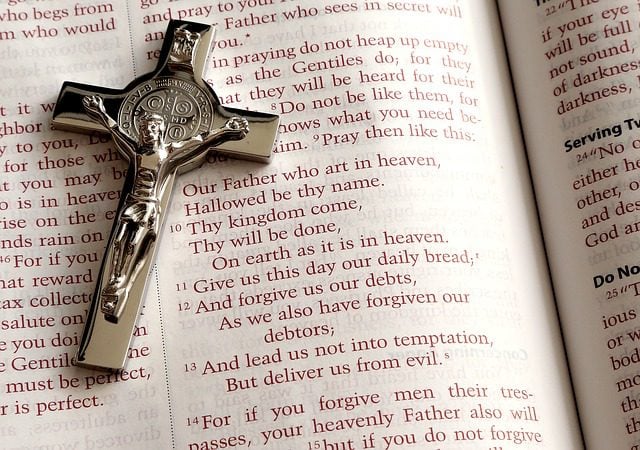

Photograph by “jclk8888” (7-7-13) [Pixabay / CC0 public domain]

*****

Matthew 12:31-32 (RSV) Therefore I tell you, every sin and blasphemy will be forgiven men, but the blasphemy against the Spirit will not be forgiven. [32] And whoever says a word against the Son of man will be forgiven; but whoever speaks against the Holy Spirit will not be forgiven, either in this age or in the age to come.

St. Augustine (354-430): For some of the dead, indeed, the prayer of the Church or of pious individuals is heard; but it is for those who, having been regenerated in Christ, did not spend their life so wickedly that they can be judged unworthy of such compassion, nor so well that they can be considered to have no need of it. As also, after the resurrection, there will be some of the dead to whom, after they have endured the pains proper to the spirits of the dead, mercy shall be accorded, and acquittal from the punishment of the eternal fire. For were there not some whose sins, though not remitted in this life, shall be remitted in that which is to come, it could not be truly said,They shall not be forgiven, neither in this world, neither in that which is to come.(City of God, Book 21, chapter 24)

Pope St. Gregory the Great (c. 540-604): But yet we must believe that before the day of judgment there is a Purgatory fire for certain small sins: because our Saviour saith, that he which speaketh blasphemy against the holy Ghost, that it shall not be forgiven him, neither in this world, nor in the world to come. Out of which sentence we learn, that some sins are forgiven in this world, and some other may be pardoned in the next: for that which is denied concerning one sin, is consequently understood to be granted touching some other. (Dialogues, Book IV, chapter 39)

St. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153): They do not believe that there remains after death the fire of purgatory, but allege that when the soul is released from the body it passes straight to rest or to damnation. Let them ask of him who said that there was a sin which should not be forgiven in this world nor in the world to come. (“These New Heretics”; Sermon 66 on the Song of Songs)

The Venerable Bede (c. 672-735) took the same position (Commentary on Mark 3)

How can the denial that this sin will . . . ever be forgiven, even after death, be the basis for speculating that sins will be forgiven in the next life?

*

I reply that mentioning “the age to come” obviously assumes the premise that such things can happen in the afterlife; after death. Otherwise, why mention it? We don’t include in our observations what we regard as a falsehood or impossible. No one would say, for example, “a circle is round and also is square.” The first thing is obviously true, and the second is categorically impossible.

If Jesus thought (like Protestants) that there is no forgiveness (or purgatory) after death (as a similar categorical impossibility), then He would have never mentioned even its theoretical potentiality. He simply wouldn’t bring it up at all. He doesn’t teach falsehood, being God and omniscient. The final clause wouldn’t be in the text. But there it is!

The “polemical structure” of the Catholic argument in this instance is similar to the biblical argument for praying to someone other than God, found in Luke 16 (remarkably unnoticed by Protestants who, again, deny a thing that Jesus plainly asserts). I explored that in another article of mine:

[Luke] 16:24 (RSV): “And he called out, ‘Father Abraham, have mercy upon me, and send Laz’arus to dip the end of his finger in water and cool my tongue; for I am in anguish in this flame.’ ”

Abraham says no (16:25-26), just as God will say no to a prayer not according to His will. He asks him again, begging (16:27-28).

