. . . Including a Searching Examination of Various Flaws and Errors in the Protestant Worldview and Approach to Christian Living

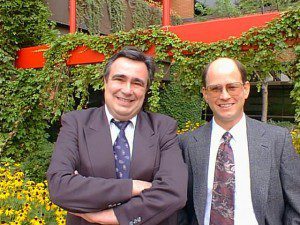

Al (left) with fellow Michigander and good friend, Steve Ray, in the 1990s [from Steve Ray’s website: 9-30-13]

(edited and transcribed by Dave Armstrong from Al’s talk dated 4-26-92)

Al Kresta was raised Catholic, converted to evangelical Protestantism, became a prominent talk show host and a pastor, and then reconverted to Catholicism. He is the author of Why Do Catholics Genuflect?: And Answers to Other Puzzling Questions About the Catholic Church and host of Kresta in the Afternoon, which is syndicated nationwide. His story was one of eleven conversion testimonies included in the bestseller Surprised by Truth (the last story, and right after my own). Al and I have been friends since 1982, and he was my own pastor shortly before I converted to Catholicism. See also, Catholic apologist Steve Ray’s article, “My Friend Al Kresta: Story of an Unsung Hero and Modern-day Prophet” (9-30-13).

This is one of the most remarkable, “meaty,” thought-provoking conversion stories and extended criticisms of Protestantism (though within an overall ecumenical attitude of respect and affection), that I have ever seen. The following is an edited version of Al’s talk, which took place at my house on 26 April 1992. It lasted about 3 1/2 to 4 hours, and every minute was interesting and informative. I hope you will enjoy it as much as I have (many times). Rather than include lots of ellipses (. . .), breaks in the talk (where I have edited) will be indicated by new paragraphs (though not every such break means that I have edited).

***************

This is why I returned to the Catholic Church, not necessarily why you ought to. I’m more than happy to make a presentation some night to say why you ought to. This is my story of how I returned.

I was raised Roman Catholic, in a church-going, sacrament-receiving home. I have, really, very positive memories of my upbringing. I liked it. It was kind of mysterious. I remember going there, and there was the Eucharist, and that was Jesus, and the church was in hushed silence. There was this awe.

I had that sense of the sacred from my experience in the Church. My first confession, I still remember as one of the most powerful spiritual experiences I ever had. I remember emerging from the confessional and leaving the church on a Saturday afternoon, and finding myself floating off the ground. I felt that I was united with God, that my sins were forgiven; it was a great experience, and I remember it to this day. That has a lot to do with my early years; basically a positive experience. Once I hit my teen years, it was a different story. It was the mid-60s. I graduated from high school in 1969, and during those high school and teen years I went the way that a lot of kids did during that period.

I have one other experience from that adolescent time that I think is probably significant. In May 1969 I was doing quite a few drugs and this was a particular LSD trip that I took. It was a death trip, and I thought I was dying. I was brought to the hospital. It turns out there was nothing wrong with me. I was just going crazy. I remember that night, thinking I was dying, and calling on Mary — being able to fall asleep after hours of struggle. I woke up the next morning like the slate had been made clean. It was great.

I think I only had a few minor drug experiences after that. I don’t know what to make of that, really. It was one of those odd experiences that you just have, and you forget. It didn’t form any theological backdrop for me, subsequently – trying to search, after those drug experiences for what was real, and true, and good. Catholicism wasn’t on the list, so I still don’t know what to make of that experience, spiritually or psychologically. I still believed there was something there. I was not an atheist by any stretch of the imagination. A pagan of some sort, but not an atheist, I would say.

Let me jump to the time I began following Jesus as an adult. That was in 1974. I was 23, almost 24 years old, I guess. When I began following Jesus, and accepted the authority of Scripture, I guess the key was that it was a conversion to the authority of Scripture, as much as it was to a person. Because of the spiritual confusion that I had had, in the New Age movement, it was imperative that I get away from a subjective, internal test for truth, and find truth independent and external to myself, and that’s what the Bible provided for me. It gave me a way of testing competing truth claims. I was really happy to begin Bible study.

I had a good pastor . . . I thought, naively, that if you knew the original languages [of the Bible], all these denominational things would fall by the wayside, you’ll get to the real truth of it, and right at the beginning of my discipleship he [my pastor] made it clear that you could know the Hebrew and the Greek and you would still have all these denominations. The Bible is authoritative, but even knowing the original languages won’t settle all these issues. You’re gonna have to live with ’em.

I pretty much adopted the Bible Alone as my authority. Baptists were in. Lutherans were kind of out, because they had robes and believed in baptismal regeneration. Reformed people and Presbyterians were pretty good, but you couldn’t figure out why they baptized infants and they didn’t believe in the Millennium. They were good for a lot of things, but not for everything. And pentecostals were puzzling, too, because they believed the Bible a lot but they seemed to get too much into this experiential thing, and you couldn’t make out what they were saying, half the time -this tongues-speaking.

Reformed and Presbyterian people provided the best scholars for the Bible-believing movement, but they baptized infants and they didn’t believe in the Millennium. So I guess I was a fundamentalist in the early years because it was a narrow focus. But my pastor had a great heart and embraced many many people. That was a good spirit.

The people who influenced me in my reading, then, were Francis Schaeffer — probably no greater single influence in my life at that point, than him; C. S Lewis, Josh McDowell. I was very influenced by the campus movements, like Campus Crusade for Christ, Inter-Varsity . . . I spent time with friends of mine, convincing them to leave the Catholic Church, and I spent time with priests. I wasn’t hostile to Catholicism; I want to make that clear, but the priests I met were dumb. I had just been reading the Bible for about a year, and I could turn them into doctrinal pretzels. They really didn’t know their stuff.

Most of the priests I met were really nice guys, and that’s about all that I could say for them. Their mentality was sort of an “all you need is love” mentality. But at least you better define “love” a bit. What does that mean? It drives you back to the cross. Now, I might think very differently if I met them now, but at the time it seemed like they were not doctrinally-oriented, and they always kept stressing, too, how much the Church was changing, when for me at the time, that was really a negative. I wanted something that was firm, and unyielding, and for me that was the Scripture.

There were people who came out of the Catholic Church as a result of my work. I was suspicious of Roman Catholicism for all the traditions that it had. I got tired of meeting Catholics who kept complaining about being Catholics; about birth conrtrol, this, that, and the other thing, or divorce. My answer always was, “get out! Why do you want to be there, then? Just get out!” I couldn’t figure it out. I still have similar feelings about that. It’s one thing to have respectful disagreements, conscientious objections, and things like that, but don’t go around moaning about it; it stirs up trouble.

