– – – A Classic Case Study of Inadvertent Approximation of the Very Catholic Teaching He Ostensibly Opposes – – –

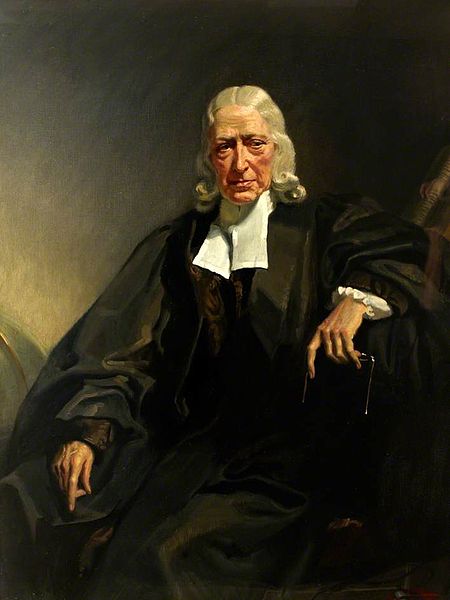

Portrait of Wesley by Frank O. Salisbury, c. 1932 [public domain / Wikimedia Commons]

I have noted on many occasions in the course of my research and apologetics dialogues, how Protestants (even major Protestant figures) will not infrequently hold an opinion highly similar to some particular Catholic belief, while at the same time railing against said Catholic belief, seemingly blissfully unaware of how close their own position is to the Catholic one. In most such cases, I think it is a matter of the Protestant being inadequately informed as to the precise nature of the Catholic belief. He or she fights a straw man; wars against a mere caricature of the actual Catholic teaching. If the belief were accurately understood in the first place, in these instances, it would actually be a welcome opportunity to find some common ground.

I believe this to be the case with regard to John Wesley and purgatory. He condemns the “Romish doctrine” — yet I contend that once his own views are closely scrutinized, they turn out to be scarcely different from what Catholics believe with regard to purgatory. I noted this again and again in the course of my compiling his statements for my book, The Quotable Wesley (completed on 2 May 2012). I’d like to now use this interesting example as very illustrative of a general polemical tendency among Protestants.

Another similar dynamic I noticed in Wesley during my recent research was his denunciation of merit per se, yet simultaneous definition of “reward” in a way that it is virtually identical with what Catholics truly believe with regard to merit (“God crowning his own gifts”: as St. Augustine put it: a line that is cited in the Catholic Catechism). Thus Wesley ends up condemning the notion of merit by that term, while practically asserting the same idea under another word. He even (almost sheepishly) notes in one place that he rejects merit, strictly speaking, but that “in a loose sense, meritorious means no more than rewardable” (Letter to his brother, Charles Wesley ; 3 August 1771). Elsewhere Wesley dances on the head of a pin again, with this issue:

Not by the merit of works, but by works as a condition. What have we then been disputing about for these thirty years? I am afraid, about words. As to merit itself, of which we have been so dreadfully afraid: we are rewarded ‘according to our works,’ yea, because of our works. How does this differ from ‘for the sake of our works’? And how differs this from ‘secundum merita operum’?— As our works deserve? Can you split this hair? I doubt, I cannot.” (Large Minutes; 1770)

What Wesley teaches about works as the condition of salvation is not a whit different from what Catholics teach about merit. It’s understood in both cases that the works and the merit as a result are entirely products of God’s grace. Wesley knows that full well (as to his own traditional Anglican position), but he appears to not know that it is Catholic teaching as well. And so, because of that misunderstanding or ignorance, he splits hairs over the word “merit.” He does seem to realize what is going on, though, in the probing analysis of the sentiment above.

With regard to purgatory, it’s a very analogous process: he winds up teaching the notions that are the major marks of purgatory and its purpose, while denouncing it by name. He also seems reluctant at a gut level — for some reason — to believe in continuing purging processes that he acknowledges in this life, as present also in the next life, while at the same holding that there are intermediate states, and that it is our duty to pray for those who are there. I will argue that this is internally inconsistent: that by his own interior logic and the biblical data, he should have come close to purgatory per se (just as, e.g., C. S. Lewis did: actual belief in purgatory as an Anglican).

I suppose, however, that in his circumstances: being accused as a “Jesuit” or a “papist” by hostile Anglicans, and of being a Pelagian (advocate of works-salvation) by Calvinists, Wesley was not exactly in a very good position to assert a “distinctively Catholic” position, even if he did become convinced of it. The order of the day in good olde merrie England was anti-Catholicism. Judged in the light of that 18th-century context, Wesley (highly influenced early on by Thomas a Kempis) shows himself extraordinarily ecumenical in other statements regarding Catholicism, and is not properly categorized as “anti-Catholic” (one who denies that Catholicism as a system is Christian). But that is another topic beyond our present purview.

