agreed that this was wrong for Luther to do. Therefore, it is not absolutely necessary to include a brief treatment of “what” he did, explanations, or rationales. None of these are particularly acceptable.

Part of the reason why I didn’t include such material was precisely because I assumed that my readers would not accept the reasons given, and that we all agreed that it was wrong. It needed no further explanation because none was adequate, anyway. I see nothing wrong with any of this.

I am not claiming to be a Luther biographer, nor to present an in-depth discussion of this one incident. I leave that to the biographers like Bainton. That’s their job, as questions of “why” are much more complex and difficult to ascertain than factual matters are.

What I specifically was referring to in my earlier papers, was the particular lie of misrepresenting and caricaturing opponents. It is unarguable that Luther did this, and it has been pointed out innumerable times, by historians of all stripes. For example, Desiderius Erasmus, considered the greatest scholar in Europe at that time, very much held this opinion:

I shall show everybody what a master you are in the art of misrepresentation, defamation, calumny and exaggeration . . . In your sly way you contrive to twist even what is absolutely true, whenever it is to your interest to do so. You know how to turn black into white and to make light out of darkness. (Hyperaspistes, [1526], I, 9, col. 1043)

I cited fellow Protestant “reformer” Martin Bucer writing to Heinrich Bullinger (Zwingli’s successor):

We have treated all the Schoolmen in such a way as to shock many good and worthy men, who see that we have not read their works but are merely anxious to slander them out of prudence. (Letter of 1535, Corp. ref., 10, 138)

They said this, not me. I’m just the messenger. If two Protestant “reformers” agree that such lying typified their “reform,” then who am I to disagree with their self-report? I believe them, especially knowing what I do about what went on in those days.

Crucial distinctions and simple logic have often been ignored, in the rush to “prove” that I “misuse” or “exploit” Luther (and Roland Bainton) for my own ends. I have not, as I think I have amply shown, above.