I was still real young, not knowing much about Church history. I was like most Protestants: you think the Church began with Jesus and Paul, skipped over to Martin Luther, and then you hit Billy Graham. So my roommate [who owned a complete set of the Fathers’ writings] started telling me about Polycarp, and Ignatius and I thought, “this is very interesting stuff.” He stressed that the early Church believed in the Real Presence. Well, I couldn’t deal with all this. I was interested in evangelism, and Real Presence was not really important.

I continued the work of evangelism, and a number of people came into relationship with Christ, and I noticed right away that the community I was a part of, was in some ways a lot less spiritually motivated than the New Age group that I had come out of, and that was very disturbing to me. The people who I began worshiping with were generous and kind, and they helped me out, but their lives were not oriented to living out their convictions to the same degree as the New Age group I was with before I began following Jesus.

I also saw tremendous disunity among Christians. They were always fighting about things that, in my naivete, I thought were non-essentials. I saw a lot of superstition, very odd pastoral practices: large numbers of arranged marriages, . . . I was also becoming very uncomfortable with evangelicalism’s a-historicism. It had no sense of history!

There was no way of writing off the Catholic tradition. It had to be received as legitimate, at least to a certain extent. It was a matter of now having to say, “the Tradition itself does preserve the objective value of Jesus’ atonement.” So I could no longer write the Catholic tradition off as somehow sub-Christian. But still, Catholicism was not an option, for many many reasons: superstition, doctrinal laxity, so many things.

I began using the Episcopal Book of Common Prayer. That was very helpful: the elegance of the language, the loftiness of the sentiments, the clarity of the prayerful intention, convinced me that the problem with form prayers were not the forms themselves, but with people who were incapable of filling the forms with genuine piety and conviction.

Because of all these various influences upon me, I never chose a theological tradition. I really couldn’t sum myself up as a Lutheran, or a Reformed, even a Baptist. I never found a systematic theology that I was comfortable with. I was more practically and evangelistically-oriented. I didn’t have time to work through all this. In fact, it’s only been since I got out of the pastorate, that I began thinking systematically; theologically. Most of my theology has always been task-oriented. I went to churches, but I was never a member of a church until I

pastored one.

After I got out of college, I began managing Christian bookstores, and that was an important influence. It looked to me like there were sheep and goats everywhere. It became increasingly difficult to decide who was in and who was out. You couldn’t use the old shibboleths anymore: “are you born again?,” because, first of all, anybody could say they were, and secondly, the Bible doesn’t make a big issue out of being born again. It really doesn’t. It uses a lot of different images: a half a dozen to a dozen different images to represent salvation. The reason why [they use the terminology] “born again” is because it’s part of their tradition! [laughter] And they’re comfortable with it. I had to broaden more and more to embrace more and more people who I understood as my brothers and sisters.

I was also influenced a lot by this notion that C.S. Lewis popularized, called “mere Christianity.” It was very very helpful to me in the early years. Later on, when I became a pastor, I found that it wasn’t very helpful at all. But in evangelism it was great, because you were able to cut through all the theological debates and the various traditions and try to bring a person to make a decision about Jesus. You didn’t have to defend baptism, or the Eucharist. You didn’t have to defend anything but the deity of Christ, and the fact of His atonement, and the need that you have to trust Him. And that was what I tried to live off, for a long long time.

Friends of mine started asking me to teach about cults. My wife’s cousin got involved with the Way International (Jesus is a created being; classic Arianism). I offered to write a response to the Way International for Sally’s cousin. I was disturbed, because the answers that I hoped I would find in the Scriptures were not as self-evident as I thought they would be. The doctrine of the Trinity is not as self-evident in the Scripture as most cult researchers would like you to believe. It takes a good deal of reflection, collating various verses, logical analysis, and prayer, to come to the conclusion that God is Triune. And I could see why Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Way International, relying on the Bible alone, might come to the conclusion they did. I thought they were wrong; I didn’t think they offered the best explanation of the biblical material, but I could see a good faith effort with some intellectual error mixed in, could lead them to the conclusion that they had. On what basis could I exclude them from the faith?

I learned the value of creeds and councils. The ones who were arguing that Jesus was not God, were arguing that they were the ones who reached their conclusions on the Bible alone. It was the heretics who said they were relying on the Bible alone, and it was the orthodox, the Catholics, who were appealing to a living Tradition. That was disturbing to me. I thought what was interesting was that the Church didn’t argue on the basis of the Bible alone. The Church argued on the basis of the Bible and the history of teaching. That was one big thing that hit me.

I also read the apostolic Fathers [around this time], and I couldn’t figure out how they got to be Catholic so quickly after the apostles left. I was amazed at how Catholic Ignatius was. He calls the Eucharist the “medicine of immortality.” Nothing symbolic about it; there’s actually something good for his soul. He has bishops all over, who are supposed to be obeyed. What happened in ten years?! You’ve got sacramentalism coming in, ecclesiasticism coming in . . . I couldn’t figure out how the Church could have been so corrupted and filled with false tradition. But they keep appealing to what’s gone on before. This was troubling to me, because some of the distinctive doctrines of Catholicism were already believed by the apostolic Fathers. I was also troubled because on the basis of the Bible alone, you could just as well end up with the heretics, as the orthodox. I didn’t know what to do with this.

Another big thing hit me at that time, and that was the idea of development. I could see in reading the Bible, that various doctrines which appear full flower in the New Testament, are mere seeds in the Old Testament. I asked myself that if God was interested in developing doctrine in the canon of Scripture, why isn’t He interested in it after the closing of the canon? The doctrine of the afterlife [for example] was vague in the Old Testament. It isn’t until one of the last books in the Old Testament, that you end up with clear teaching on the resurrection (Daniel). You can find the doctrine of the atonement developed similarly. I began reading Newman, for a variety of reasons. I was impressed with him as a stylist and as a devout man of God, but for whatever reason, I was unpersuaded. I was still afraid of the idea of doctrinal development outside of the New Testament.

Sally (around 1980 or 1981) bought me a two-volume biography of the evangelist / revivalist George Whitefield. I found a great man, who was great friends with John Wesley, and both of them practiced forms of superstition. I was amazed. They were characters. This was not a debunking kind of biography at all. If anything it was a Protestant piece of hagiography. Wesley made some major life decisions by casting lots. He was not the “man in control” that he is often presented as being. Wesley and Whitefield are two of the great figures of evangelicalism. They were revivalists. And they were marvelous people. I was inspired a great deal by the biography.

