Now the gift of grace surpasses every capability of created nature, since it is nothing short of a partaking of the Divine Nature, which exceeds every other nature. And thus it is impossible that any creature should cause grace. For it is as necessary that God alone should deify, bestowing a partaking of the Divine Nature by a participated likeness, as it is impossible that anything save fire should enkindle.

(Summa Theologica, First Part of the Second Part, Q. 112: The Cause of Grace, Art. 1: Whether God Alone is the Cause of Grace)

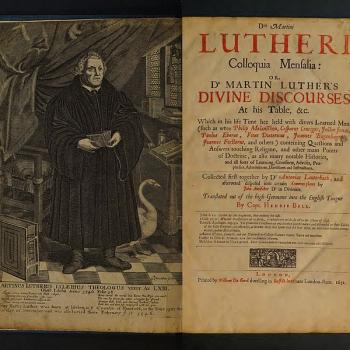

The following information was obtained from the fascinating article, “Luther and Theosis,” by Kurt E. Marquart, Associate Professor of Systematic Theology at Concordia Theological Seminary (Fort Wayne, Indiana), and was published in Concordia Theological Quarterly, Vol. 64:3, July 200, pp. 182-205.

Many back issues of that excellent scholarly magazine are available online on a great site that I happily ran across. All subsequent words below are from the article, with Luther’s own words in blue. Footnotes appear in brackets immediately after the section that utilizes the sources therein.

The most celebrated patristic statement on the subject is no doubt that of Athanasius: “For He was made man that we might be made God.” To avoid any pantheistic misunderstandings, it is necessary to see that “deification” applies first of all to the flesh of the incarnate Son of God Himself. It is simply a traditional way of putting what Lutherans now call the second genus, or the genus maiestaticum, of the communication of attributes.

[ . . . ]

In a 1526 sermon Luther said: “God pours out Christ His dear Son over us and pours Himself into us and draws us into Himself, so that He becomes completely humanified (vermzenschet) and we become completely deified (gantz und gar vergottet, “Godded-through”) and everything is altogether one thing, God, Christ, and you.”‘

[Martin Luther, D. Martin Luthers Werke. Kritische Gesamtausgabe, 58 volumes (Weimar, 1883- ), 20:229,30 and following, cited in Werner Elert, The Structure of Lutheranism, volume 1 (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1962),175-176. The present author has altered the translation given there in order to make it more literal. All subsequent references to the Weimar edition of Luther’s works will be abbreviated WA.]

[ . . . ]

Sadly, this we] is now unknown in the whole world, and is neither preached nor pursued; indeed, we are even quite ignorant of our own name, why we are Christians and are so-called. Surely we are so-called not from Christ absent, but from Christ dwelling [inhabitante] in us, that is, inasmuch as we believe in Him and are mutually one another’s Christ, doing for neighbors just as Christ does for us.

We conclude therefore that the Christian lives not in himself, but in Christ and in his neighbor, or he is no Christian; in Christ through faith, in the neighbor through love. Through faith he is rapt above himself into God, and by love he in turn flows beneath himself into the neighbor, remaining always in God and in His love.

[The Freedom of the Christian, Latin: WA 7:66,69; German: WA 7:35-36,38; English: Luther’s Works, American Edition, 55 volumes, edited by J. Pelikan and H. T. Lehmann (Saint Louis: Concordia and Philadelphia: Fortress, 1955-1986), 31:368, 371. In “Theosis as a Subject,” the end of the first paragraph has been rendered “mutually in one another, another and different Christ. . .” Subsequent references to the American edition of Luther’s works will be abbreviated LW.]

In an early (1515) Christmas sermon, Luther notes:

As the Word became flesh, so it is certainly necessary that the flesh should also become Word. For just for this reason does the Word become flesh, in order that the flesh might become Word. In other words: God becomes man, in order that man should become God. Thus strength becomes weak in order that weakness might become strong. The Logos puts on our form and figure and image and likeness, in order that He might clothe us with His image, form, likeness. Thus wisdom becomes foolish, in order that foolishness might become wisdom, and so in all other things which are in God and us, in all of which He assumes ours in order to confer upon us

His [things].We who are flesh are made Word not by being substantially changed into the Word, but by taking it on [assumimus] and uniting it to ourselves by faith, on account of which union we are said not only to have but even to be the Word.”

[WA 1 2825-3239-41. Cited in “Grundlagenforschun,” 192; “Zwei Arten,” 163.]

[ . . . ]

The one who has faith is a completely divine man [plane est divinus homo], a son of God, the inheritor of the universe. . . . Therefore the Abraham who has faith fills heaven and earth; thus every Christian fills heaven and earth by his faith. . .

[WA 40 I:182,390; LW 26:1001 247,248.]

Obviously there are many implications here as well for love, good works, and other important topics . . .

[ . . . ]

. . . Luther . . . knows a God who is not gingerly beaming thoughts and effects at us from afar while taking care to keep His real being (if He has any!) well away from us. With Luther biblical realism is in full cry:

The fanatical spirits today speak about faith in Christ in the manner of the sophists. They imagine that faith is a quality that clings to the heart apart from Christ [excluso Christo]. This is a dangerous error. Christ should be set forth in such a way that apart from Him you see nothing at all and that you believe that nothing is nearer and closer to you than He. For He is not sitting idle in heaven but is completely present [praesentissimus] with us, active and living in us as chapter two says (2:20): “It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me,” and here: “You have put on Christ. . . .”

