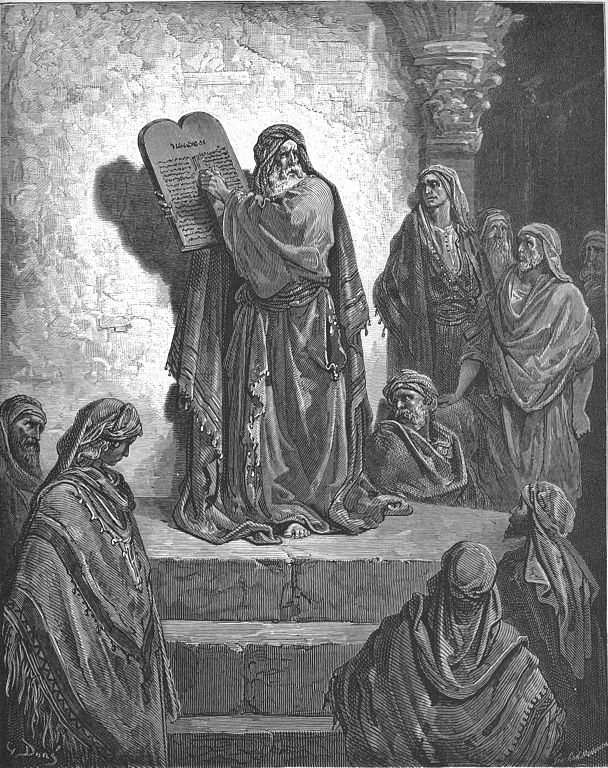

Ezra Reads the Law to the People (Neh. 8:1-12), by Gustave Doré (1832-1883) [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

***

This is from my 2002 book, More Biblical Evidence for Catholicism: the entirety of Chapter Nine (same title): pages 77-88 (I discarded some capitalizations used in the original, added capital letters in the sequential indented lists, and added some bolding of Scripture passages).

***

A Baptist man whom I met on the Internet, wrote a thought-provoking and well-researched essay, seeking to establish an analogy between the faith and religious authority structure amongst the Jews, as evidenced in the Old Testament, and the Protestant principle of sola Scriptura (Bible Alone as the final authority in Christianity).

I disagree with his assessment of the exclusive and final status of the written word of God over against the patriarchal, prophetic, and priestly proclamations of it, and its oral, traditional (and talmudic) aspects. I contend that he reached his conclusions with far too little and insubstantial evidence, whether biblical or historical.

There are many highly relevant factors which prove, in my opinion, that the Old Testament analogy is much more in line with both the early Church and present-day Catholicism (which developed from that early Church) and its notions of Church authority and tradition, than with the Protestant sola Scriptura rule of faith. I shall summarize these, each in turn:

1) THE JEWISH LAW, OR TORAH, WAS NOT EXCLUSIVELY WRITTEN DOWN

*

According to the reputable Protestant reference, Eerdmans Bible Dictionary [edited by Allen C. Myers, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1987 (from Bijbelse Encyclopedie, ed. W. H. Gispen, Kampen, Netherlands, 1975), 1014], oral communication and traditions in ancient Middle Eastern societies were much more common and standard than in our own time. The oral Torah was regarded as equal in authority to the written Hebrew Scriptures, and was believed to have been given to Moses on Mt. Sinai.

This vast collection of oral teaching was in due course codified in the Mishnah. Further interpretation of this text led to the Palestinian and Babylonian Talmuds. Halakhah, or legal teaching, is predominant in the Talmud (as in the written Torah). The task of the rabbis was to interpret the law of Moses, and to apply broad ordinances to individual cases.

The better (more biblically oriented) strains of Jewish tradition perfectly understood that the Law dealt with the heart, not just outward and/or ritualistic conformity. Jesus introduced nothing radically new in this respect, contrary to the jaded views of Judaism held by many Christians of all types. Jeremiah talked explicitly about the New Covenant.

It seems fairly certain from Holy Scripture itself that various writings and oral traditions were compiled and canonized at a later date (the time of Ezra and Nehemiah) and put into the form with which we are familiar (just as the New Testament itself was). I don’t think this implies either a denial of Mosaic authorship or of biblical infallibility.