But at the same time I had to deal with the fact that these guys practiced forms of superstition in the conduct of their lives, that if I saw today, I would say “How foolish; how silly.” I was living upstairs from a Mexican couple, who were Roman Catholic, and they were involved in all kinds of unusual devotional practices, none of which I paid much attention to, but wrote them off as superstitious. Then I find out that Wesley and Whitefield practiced some forms of superstition as well. So you come up with this “immoral equivalency.”

Shortly after this I ended up hospitalized for depression, twice. From ’82 to ’85, I was having to take medication, and to live a life in which I was pretty much a practical atheist. The universe seemed utterly meaningless and without coherence and there seemed to be no God, no purpose, and no meaning. I came out of that in May of 1985. I said to God, “you know, it’s been three years now, and you know I want to serve You, but I’m not convinced You’re even there anymore, and this is becoming a futile effort. I’ve got to get along with my life. I’ve got a wife and daughter here.”

I went down to Thomas Merton’s Abbey Gethsemane. I’d read Merton’s Seven Storey Mountain and thought it was a great story. When I went down there it was sort of a do or die effort. I was saddened; I wasn’t angered about God. I was saddened that He apparently treated His friends so badly. And He probably didn’t exist, and this is just life. It’s pointless, but we have to pretend that there is a point to it.

Lo and behold, after three years of darkness — light. During my stay down there I had three visions, or images, if you will, which were the only rays of light that had given me any sense of meaning or purpose through that terrible period of darkness. I could go off and speak on this for days, because it was so remarkable. I did the Liturgy of the Hours down there, and talked to a priest, and when I came out, my life began to reassemble itself. I still had some difficulties, but overall, I was back on track again. It was a great experience. I started reading theology and Scripture again, and began to pray again.

Luther is really the father of the way evangelicals preach on justification. The apostle Paul was not concerned with the same things Luther was concerned with. If you analyze Luther’s experience: the questions he was asking God: they’re not the same things the apostle Paul was asking of God. Luther has been like a lens that Protestants have put on to read the New Testament. Luther was preoccupied with how he could gain acceptance by a gracious God. This was his question.

But the apostle Paul doesn’t seem too concerned about that at all. He has a rather robust conscience before God. He knew that God was gracious. He never pleads with either Jews or Gentiles to feel an anguished conscience, and then release that anguish in a message of forgiveness through Christ. He never urges that kind of revivalistic experience upon his readers. When Paul does speak of himself as a serious sinner at all, it’s not because of his existential anguish under the righteousness of God in general, but very specifically, because not having recognized that Messiah had come in Christ, he had persecuted the Church, and fought the opening of God’s covenant to the Gentiles. That was Paul’s issue. It wasn’t personal acceptance before God. Luther was asking questions the apostle Paul really wasn’t concerned about.

The Jews understood that salvation was granted by God’s electing grace, not according to a righteousness based on merit-earning works. Most Protestant scholars since Luther have read Paul as saying that Judaism misunderstood the gracious nature of God’s covenant with Moses and perverted it into a system of attaining righteousness by works. Wrong! That’s not what they did. That was Luther’s problem, not Paul’s problem. The Jews weren’t boasting that they could attain righteousness by doing works. They were boasting that they were God’s chosen — by grace.

Paul agonized over the social nature of the Church. Luther, on the other hand, agonized over the personal assurance of God’s acceptance. In other words, Luther, by having misunderstood Paul, developed a whole new approach to religion. The irony of it is, he probably developed it out of Catholic corruptions in the Middle Ages. [laughter] Paul wasn’t that concerned about individual salvation. That wasn’t his issue. The issue was the nature of the body: the community. This [realization] allowed me to establish even more distance from the evangelical tradition (around 1985).

[recounts how bookstore customers wanted Jack Chick materials, which his stores refused to sell] I was hit again with how anti-Catholic fundamentalism and evangelicalism is. There is a deep streak of bigotry that runs through it. I wasn’t that worried about it, though, because in my own mind I could write that off.

The question of the canon of Scripture had always bothered me, almost from the beginning. Where’d it come from? It seemed like such an obvious question that I figured there’s gotta be lots of good answers to it and that everybody must know why we have a canon of Scripture. Jesus left us with a community before He left us with a book. I found the appeal to an authoritative Church far more honest and consistent than an appeal to an authoritative Bible. So I ceased to defend the canon of Scripture with any enthusiasm — except by an appeal to an authoritative Church. The problem was I didn’t know where this Church was. It couldn’t be the Roman Catholic Church. It just couldn’t be. There’s too many problems there.

I got this call to pastor a church (Shalom Ministry) in 1985: a job that eventually would lead me to the Catholic Church. I didn’t know it at the time. I was looking for this church and I figured that since it wasn’t out there, I’d make it myself. And that’s what ended up happening. Since there was no church that I felt conformed to a biblical shape, that I might as well use this opportunity to experiment a bit.

I really did believe when I entered pastoral work, that you had only two choices: it seemed to me that you could go the independent church route, where every pastor is their own pope, and they’ve got the Bible alone to work with, or you ought to get honest with yourself, and go ahead and become Orthodox or Catholic, and accept an authoritative teaching church. I really didn’t like all the mediating positions in between. Why do you want denominations? Why not — if you’re going to accept the authority of a tradition — accept the authority of the Orthodox or Catholic traditions, which at least have a developed theology of tradition. Tradition is inevitable.

I thought that the real problem with the evangelical churches was lack of doctrine or Scripture study, and good preaching, and I quickly found that that wasn’t the case. There’s probably too much teaching. You get up on a Sunday morning, and you prepare a message, and you would preach, and rain on ’em, and it’d be forgotten by the week after, and you’d wonder why you’re doing this: your best ideas and study, pouring it out on them. But what people needed was spiritual apprenticeship, discipleship, an elder or spiritual leader to model the Christian life for them. If they needed preaching, let ’em listen to John MacArthur, or buy a book of sermons. You can do that now.

I did see that my approach was destined to futility. And I saw a lot of moral failure. That didn’t scandalize me. I knew who was sleeping with who; who was lying about who, and I would confront it, and sometimes people would repent, and sometimes they didn’t. But what scandalized me was the ability to use what I called “the language of ultimacy”: like “the Lord told me,” or “are you sold out for the Lord?,” or “we have nothing to live for but saving souls”: always this kind of high-pitched language of commitment, which didn’t bear any tangible relationship to the lives that people were leading.