Abraham refuses again, saying (16:29): “They have Moses and the prophets; let them hear them.’” He asks a third time (16:30), and Abraham refuses again, reiterating the reason why (16:31).

. . . If we were not supposed to ask saints to pray for us, I think this story would be almost the very last way to make that supposed point.

Abraham would simply have said, “you shouldn’t be asking me for anything; ask God!” In the same way, analogously, angels refuse worship when it is offered, because only God can be worshiped [I cited Rev 19:9-10; 22:89]. St. Peter did the same thing [Acts 10:25-26]. So did St. Paul and Barnabas [Acts 14:11-15].

If the true theology is that Abraham cannot be asked an intercessory request, then Abraham would have noted this and refused to even hear it. But instead he heard the request [three times!] and said no.

Jesus couldn’t possibly have taught a false principle.

Likewise (following the analogy above to the argument about prayer), if there is no such thing as forgiveness “in the age to come” Jesus would not have alluded to it. The fact that one sin can’t be forgiven even in the next life does not prove that none can be forgiven, just as Abraham’s (not God’s!) refusal to grant one prayer does not prove that no one can pray to anyone other than God. It proves, rather, that not all prayers (including prayers offered to saints or angels) are answered as the one praying would like them to be answered. God or the saint or angel may refuse the petition.

Ironically, on page 339, Geisler (in the midst of a different argument against purgatory), refers to the rich man praying to Abraham (he uses the description, “cried out”). Moreover, he agrees (footnote 26) with my contention that this passage is not a parable:

Even if it were [a parable], it still describes some actual reality. Furthermore, nowhere is this called a parable, nor do parables ever use real names in them like “Lazarus” and “Abraham.”

Geisler even admits that this is indeed a prayer, but he states (in a different context on p. 350), that:

[T]he only prayer in the Bible addressed to a saint was from hell, and God did not answer it (Luke 16:23-31). [italics his own]

I already replied above to the irrelevancy of saying that the prayer wasn’t answered, within the context of the overall argument. Secondly, this is Hades, or Sheol: the “netherworld”, which is a different thing from hell. This isn’t speculation. The text itself states that it is “Hades” (16:23). Surely, Geisler, being a theologian, knows the difference between Hades and hell (which is usually from the Greek, Gehenna in the New Testament). Hades is even contrasted with “the lake of fire” (which is hell) in one passage (Rev 20:14).

But in his zeal for refuting a Catholic argument, Geisler inadvertently backs into defending purgatory (in a vague sense) by the logical implication or reduction of his argument, since he in effect acknowledges (whether he is aware of it or not!) that there is at least one “third state” after death besides heaven and hell (Hades / Sheol). If one denies all third states altogether, that would include purgatory. But if one concedes that there can be a third state, then purgatory is at least possible and cannot be ruled out a priori.

Geisler then argues (p. 335):

[T]he passage is not even speaking about punishment, which Catholics argue will occur in purgatory. So how could this text be used to support the concept of purgatorial punishment?

But this is not the Catholic argument in the first place; it is, rather, that forgiveness of sins after death is one essential aspect of purgatory, which this passage supports. It’s a partial proof of purgatory, not a full one (every particular aspect of purgatory). But it is taking the reader to “waters” that are strange for Protestants: very murky and over their heads.

He continues (p. 335) to miss the main point:

[P]urgatory involves only venial sins, but this sin . . . is mortal, being eternal and unforgivable . . . even if this passage did imply punishment, it is not for those who will eventually be saved . . . but for those who never will be saved . . . It only indicates the lack of real biblical support for the doctrine.

Remarkably enough (for such a generally good debater), he never engages the argument (explained above) as actually used by Catholics. Geisler totally fails to refute the Catholic argument, derived from one as great as St. Augustine (much beloved by Protestants), since all he did was flail away after straw men and cardboard caricatures the whole time.