Whether or not the Pentateuch was not codified until a later date is a different proposition from the question of Mosaic authorship. If later compilation was the case (as many conservative biblical scholars believe, I think), this no more means that such a process is illegitimate or untrustworthy than the late canonization of the New Testament brings into question Pauline authorship of his epistles. It is all merely development, not change in essence.

All these facts being true, and agreed upon by Protestant and Catholic biblical and historical scholars, it is hardly possible to make an analogy between the ancient Jewish authority structure and Protestantism.

The oral tradition was central from the beginning, and flourished even more after the canon of the Old Testament was finalized. At that point, the (mostly oral) methods and traditions which later crystallized into the written Talmud, intensified and continued on unabated for another six or so centuries. And then after that Judaism continued to discuss and comment on the Talmud itself, to this day. So the analogy is much more to Catholicism:

A) Oral law in Judaism corresponds to oral tradition in the New Testament (e.g., 2 Timothy 1:13-14; 2:2) and Catholic tradition.

B) In its interpretive and developmental aspects, Jewish oral law is similar to Catholic development of dogma and historical growth of conciliar and magisterial understanding of Christian teaching.

C) The Jews believed that the “oral Torah” went back to Moses on Mt. Sinai and ultimately to God, and was received simultaneously with the written Torah. Likewise, Catholics believe that Catholic tradition was received simultaneously from the apostles — who received it from Jesus — with the “gospel,” which itself was eventually formulated into the New Testament.The analogy to sola Scriptura, then, is impossible to maintain, since the Jews accepted the oral Torah as equally authoritative, the Canon of the Old Testament was only gradually formed (even the Pentateuch alone was authoritatively collected 500 years after David!), and authoritative and binding talmudic speculation and interpretation flourished even after the Old Testament had been completed and organized.

We believe that the authoritative Church is placed by God in the position as arbiter of doctrinal disputes and guardian of the apostolic deposit. Just as it verified the New Testament canon, so it acknowledges apostolic traditions and distinguishes them from corrupt, merely human ones.

Several tenets of Jewish religious belief developed subsequent to the finalization of the Old Testament canon, such as eschatology and angelology in particular — adopted virtually wholesale by the early Christians. The Sadducees were the Sola Scripturists (and liberals) of that time.

2) JEWISH ORAL TRADITION WAS ACCEPTED BY JESUS AND THE APOSTLES

*

A) Matthew 2:23: the reference to “. . . He shall be called a Nazarene ” cannot be found in the Old Testament, yet it was passed down “by the prophets.” Thus, a prophecy, which is considered to be “God’s Word” was passed down orally, rather than through Scripture.

B) Matthew 23:2-3: Jesus teaches that the scribes and Pharisees have a legitimate, binding authority, based on Moses’ seat, which phrase (or idea) cannot be found anywhere in the Old Testament. It is found in the (originally oral) Mishna, where a sort of “teaching succession” from Moses on down is taught. Thus, “apostolic succession,” whereby the Catholic Church, in its priests and bishops and popes, claims to be merely the custodian of an inherited apostolic tradition, is also prefigured by Jewish oral tradition, as approved (at least partially) by Jesus Himself.

C) In 1 Corinthians 10:4, St. Paul refers to a rock which “followed” the Jews through the Sinai wilderness. The Old Testament says nothing about such miraculous movement, in the related passages about Moses striking the rock to produce water (Exodus 17:1-7; Numbers 20:2-13). Rabbinic tradition, however, does.

D) 1 Peter 3:19: St. Peter, in describing Christ’s journey to Sheol / Hades (“he went and preached to the spirits in prison . . . “), draws directly from the Jewish apocalyptic book 1 Enoch (12-16).

E) Jude 9: about a dispute between Michael the archangel and Satan over Moses’ body, cannot be paralleled in the Old Testament, and appears to be a recounting of an oral Jewish tradition.

F) Jude 14-15 directly quotes from 1 Enoch 1:9, even saying that Enoch prophesied.