And these people were not intending to be hypocrites. It was just the function of evangelical language. It was their symbol-system. This was the way they talked. The problem was that the language began to substitute for the reality, so you could talk about your commitment to soul-winning, or how missions has to be number one, and yet sit home and not do a darned thing. But you knew the language. It was just part of the tradition: the revivalistic tradition. It was a way of applying a spiritual anesthetic.

We like to think of ourselves in the evangelical tradition as other than mere churchgoers. You tended not to exercise the judgment of charity towards the churchgoer, and to say “they’re not part of us until they prove they’re born again.” And I saw this as a spiritual arrogance, but it was more a function of language than of the heart of people.

One thing that happened as I began pastoring is that I began to see the failure of “mere Christianity.” It was a great discipleship tool. But it was a terrible curse when you wanted to disciple people. It was good for breaking down barriers between Christians and getting them to talk to one another and respect one another, but not very good in trying to teach people a worldview or trying to grow in grace. I would call it the “inner contradiction of mere Christianity.” It is unintentionally dishonest and gives the wrong impression about matters vital to Christian growth and maturity. In a sense you’re selling people a bill of goods. You’re hooking them with a minimalist conception of the faith, and then once they get in, you start laying on them the obligations. Nobody means any harm by it, . . .

By discounting as non-essential to Christianity, anything that would interfere with the evangelistic task, we imply to the convert that only those things which he assents to at conversion, are the essential things. Thus, major biblical doctrines like the Church, worship, work of the Holy Spirit, even the authority of Scripture, end-times teaching, even ethical teachings like our obligation to the poor, the unborn: all those things are minimized and therefore considered secondary and non-binding to the convert. People are called to Christ the head, but it’s disconnected with Christ’s body. To come to Christ in the New Testament always meant coming into a particular community; accepting this community and them accepting you, and that also meant the tradition and the way of life of the community. This approach cannot sustain a church or a tradition, and not enough to give much direction in life’s decisions.

“What you are converted by is what you are converted to.” Since the evangelical principle is the Bible alone and the Bible doesn’t use the word Trinity and doesn’t refer to abortion specifically, how important can these things be? That’s the way the argument will go, and I hear it all the time. Free church Protestants have no reliance upon institutionalized teaching authorities. The authority in their mind is them, the Spirit of God, and the Word of God. And quite honestly, that’s wrong. That’s not biblical. The biblical pattern, is me, the Spirit of God, the Word of God, and the Church of God. The community is an essential dimension of the biblical experience. So you end up with what? Private interpretation. It’s me, the Spirit, and the Bible.

And while evangelicals say you should be a member of a church (Billy Graham will say that), usually converts are made by driving a wedge between the convert and the Church. Often, you’ll hear in evangelistic presentations: “baptism isn’t important, this isn’t important, denominations aren’t important. What’s important is you and your relationship with God.” In the right context, that point can be made, but the subtext of the message is “once you get saved, it’s you and God.” So this private interpretation is really overwhelming. We become “theological Atlases.” No one person is able to do that against the spirit of the age. You need the full body to teach authoritatively. You can’t do it yourself. You can’t do it: not authoritatively. To sit there as a papal substitute and do it, independently of, say, the college of bishops, research universities, is wicked. But it’s done, all the time.

Great evangelical leaders that have come up this century, who have been very helpful: people like Francis Schaeffer, who I owe an enormous debt to; notice how they function within the evangelical community. They don’t function as the leader of a church, but as authoritative celebrities. Their audience has no recourse to hold them accountable. There’s no structure set up.

Mere Christianity also undermines confidence in the local church, or (if you believe in them) the denomination, which is secondary to one’s primary commitment to Christ. But this is schizophrenic. It pits the head against the body, and ultimately it betrays Jesus Who says the gates of hell would not prevail against His Church, the body. These things are connected. The head doesn’t regard the body as a “necessary evil” like many evangelicals do. They think that you gotta go somewhere to get Bible teaching, so you go to church. [The Church] is secondary only in the sense that it flows from my commitment to God, and is entailed in that commitment. How ecumenical is mere Christianity, if it removes the doctrine of the Church, which is central to two of the three Christian traditions? So it really isn’t very fair to Orthodoxy and Catholicism. [It amounts to saying that] God is not able to adequately reveal Himself through the things that he has made, or the people that He has called. It’s a slap in the face of God.

Mere Christianity is dishonest in that it requires a soft-peddling of differences between Christians. And it belittles our brothers and sisters in the past. When we say “let’s transcend and rise above all these denominational distinctives,” we are actually emasculating the various Christian traditions. The very things that Wesley and Luther and Calvin found as solutions to the problems of their day, we’re saying, “it’s not important. Let’s just get above ’em. It doesn’t matter that these brothers regarded these things as central and essential to the Christian life. We’re so superior to them that we can just rise above it.”

And I find that that’s a very belittling approach to these men and women. Accept them on their own terms. Disagree with them if you have to. But don’t say they’re irrelevant. Within their systems, these denominational distinctives are meant to be solutions to serious problems in the Christian life, and when we don’t take them on their own terms, then we’re regarding these men and their traditions as pathological, petty, or unwise. I think Luther was wrong [about justification], but I can’t say he’s unimportant, you see. And that’s what I don’t like about “mere Christianity.”

By 1987 I was pastoring a church and hosting an evangelical talk show, but I found my heart growing really hard and full of disdain for the tradition that I was supposed to be serving, and I knew that wasn’t good, so I made a list [of some of my criticisms] in my journal:

1. Lack of a coherent worldview, which leads to a denial of Christ’s Lordship.

2. Methods which cheapen the gospel and promote confusion in converts (“what you are converted by is what you are converted to”).

3. Manichaean dualism which is inconsistently and conveniently applied to beat others with one’s own taboos.

4. Cultural naivete which presumes the priority of Anglo-Saxon culture and an ignorance of ancient biblical culture and its distinctive marks over against its Mesopotamian, Roman, and Greek backgrounds.

5. Flippancy towards divine mystery and paradox; a loss of the sacred, which is best seen in a casual attitude towards the sublime and lofty.

6. Meaningless and saccharine expressions of piety, and a retreat into jargon.

7. A suspicion of intellect.

8. Evangelicalism has become so shaped by modernity that it is privatized, secularized, and has adopted pluralism.

9. A naive pride in its own tradition of traditionlessness.

10. Duplication of effort among institutions.

11. Individualistic to the point of rebellion.

12. Too many personality cults.

13. Ignorant of its own history.

14. Bizarre prophecy schemes which create escapist mentalities and loss of a stable future orientation.

All those things were weighing on my heart: bang bang bang bang. I realized “why am I doing this? My heart is not really in the revivalistic tradition anymore.”