Hence the speculation of the sectarians is vain when they imagine that Christ is present in us “spiritually,” that is, speculatively, but is present really in heaven. Christ and faith must be completely joined. We must simply take our place in heaven; and Christ must be, live, and work in us. But He lives and works in us, not speculatively but really, with presence and with power [realiter, praesentissime et eficacissim].

[WA 40 1:545-546; LW 26:356-357; “In ipsa,” 39-40.]

By faith, finally,

you are so cemented [conglutineris] to Christ that He and you are as one person, which cannot be separated but remains attached [perpetuo adhaerescat] to Him forever and declares: “I am as Christ.” And Christ, in turn, says: “I am as that sinner who is attached to Me, and I to him. For by faith we are joined together into one flesh and one bone.” Thus Ephesians 5:30 says: “We are members of the body of Christ, of His flesh and of His bones,” in such a way that this faith couples Christ and me more intimately than a husband is coupled to his wife.

[WA 40 1:285-286; LW 26:l68; “In ipsa,” 51.]

[ . . . ]

And that we are so filled with “all the fulness of God,” that is said in the Hebrew manner, meaning that we are filled in every way in which He fills, and become full of God, showered with all gifts and grace and filled with His Spirit, Who is to make us bold, and enlighten us with His light, and live His life in us, that His bliss make us blest, His love awaken love in us. In short, that everything that He is and can do, be fully in us and mightily work, that we be completely deified [vergottet], not that we have a particle or only some pieces of God, but all fulness. Much has been written about how man should be deified; there they made ladders, on which one should climb into heaven, and much of that sort of thing. Yet it is sheer piecemeal effort; but here [in faith] the right and closest way to get there is indicated, that you become full of God, that you lack in no thing, but have everything in one heap, that everything that you speak, think, walk, in sum, your whole life be completely divine [Gottisch].

[Sermon of 1525, WA 17 1:438; “In ipsa,” 54.]

When one ponders the lively, full-blooded realism of Luther’s theology, one can only wonder how such a legacy could have been so tragically squandered in world “Lutheranism” over the centuries. Chesterton complained about the Church of England’s tendency to tolerate “underbelievers” but to persecute “overbelievers.” Why this preference for ever less, for the minimal? Reductionist philosophy alone is hardly the whole story. Sin has a way of defending itself against God’s saving incursions on a broad front.

[ . . . ]

If there is such a thing as a characteristic “structure of Lutheranism” which distinguishes it from other confessions, then it must lie surely in a relentless realism of faith that will not let any of God’s life-bearing gifts be spirited away into significances and abstractions.

[ . . . ]

Very God of very God, a real incarnation, genuine, full, and free forgiveness, life, salvation and communion with the Holy Trinity, imparted in the divinely powerful gospel and sacraments – including the evangelic doctrine as revealed, heavenly truth, not academic guesswork, and the true body and blood of Christ in the Sacrament of the Altar – all these mysteries to be cherished and handled for the common good by responsible householders in the God-given office, rightly dividing law and gospel (sola fide!): do not these constitute the “structure of Lutheranism”?

[ . . . ]

Luther insists just as rigidly, as does the Formula, on a radical differentiation between imputed and inchoate righteousness, only his terms for this are “passive” and “active” righteousness. Luther devotes a whole introductory section to this topic, under the title, “The Argument of St. Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians.” The distinctively “Christian righteousness,” by which alone we are justified and saved, “is heavenly and passive,” that is, Christ’s. All the various forms of earthly, active righteousness are excluded from this.

[ . . . ]

Luther’s sublime comment on Psalm 5:2-3 provides a suitable conclusion:

By the reign of His humanity or (as the Apostle says) His flesh, which takes place in faith, He conforms us to Himself and crucibles us, making genuine men, that is wretches and sinners, out of unhappy and haughty gods. For because we rose in Adam towards the likeness of God, He came down into our likeness, in order to lead us back to a knowledge of ourselves. And this takes place in the mystery [sacramentum] of the Incarnation. This is the reign of faith, in which the Cross of Christ holds sway, throwing down a divinity perversely sought and calling back a humanity [with its] despised weakness of the flesh, which had been perversely abandoned. But by the reign of [His] divinity and glory He will conform [configurabit] us to the body of His glory, that we might be like Him, now neither sinners nor weak, neither led nor ruled, but ourselves kings and sons of God like the angels. Then will be said in fact “my God,” which is now said in hope. For it is not unfitting that he says first “my King” and then “my God,” just as Thomas the Apostle, in the last chapter of Saint John, says, “My Lord and my God.” For Christ must be grasped first as Man and then as God, and the Cross of His humanity must be sought before the glory of His divinity. Once we have got Christ the Man, He will bring along Christ the God of His Own accord.

[0perationes in Psalmos (1519-1521), WA 5128-129. I am indebted for this reference to Walter Mostert, “Martin Luther- Wirkung und Deutung,” in Luther im Widerstreit der Geschichte, Veroffentlichungen der Luther-Akademie Ratzeburg, Band 20 (Erlangen: Martin-Luther Verlag, 1993), 78.]

***