G) 2 Timothy 3:8: Jannes and Jambres cannot be found in the related Old Testament passage (Exodus 7:8 ff.).

Since Jesus and the apostles acknowledge authoritative Jewish oral tradition (even in so doing raising some of it literally to the level of written revelation), we are hardly at liberty to assert that it is altogether illegitimate. That being the case, the alleged analogy of the Old Testament to sola Scriptura is again found wanting and massively incoherent.

Jesus attacked corrupt traditions only, not tradition per se, and not all oral tradition. The simple fact that there exists such an entity as legitimate oral tradition, supports the Catholic “both/and” view by analogy, whereas in a strict sola Scriptura viewpoint, this would be inadmissible, it seems to me. It is obvious that there can be false oral traditions just as there are false written traditions which some heretics elevated to “Scripture” (e.g., the Gospel of Thomas).

This is precisely why we need the Church as guardian and custodian of all these traditions, and to determine (by the guidance of the Holy Spirit) which are apostolic and which not, just as the Church placed its authoritative approval on the New Testament canon. Holy Scripture is absolutely central and primary in the Catholic viewpoint, just as in Protestantism. No legitimate oral tradition can ever contradict Scripture, just as no true fact of science can ever contradict it.

Jesus is clear to distinguish what is called the “tradition of the elders” (Mark 7:3, 5) from the legitimate tradition, by saying:

Mark 7:8 (RSV) You leave the commandment of God, and hold fast the tradition of men. (cf. 7:9)

I would argue that neither commandment nor tradition per se are restricted to the written [medium]. Jesus contrasts human tradition with the word of God in 7:13, but that word of God is not only not restricted to the written Bible, but even identical to divine tradition, once one does some straightforward comparative exegesis.

Protestants wish to make a dichotomy, based on this passage, between oral and written tradition, whereas Jesus, I think, is clearly contrasting human (false) tradition and divine tradition, whether oral or written. I think the notion that any of this proves sola Scriptura is eisegesis at best and special pleading at worst.

There were also many false books parading as Scripture in the early Christian period. If falsity alongside truth is a disproof of that truth (and its medium), then the Protestant Scripture Alone view is just as fatally flawed as the Catholic view. Protestants needed the authoritative Church to proclaim the canon of the New Testament, just as we need it to determine true apostolic tradition.

3) JEWISH “ECCLESIOLOGY” INCLUDED AUTHORITATIVE INTERPRETATION

*

The Jews did not have a “me, the Bible, and the Holy Ghost” mindset. Protestants have, of course, teachers, commentators, and interpreters of the Bible (and excellent ones at that – often surpassing Catholics in many respects). They are, however, strictly optional and non-binding when it comes down to the individual and his choice of what he chooses to believe. This is the Protestant notion of private judgment and the nearly absolute primacy of individual conscience (Luther’s “plowboy”).

In Catholicism, on the other hand, there is a parameter where doctrinal speculation must end: the magisterium, dogmas, papal and conciliar pronouncements, catechisms — in a word (well, two words): Catholic tradition. Some things are considered to be settled issues. Others are still undergoing development.

All binding dogmas are believed to be derived from Jesus and the apostles. Now, who did the Jews resemble more closely in this regard? Did they need authoritative interpretation of their Torah, and eventually, the Old Testament as a whole? The Old Testament itself has much to “tell” us (RSV):

A) Exodus 18:20: Moses was to teach the Jews the “statutes and the decisions” — not just read it to them. Since he was the Lawgiver and author of the Torah, it stands to reason that his interpretation and teaching would be of a highly authoritative nature.

B) Leviticus 10:11: Aaron, Moses’ brother, is also commanded by God to teach.

C) Deuteronomy 17:8-13: The Levitical priests had binding authority in legal matters (derived from the Torah itself). They interpreted the biblical injunctions (17:11). The penalty for disobedience was death (17:12), since the offender didn’t obey “the priest who stands to minister there before the LORD your God.” Cf. Deuteronomy 19:16-17; 2 Chronicles 19:8-10.

D) Deuteronomy 24:8: Levitical priests had the final say and authority (in this instance, in the case of leprosy). This was a matter of Jewish law.