There’s no way of escaping tradition, at two levels: sociologically and theologically. Sociologically, why does the church exist? Once you’re inside a community of people, you begin doing things a certain way. You fall into certain traditions. They do develop. There’s no avoiding them. And the traditions usually exist for fairly good reasons. Within the church, questions come up: how are you going to have communion? How are we gonna baptize? What are you gonna teach the new convert? Questions have to be answered. And so you begin a tradition. It’s the social glue that brings cohesiveness to a clan or a tribe.

In order for any group to retain its identity for more than one generation, they have to articulate their reason for existence to the next generation. And no group can do that effectively by merely saying, “we’re Christians. Mere Christians,” because there are thousands upon thousands of such groups, and the questions always remains: “well, what’s your group’s reason for existing, and not joining up with another?” And so I kept asking that question at Shalom: “why don’t we go down to the first church down the street?” And eventually about half of ’em did [laughter]. It was after I resigned that they ended up doing it.

Tradition forms the backdrop of particular doctrines, and if you lose the tradition, you end up losing the doctrine. If you lose the tradition that led up to this statement that “Jesus was God in human flesh” (and part of the tradition was the battle which was fought), then you lose the meaningfulness of the doctrine. It ceases to be significant. You have to be self-confident about your roots, otherwise you’ll be tossed to and fro by the winds of modernity. So as a pastor, then, I had to come to grips with this question of tradition, both sociologically and theologically. It was clear to me from reading the Apostle Paul’s letters, that he believed in an unwritten tradition that he was passing along to his people. He referred to what he had passed on that he had heard from other witnesses. And he expected that to be binding. So the question wasn’t whether there would be tradition or not. There would be. The question was: by what authority do you determine right tradition from wrong tradition?

I guess the coup de gras for me on this issue of tradition was the realization that evangelical Protestantism has tradition right at its core. The canon of Scripture is itself a tradition nowhere established in the Bible. It’s a church tradition. Francis Schaeffer was very good in that he taught me that one’s presuppositions and first principles must be able to be lived and not just thought. And yet Protestantism cannot live out faithfully its commitment to the Bible alone, because on that basis there’d be no canon of Scripture. There’d be no Bible!

So Protestants are in the terrible position of having its primary authority not being able to justify its own existence. They have to justify a collection of books, which are secondary to the Word. The Word is prior to the community. The Word calls forth the community, and the community gathers around that Word. The process of inscripturation is subsequent. It comes as the community reflects upon the Word, and is used to crystallize and condense that Word for posterity. Jesus Himself functioned as the Word, which drew a community together, which then produced certain documents and collected them.

Another thing that hit me as a pastor was the nature of the Church and Church government. Francis Schaeffer had taught me back in 1974, in his book, The Mark of a Christian, that in John 13 and 17, Jesus talks about a real, visible oneness, a practicing, practical oneness, across all denominational lines, among all Christians. We cannot expect the world to believe that the Father sent the Son, and to believe that Jesus’s claims are true, and that Christianity is true, unless the world sees some reality of the oneness of true Christians. He kept talking about oneness in terms of people getting along with one another. He did not like the Roman Catholic Church at all. He thought it was an enforced uniformity and he complained about conservatives and progressives squabbling miserably in the Roman Catholic Church. But what he did do for me was focus on “visible.” It had to be visible. This unity had to be observable by the unbelieving world.

[recalls the story of an erring, unrepentant, sinning brother in his congregation, who left when confronted] How can you exercise restorative church discipline, if all they do is bump off to another church? So all of a sudden institutions became not a bad thing, but a good thing. If we were part of a denomination we probably could do something. But then again he could just go to another denomination. So I began thinking about issues of excommunication, by what authority do you excommunicate; what are the guidelines for it? And it dawned on me that the New Tesdtament never expected a situation where, if you were barred from the fellowship, that you could just go over to some other fellowship! The Apostle Paul in 1 Corinthians 5, says “I’m gonna turn this fellow over to Satan for the salvation of his soul,” and in 2 Corinthians, he has to say, “listen, back off this guy! You’ve disciplined him enough; he’s at the point of despair. Welcome him back as a brother.”

That was a major turning point, because my pastoral work was jeopardized by the existence of competing fellowships. This really disturbed me, in a way that’s hard to describe to people who haven’t been in that [situation], but my pastoral effort was now cheapened. How can you discipline if there’s no unity of the body? Even in the New Testament, with all the disagreements among believers about law and grace and circumcision and eating of meat offered to idols, and qualifications for leadership, splintering into independent groups is never advocated. In fact, one of the few offenses that give us reason to separate from a brother is the offense of disunity (Romans 16): “I urge you brothers, to watch out for those who cause divisions. Keep away from them.” So I was big on this church unity thing, but it was all invisible, spiritual, all out here. And it wasn’t working very well.

I’d also taught on 1 Timothy 3:15: “the church is the pillar and foundation of the truth.” It was one of those sermons where I would say, “and that’s us!” And I’d look out there and I’d say, “like hell it is!” This is a joke! Here we are, 125 of us: “the pillar and foundation of the truth.” And Paul wasn’t referring to some invisible reality.

I think the thing that brought me through the home stretch was teaching through the book of Romans. In the Protestant tradition, Romans is the book par excellence on justification by faith alone. This provided my undoing. Finally, I’m into the text that evangelicals and Protestant love the most, and I find that the distinctive doctrines of the Reformation are not taught there. They’re just not there. I found that Paul’s disgust with works of the law is not a disgust with human striving to please God, but with the Jewish community’s vain imagination that because they performed the works of the law, the practices that keep them distinct from the Gentiles, that they have special status with God. As I taught on justification, I saw that Paul did think that justification by grace through faith changes a person’s life. All these arcane arguments out of the Reformation about extrinsic justification were only so much hooey. The Apostle Paul would have said, “this is a waste of time, guys. This is not the point.” In 1 Corinthians chapter 6, justification and sanctification are linked together . . . God doesn’t merely impute righteousness to you, but He does something in the soul to make you righteous.

Paul also expected the obedience of faith. It’s as though faith is the response of trust, in the same way that obedience is the response of the will. Here you’ve got a gospel which is quite different than the gospel that is commonly preached. This was disturbing to me. I began to say to myself, “if I don’t believe in the doctrine of justification by faith alone, where am I gonna go?” I didn’t really think of myself going into Catholicism at all. I thought, maybe Eastern Orthodoxy. This was around 1988, 1989.