E) Deuteronomy 33:10: Levite priests are to teach Israel the ordinances and law. (cf. 2 Chronicles 15:3; Malachi 2:6-8 — the latter calls them “messenger of the LORD of hosts”).

F) Ezra 7:6, 10: Ezra, a priest and scribe, studied the Jewish law and taught it to Israel, and his authority was binding, under pain of imprisonment, banishment, loss of goods, and even death (7:25-26).

G) Nehemiah 8:1-8: Ezra reads the law of Moses to the people in Jerusalem (8:3). In 8:7 we find thirteen Levites who assisted Ezra, and “who helped the people to understand the law.” Much earlier, in King Jehoshaphat’s reign, we find Levites exercising the same function (2 Chronicles 17:8-9). There is no sola Scriptura, with its associated idea “perspicuity” (evident clearness in the main) here. In Nehemiah 8:8: “. . . they read from the book, from the law of God, clearly [footnote, “or with interpretation”], and they gave the sense, so that the people understood the reading.”

So the people did indeed understand the law (8:12), but not without much assistance — not merely upon hearing. Likewise, the Bible is not altogether clear in and of itself, but requires the aid of teachers who are more familiar with biblical styles and Hebrew idiom, background, context, exegesis and cross-reference, hermeneutical principles, original languages, etc.

H) I think all Christians agree that prophets, too, exercised a high degree of authority, so I need not establish that.The Catholic Church continues to offer authoritative teaching and a way to decide doctrinal and ecclesiastical disputes, and believes that its popes and priests have the power to “bind and loose,” just as the New Testament describes. Protestantism has no such system.

The Old Testament and Jewish history attest to a fact which Catholics constantly assert, over against sola Scriptura and Protestantism: that Holy Scripture requires an authoritative interpreter, a Church, and a binding tradition, as passed down from Jesus and the apostles.

4) PROPHETS’ SPOKEN WORDS CONSTITUTED THE WORD OF GOD

*

Protestant arguments in favor of sola Scriptura frequently contain the gratuitous assumption that word of the Lord, word of God, etc. is always or usually a reference to the written word (i.e., Holy Scripture). This simply is not the case. In fact, the exact opposite is true, as a good concordance (“word”) will quickly confirm. In the very verse my Baptist correspondent was trying to use as an example of the written word (Daniel 9:6), one can readily observe this. It reads: “We have not listened to thy servants the prophets, who spoke in thy name to our kings, our princes, and our fathers, and to all the people of the land.”

It seems to me that the most straightforward primary meaning of this passage is as a reference to oral proclamation. The Old Testament “Church” and its Torah perpetuated itself — roughly up to the time of Ezra (5th century B.C.) primarily by oral and liturgical (Temple, priestly) tradition. Just as in Catholicism, Scripture for the Jews (to the extent that it was recognized as such — which was a process) was central but not the be-all and end-all of faith, or the sole rule of faith for atomistic individuals.

Like any other book, it needed (and needs) an interpreter, and when differences of interpretation arise, there is the need of a binding authority to settle the matter, so that chaos and relativism may not reign amongst God’s covenant people.

A prophet’s inspired utterance was indeed the word of the Lord, but it obviously was not written as it was spoken! Most if not all prophecy was first oral proclamation, but it was just as binding and inspired as oral revelation, as it was in later written form (i.e., those prophecies which were finally recorded — surely there were more). In this sense truly inspired prophecies are precisely analogous to the proclamation of the gospel, or kerygma, by the apostles.

Both the gospel and virtually the entire New Testament (excepting perhaps Revelation) began as oral preaching (notably, Jesus Himself wrote nothing), and was increasingly recognized by the early Church as inspired and hence Scripture. But it was just as binding before it was finally proclaimed Scripture in 397 A.D. It didn’t become Scripture because the Church said so; rather, the Church authoritatively proclaimed, in effect, that these particular books are inherently Scripture and divinely inspired.

Sola Scriptura couldn’t possibly be the formal authoritative model for Jews often without a written Scripture, nor for the early Church up to 397 AD! This is obviously the Catholic model of authority. Just as the Catholic Church verified the extent of New Testament Scripture, so it has the burden of orthodox interpretation of that Scripture, in order to maintain true apostolic doctrine. Sola Scriptura is historically (and logically and biblically) self-defeating.

Like its Jewish predecessor, this state of affairs (the process of canonization) is not sola Scriptura: it is tradition and binding Church authority which has the prerogative of determining the parameters of what is of its own essence Scripture.

The Church doesn’t create Scripture (which is “God-breathed”), but merely recognizes it. It has to recognize it. That is the whole point. It is practically necessary. Tradition and binding Church authority also claim possession of the apostolic deposit and final say as to what are true Christian doctrines, and which are to be rejected as false.

When Peter interpreted Old Testament Scripture messianically and “Christianly,” in the Upper Room (as recorded in Acts 2), his word was just as authoritative and inspired as when it was set down in writing later. Throughout the book of Acts we see St. Peter and St. Paul exercising apostolic authority and preaching, not handing out Bibles.

Prophets were the Old Testament equivalent of apostles. Apostles passed on their office and authority (albeit in less spectacular and “inspired” form, no doubt) to bishops. And so the early Church had the notion of apostolic succession and apostolic tradition, which was the bottom line in doctrinal disputes — not simple recourse to Holy Scripture, as if there were no differences of opinion on it, and as if it were “perspicuous.”

Virtually all the heretics of the early Church period based themselves on Scripture Alone, but a skewed interpretation of the Scripture (and tradition). This was particularly true, I believe, of the Marcionites, Arians, and Nestorians.

5) PHARISEES, SADDUCEES AND THE NATURE OF TRUE JEWISH TRADITION

*

Many people do not realize that Christianity was derived in many ways from the Pharisaical tradition of Judaism. It was really the only viable option in the Judaism of that era. Since Jesus often excoriated the Pharisees for hypocrisy and excessive legalism, some assume that He was condemning the whole ball of wax. But this is throwing the baby out with the bath water. Likewise, the Apostle Paul, when referring to his pharisaical background doesn’t condemn Pharisaism per se.

The Sadducees, on the other hand, were much more “heretical.” They rejected the future resurrection and the soul, the afterlife, rewards and retribution, demons and angels, and predestinarianism. Christian Pharisees are referred to in Acts 15:5 and Philippians 3:5, but never Christian Sadducees. The Sadducees’ following was found mainly in the upper classes, and was almost non-existent among the common people.

The Sadducees also rejected all “oral Torah,” — the traditional interpretation of the written that was of central importance in rabbinic Judaism. So we can summarize as follows:

A) The Sadducees were obviously the elitist “liberals” and “heterodox” amongst the Jews of their time.

B) But the Sadducees were also the sola Scripturists of their time.

C) Christianity adopted wholesale the very “postbiblical” doctrines which the Sadducees rejected and which the Pharisees accepted: resurrection, belief in angels and spirits, the soul, the afterlife, eternal reward or damnation, and the belief in angels and demons.

D) But these doctrines were notable for their marked development after the biblical Old Testament canon was complete, especially in Jewish apocalyptic literature, part of Jewish codified oral tradition.

E) We’ve seen how — if a choice is to be made — both Jesus and Paul were squarely in the “Pharisaical camp,” over against the Sadducees.

F) We also saw earlier how Jesus and the New Testament writers cite approvingly many tenets of Jewish oral (later talmudic and rabbinic) tradition, according to the Pharisaic outlook.

Ergo) The above facts constitute one more “nail in the coffin” of the theory that either the Old Testament Jews or the early Church were guided by the principle of sola Scriptura. The only party that believed thusly were the Sadducees, who were heterodox according to traditional Judaism, despised by the common people, and restricted to the privileged classes only.The Pharisees (despite their corruptions and excesses) were the mainstream, and the early Church adopted their outlook with regard to eschatology, anthropology, and angelology, and the necessity and benefit of binding oral tradition and ongoing ecclesiastical authority for the purpose (especially) of interpreting Holy Scripture.