Another thing I learned while teaching through Romans was the inescapability of suffering if we are to share in His inheritance and glory. There was something about it in Romans 8 where the Apostle Paul actually links suffering; you must suffer . . . it seemed so contrary to, other than, the gospel I was used to hearing preached. Most of the gospel preaching you hear is, “come to Jesus because He will fulfill you; you’ll receive some benefit.” It’s true, you do receive some benefit, so I don’t despise all of that. But there’s something wrong when the call to Jesus is not also accompanied with a call to suffer with Him. It’s as if you’re called to the resurrected Christ, but not the suffering Christ; as if people are given the crown without the cross. That struck me because I knew Catholics were big into crucifixes, and I said to myself, “they probably have some insight on this.”

And a Catholic friend of mine emphasized Colossians where Paul talks about “making up in his body that which was lacking in Christ’s afflictions,” and I thought, “now that makes sense of this teaching in Romans 8. Crucifixes make sense.” It’s as though people have to be reminded that there’s no crown without the cross. Our baptism into Jesus is a baptism into His death. Christ’s work is quite complete, but the application of it has to go on in the world, and so it’s in that sense that we share His suffering because we are members of His body, applying the work of redemption which He wrought for us on Calvary.

Thirdly, I became aware that the apostles believed in sacraments of some sort; undeveloped, I think. But definitely there was a sacramental awareness. The baptism referred to in Romans 6 really is wet. In the mind of the apostles, water and spirit were not separate entities. The images go together: baptized by water and spirit, the washing of regeneration in Titus. And I began to think more and more about this: where do you find unbaptized Christians in the New Testament? You don’t. Then I began making a list of what Paul says about baptism and faith. And I found out that the same things that are being said about faith are also being said about baptism. I came to the conclusion that in some mysterious way, they believed that when a person was baptized, there was some change that happened. I was convinced that it was far more than just a symbol.

The same thing happened with the Eucharist, when I taught about that, later on. I began to feel that I was just playing church, whenever we had the Lord’s Table. It seemed so clear to me from 1 Corinthians 11, Luke 24, that Jesus was present in some real way in the Lord’s Table. I knew that I could no longer participate, or preside over the Lord’s Table.

Operation Rescue was another major turning point for me, because it exposed the papal pretensions of many evangelical leaders. When I saw the obvious biblical justification for Operation Rescue, and yet the resistance it got from major evangelical leaders, I said to myself, “there’s really no hope for this community. In fact, it isn’t a community; it’s a bunch of disparate fiefdoms, kingdoms that these people have built. These are sheep without a shepherd. There’s nobody here that can bring this together.” If an issue like abortion cannot bring the community together, in this way, and if civil disobedience of this sort . . . if people like Norman Geisler and Bill Gothard can’t simply let their brothers and sisters go about this work (they may think it’s foolish, unwise, or that pragmatically it’s not gonna work), but let ’em do it. Don’t try to argue from the Bible against Operation Rescue, because you can’t do it. It’s an impossible job.

Norm Geisler was on my show. A question was posed to Geisler [by another guest]: “are you telling me that if there were four-year-olds being slaughtered at governmentally-approved slaughter clinics, that you wouldn’t trespass in order to save one of those four-year-old’s lives?” He said “I would only do it if it was my kid.” It was pathetic. I couldn’t believe he said it. It was a reductio ad absurdum. And then I read Bill Gothard’s material against Operation Rescue and it was sinful, it was a caricature of the position, and a twisting of Scripture like I’ve rarely seen from a major evangelical leader; and I had read papal statements, too, not on Operation Rescue, but on civil disobedience, and I knew there was a rich tradition in the Roman Catholic Church, dealing with social crises of this form, and what a conscientious conscience should do.

Operation Rescue was one of the final nails in the coffin of my evangelical experience. I was so terribly disillusioned by the response. I just couldn’t believe it. I think you can construct a good argument against Operation Rescue, but not from the Scripture; rather, on pragmatic grounds. These guys wouldn’t do that; they wanted to argue from the Scripture on it, and I said “there’s no hope.” That was a turning point for me. I could go on; many other reasons.

So I resigned [the pastorate] in December of 1990. I had wanted to a year before, but I had commitments. The church wasn’t ready. These were good people. I didn’t want to enter into battle. I didn’t know where I was going, and I knew I wasn’t fit to be a pastor, because you don’t need the blind leading the blind. I shared with them about the Real Presence because by that time it was no longer speculative for me. I was thoroughly convinced on biblical authority. I told people that I was tired, fatigued. I had been working full-time at WMUZ [radio station; his talk show] and the church for over a year. I told them that I was thinking of becoming Catholic or Eastern Orthodox. I couldn’t really stay at the church. I just felt bad. If you don’t know where you’re going, you shouldn’t be taking people with you. I was on my own journey. I wasn’t fit to lead them on it. So I keft the church and began pursuing Catholicism and Orthodoxy.

During the previous year, I’d had Fr. Peter Stravinskas on [the radio show], and during the course of some of his discussion, as he was describing the Mass as a re-presentation of Christ, I recognized the doctrine that I held in a diluted form. It was a doctrine that I used to call “memorial consciousness.” I used to teach that at Shalom: that past saving events could be re-presented in the present. The Jews tried to do it with Passover. The same thing with the Lord’s Supper. So when Fr. Peter said that, I had this rush of adrenaline while I was on the air, and I said to myself, “my God, I’m a Catholic” [understanding laughter in the room].

I was still pastoring at Shalom at the time. It was an exhilarating experience but disturbing at the same time. It was as though I had been walking in the dark for a long time and getting along pretty well, and then all of a sudden the light gets turned on, and you realize that you’re perched on a tightrope about 100 feet above the ground. You were doing fine, as long as you didn’t know where you were. But here you are: mid-way out, and on the one hand, you can take heart that you made it so far, but on the other hand, you’re trembling because you can see how far you gotta go, and you’re not quite certain you’re gonna get to the other side.

So I had this subjective experience, and yet I hadn’t really settled the Marian dogmas, or a lot of things, and I honestly didn’t like most of the Catholics I’ve met. Now you guys are pretty good; I like you [great laughter], . . . once I left Shalom I began going to Masses at various places. I’d read on a Saturday books on Catholicism and Orthodoxy and sacramental thinking. Then I’d go to Mass, and every time I’d think I was ready to come back in, based on my study, all I’d have to do was go to Mass to get cold water thrown on me: thoroughly disillusioning. Part of that was that I wasn’t connected to a community . . . it wasn’t a happy time because I was really feeling left in the lurch; intellectually persuaded of many things, but not any community life at all.

So I kept getting these Catholics on the air and debating. I thought it was good programming, too. I had Karl Keating on once debating Harold O. J. Brown. And I remember, Karl was good, but I was much more impressed with Harold: at how non-victorious his Protestant arguments were. I really thought that he’d be able to push Karl around a little bit, but he couldn’t. Karl made some great points. Then I had Fr. Peter Stravinskas on, on Reformation Day, to talk about the Reformation with this Church history professor from Dallas Seminary, and again I was impressed with Fr. Peter, but I was very impressed at how the Dallas prof really couldn’t justify the Reformation. When all was said and done, that guy had no reason to be a Protestant. He agreed with Fr. Peter that the real reasons for the Reformation were not theological, they were economical and political [he chuckles] . . .

Another major turning point was when I came across Matthew 16. I knew the Protestant arguments, and I had taught them myself. To be honest with you, I really thought that the Catholic argument was a justification of the status quo. I thought it was a rationalization of the papal office. I didn’t think it was exegetically sound at all. There was such unanimity. All the preachers I’d ever heard on Matthew 16 said that the rock was Peter’s faith, or it was a play on words, and I just assumed that. And I figured that evangelicals are known for exegesis; Catholics aren’t, so evangelicals are probably right on this.

So I went and picked up two commentaries in my library, by two noted evangelical New Testament scholars: Donald [D. A.] Carson, who is among the top ten brightest people I’d ever had on the air, and another fellow, R. T. France, whom I know is an excellent exegete. And I brought them up to my bed. And both of them, the same night (before I had ever heard Scott Hahn tapes); I read Carson, and he wrote “had it not been for Protestant overreaction to exaggerated papal claims, virtually nobody would have ever thought that the rock referred to Peter’s faith. It’s clearly a reference to Peter.” And I said, “I’ve never heard that before!” Then I went over to R. T. France, and I read that, and I said, “is he quoting Carson?” He said virtually the same thing! And I was stunned. And I began to make some phone calls, and I found out that in New Testament scholarship, this is becoming the consensus position! Peter is the rock, not Peter’s confession. It’s straightforward.

The Marian dogmas were big problems. I still thought [around 1984] the Catholic claims on Mary were outrageous. I went back and read some essays, and concluded that the Bible alone wouldn’t compel acceptance of the Marian dogmas; the Bible alone wouldn’t lead you to them, yet sustained theological reflection on Jesus’ relationship to His mother; if you take the humanity of Jesus with the utmost seriousness, and you take Mary as a real mother, not just a “conduit,” and you begin to think about motherhood and sonship, and you think about what it means to receive a body from your mother: flesh . . . God didn’t make Jesus’ flesh in Mary’s womb; He got Mary’s flesh. If God had wanted to, He could have made Jesus as He made Adam: from the dust of the earth. But He didn’t. He decided He would use a human being to give Jesus His humanity.

And so what kind of flesh is Jesus gonna get? If He’s gonna be perfect humanity, He’d better have perfect human flesh untainted by sin. To me the Immaculate Conception, seen in that light, made sense. The Assumption also seemed to me to make a great deal of sense. There were precedents to it: Enoch and Elijah, those who rose from the dead at the time of the rending of the veil of the Temple. And if Jesus is going to give anybodye priority; if He’s going to truly honor His mother and father, wouldn’t He give Mary, whose flesh He received, priority in the Resurrection? So I think that’s what the doctrine of the Assumption preserves. I could go on and talk forever on the distinctive doctrines of the Church.

Artificial contraception . . . Dave wanted me to go into that [I had asked a question earlier]. I had a very difficult time seeing it as good logic. The Church insists that the multiple meanings of sexual intercourse always be exercised together. Since one of the meanings is procreation and another is intimacy or the what’s called the “unitive function”, those things can’t be separated from one another licitly. I didn’t like that, because it seemed to me that if intercourse served multiple purposes, then there’s no reason why, at any particular time, one purpose ought to retain priority or even exclusivity in the exercise of that act. They were both good.

I think that the change came when I finally hit upon an analogy; I had to see another human act in which multiple meanings had to be exercised together, and not separately. And I thought of eating food. Food serves multiple purposes: nutrition, secondly, pleasing our senses. God likes tastes; that’s why He gave us taste buds. He wants food to taste good. What do we think of a person who says, “I really like the taste of food, so I’m going to disconnect my eating of food from nutrition, and I’m just gonna taste it.” Well, we call him a glutton; we call him a “junk food junkie.” What do we call a person who says, “I don’t care about what food tastes like; I’m just gonna eat for nutrition’s sake.” We call him a prude or we have some other name for him. We think that they’re lacking in their humanity. That helped me in understanding sexual intercourse.

I think it’s sinful just to eat for the taste, or merely for the nutrition, because you’re denying the pleasure that God intended for you to receive, in eating good food. I say the same thing with sexual intercourse. You’re sinful if you separate the multiple meanings of it. If you procreate simply to make babies, and you don’t enjoy the other person as a person, I think that’s sinful, and I think that if you merely enjoy sexual intimacy and pleasure, and are not open to sharing that with a third life: a potential child, then you’re denying the meaning of sexual expression. That was a continuing realization that the Catholic Church had been there before me.

When I learned that you [referring to me] were interested in the Catholic Church, it was kind of funny, because by that time I had been pursuing this on my own, and feeling like I was a little bit odd. So it was good for me, . . . I was their pastor for a while at Shalom, and Dave and Judy and Sally and I have known each other for many years, and I’ve always liked Dave and Judy. We’ve had some disagreements at times over the years, and a little bit of even, “combat,” but I always was fond of them, because I always recognized them as people who were willing to live out their convictions, and that always means a lot to me.

I like to be surrounded by people like that because it’s very easy to just live in your head and not get it out onto your feet. So I knew that they were committed to living a Christian life. They were interested in simple living, and interested in alternate lifestyle. They saw themselves as being radical Christians. And I always liked that. So even when we disagreed, I was always fond of them, in that I respected what they were doing. So it was heartening to me, to find that my return to the Church was in its own way being paralleled by Dave’s acceptance of Roman Catholicism. It was a queer parallelism. When we went to see Fr. John Hardon that night, I thought it was interesting and odd that you were doing it, but I told you that night: “it seems to me there are only two choices: either Orthodoxy or Catholicism.” It was reassuring. I met Catholics through rescue that I actually liked, and that was heartening.

I returned to the Catholic Church, because, for all its shortcomings (which are obvious to many evangelicals), both evangelicalism and Catholicism suffered from the same kind of “immoral equivalency.” All the things that I once thought were uniquely bad about Catholicism, I also saw in Protestantism, so it was kind of a wash. I stopped asking myself all the so-called practical questions, and made the decision based on theology alone. That way I got to compare theology with theology. People love to compare the practice of one group with the theology of another. So you end up with the theology of a John Calvin versus the practice of some babushka’d Catholic woman. And it’s just not fair. You gotta compare apples with apples. Evangelicals tolerate pentecostal superstition and fundamentalist ignorance, without breaking fellowship. So why criticize the Catholics for tolerating some superstition and ignorance?

Evangelical churches are largely made up of small, dead, ineffectual fellowships. Two-, three-generation fellowships that have lost their reason for existence, and they just keep rollin’ along. The vast percentage of evangelical churches are about 75 people. And they’re not doin’ much. So what’s the problem if Catholic churches are full of dead people too? It’s a wash. Evangelicals tolerate and even respond positively to papal figures like Bill Gothard, Jimmy Swaggart, Pat Robertson, and men whose teachings or decisions explicitly or implicitly sets the tone of the discussion and suggests and insists upon right conclusions.

And these men are not just popular leaders, they are populist leaders. In other words, they often appeal to the anti-intellectual side of the uneducated. They stir up resentments between factions in the Church Politic and the Body Politic. The pope, on the other hand, is not a populist leader. You don’t see the pope, in the encyclicals I’ve read, taking cheap shots, driving wedges between the intelligentsia and the masses; you don’t see them doing cheap rhetorical tricks, like you do find among popular evangelical leaders. If the pope plays his audience, it’s usually through acts of piety. He’s not trying to stir up resentments.

Evangelicals are currently seeking more sense of community and international community, more accountability — you hear more talk about confessing your sins to one another; they’re looking for a way to justify the canon, visible signs of unity. Catholicism has all these things. It offers them already. And then of course evangelicals seem only to be able to preserve doctrinal purity by separating, dividing, and splitting and rupturing the unity of Christ. That’s their method for maintaining the truth: divide. And that to me is the devil’s tactic: “go ahead, divide ’em; it’s easier to conquer them that way.”

Even in the area of their strength (the Bible), evangelicals are not without serious shortcomings. Matthew 16 is a great example of that. What’s worse?: to omit clear biblical teaching, or to add to it? Evangelicals omit fundamental biblical teaching about Peter as the rock, about the apostolic privilege of forgiving or retaining sins. These things are not unclear. They’re only unclear in the Scripture if you’ve adopted a certain type of theology, and then you have to dance around, doing hermeneutical gymnastics to avoid the clear intention of the verse. The binding and loosing passages in Matthew 16 and 18 are as plain as the nose on your face.

So I returned to the Catholic Church because I am absolutely convinced that the Roman Catholic Church preserves and retains (for all its shortcomings) the biblical shape of reality. It retains sacramental awareness, human mediation (which is a very prominent biblical theme which has been lost in evangelical churches), a sense of the sacred, which is present in the Scripture; and recognizes typology as having not only symbolic value, or pedagogical value, but also ontological value. It retains memorial consciousness and corporate personality, the idea of federal headship, doctrinal development. All of these things are lectures in and of themselves. But these things that people always wanna talk about (purgatory, saints, Mary), all fit into those categories. The structure of biblical reality is more present in Catholicism than any other tradition that I’m familiar with. And I’m really quite convinced that I don’t have extravagant expectations, either. I think these things are really there. It’s not a pipe dream.

[someone asked, “why not Orthodoxy?”]

Competing jurisdictions, which basically told me, “you need a pope.” If the point is that you need a visible display of unity for the work of evangelism to have lasting success, how can you have the Russians and the Greeks fighting with one another all the time? I know conservatives and liberals fight in the Catholic Church, but it’s structured in such a way as to be able to end the debate at some point. God acts infallibly through the papacy. The discussion can be settled. It can’t be settled in Orthodoxy at this point. They’re always fighting over jurisdictions. The laxity on divorce . . . I heard a saying recently that “your doctrine of ecclesiology will affect your doctrine of marriage, or vice versa.”

If you believe in divorce, then you believe in the Reformation, because you believe that Christ will divorce part of His Body. If you believe that the relationship between Christ and His bride, the Church, is indivisible, then you will believe that (among Christians, anyway) marriage is indivisible. There should be no divorce. And I think that the Orthodox are lax in that area. I think that they’re too ethnic – that’s probably due to a type of caesaropapism, and that their views of culture don’t seem to work out very well. Those are some of the reasons. Also, it just wasn’t around. Where do you go? You have to work too hard to find a place, and then you have to worry about whether they’ll do it in English. I went to St. Suzanne’s first of all because it was around the corner, and I believe that geography has a lot to do with community.

[I asked, “what was the very last thing that put you over the edge?”]

It was very incremental. Instead of their being one moment of decisive realization, there were moments of little pinpricks of light along the way. In one sense I crossed the line when I heard Fr. Stravinskas describing the Mass as a re-presentation of Christ’s sacrifice, and I realized that the worldview that he was presenting was the worldview that I had believed for a long time, but had not been able to articulate. But I didn’t know where to go from there. I think it was the same day that that happened, the one man who had been most influential on my thinking on the relationship between religion and culture during the 1980s, Richard John Neuhaus, announced that he had become a Catholic. I said, “oh my God!” His book, The Naked Public Square, really shaped my thinking on the relationship between religion and public life.

And another one would be the Scott Hahn tapes on Mary. What Scott did for me was, he managed to draw enough suggestive biblical material, that my ideas of development now could be fed from the Scripture. You have to understand that the Marian dogmas just seemed excessive. It’s not that I had any intrinsic hostility to them. I thought they were kind of nice in their own way. But I didn’t see the biblical precedent to it. He gave me enough biblical material to ignite a spark of hope about them, and then when I began reading the theology on them, I said, “I can receive this now.” We’re talking months.

I remember now: I needed reassurance. I’d forgotten all about this. What was on my mind was the work of the kingdom, and whether I could be as effective within the Catholic Church, as I could be in the Protestant church. I hadn’t nailed down everything about Catholicism, but I recognized that the shape of Catholicism was a lot closer to the Bible, than a lot of what I was seeing in Protestantism. But practically speaking, you don’t see Catholic evangelists out there very much. It came down to this: what justified staying apart? “What reason do I have for not being there?”