Wesley clearly disavowed what he understood to be purgatory, as defined by Catholics:

. . . that those who die in a state of grace go into a place of torment, in order to be purged in the other world, is utterly contrary to Scripture. (Popery Calmly Considered; 1779)

He nevertheless accepted the premise that underlies our belief in the necessity of purgatory (in most cases):

. . . far other qualifications are required, in order to our standing before God in glory, than were required in order to his giving us faith and pardon. In order to this, nothing is indispensably required, but repentance, or conviction of sin. But in order to the other it is indispensably required, that we be fully cleansed from all sin: that the very God of peace sanctify us wholly, even . . . our entire body, soul, and spirit. . . . it is necessary in the highest degree, that we should thus wait upon him after justification. Otherwise, how shall we be ‘meet to be partakers of the inheritance of the saints in light?’ (Answer to the Rev. Mr. Church’s “Remarks on the Rev. Mr. Wesley’s Last Journal”; 2 February 1745)

Q. 2. What will become of a Heathen, a Papist, a Church of England man, if he dies without being thus sanctified? A. He cannot see the Lord. (Minutes of the Methodist Conference at Bristol; 2 August 1745)

. . . all writers whom I have ever seen till now (the Romish themselves not excepted) agree, that we must be fully cleansed from all sin, before we can enter into glory. (The Principles of a Methodist Farther Explained; 17 June 1746)

“Without holiness no man shall see the Lord,” shall see the face of God in glory. Nothing under heaven can be more sure than this: . . . (A Blow at the Root; 1762)

All holiness must precede our entering into glory. (A Letter to the Rev. Dr. Horne; 5 March 1762)

None go to heaven without holiness of heart and life: . . . (Letter to Samuel Sparrow, Esq.; 28 Dec. 1773)

Thus far is agreement, and (as I have argued many times) the only difference lies in the time and duration involved, and whether this “cleansing” or “purging” can occur after death. Wesley acknowledges this in his words just prior to the 1746 quote above:

Indeed men do not agree in the time. Some believe it is attained before death: some, in the article of death: some, in an after-state; in the mystic, or the popish purgatory.

Wesley famously held the doctrine of perfection, or entire sanctification. Here he defines that vastly misunderstood doctrine for us:

I want you to be all love. This is the perfection I believe and teach. . . . to set perfection too high, (so high as no man that we ever heard or read of attained,) is the most effectual (because unsuspected) way of driving it out of the world. (Letter to Miss Furly; 15 Sep. 1762)

Absolute or infallible perfection, I never contended for. Sinless perfection, I do not contend for, seeing it is not scriptural: . . . I acknowledge no such perfection; I do now, and always did protest against it. (Letter to Mrs. Maitland; 12 May 1763)

The perfection I hold is so far from being contrary to the doctrine of our Church, that it is exactly the same which every Clergyman prays for every Sunday: “Cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of thy Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love thee, and worthily magnify thy holy name.” I mean neither more nor less than this. In doctrine, therefore, I do not dissent from the Church of England. (An Answer to Mr. Rowland Hill’s Tract, Entitled, “Imposture Detected”; 28 June 1777)

. . . I advise you, frequently to read and meditate upon the thirteenth chapter of the First Epistle to the Corinthians. There is the true picture of Christian perfection! Let us copy after it with all our might. (Letter to Miss Ann Loxdale; 12 April 1782)

Briefly explained, he did not believe that every Christian received a “second blessing”: at which time he or she became a perfect saint or angel. This was the caricature of his teachings that his opponents pushed (and still do, to this day). In fact, Wesley believed that he himself had not attained this entire perfection:

I never told you so, nor any one else. I no more imagine that I have already attained, that I already love God with all my heart, soul, and strength, than that I am in the third heavens. (Letter to “John Smith” [probably one of the Archbishops of Canterbury, Thomas Herring or Thomas Secker]; 22 March 1748)

I have told all the world I am not perfect; and yet you allow me to be a Methodist. I tell you flat, I have not attained the character I draw. (Letter to the editor of Lloyd’s Evening Post; 5 March 1767)

He refers to the relative rarity of such a momentous work of grace:

. . . few of those to whom St. Paul wrote his Epistles were so [sanctified] at the time he wrote: . . . Nor he himself at the time of writing his former Epistles: . . . (Minutes of the Methodist Conference at Bristol; 2 August 1745)

This being the case, it’s fascinating that Wesley feels led to conclude (in order to be consistent with the parameters he sets for himself in his own reasoning) that the entire sanctification occurs shortly before death, in order to make a man fit for heaven:

But none who seeks it sincerely shall or can die without it; though possibly he may not attain it, till the very article of death. . . . we grant, . . . That the generality of believers whom we have hitherto known were not so sanctified till near death: . . . (Minutes of the Methodist Conference at Bristol; 2 August 1745)

We grant that many of those who have died in the faith, yea, the greater part of them we have known, were not sanctified throughout – not made perfect in love – till a little before death. (Minutes of the Methodist Conference of 17 June 1747)

I believe this perfection is always wrought in the soul by a simple act of faith; consequently, in an instant. . . . As to the time. I believe this instant generally is the instant of death, the moment before the soul leaves the body. (A Plain Account of Christian Perfection; 27 Jan. 1767)

My question for Wesley, and (since he is no longer with us: at least on earth) those who think as he does is, however: why the felt necessity or urge to make all this happen before death? Nothing in Scripture that I recall confines such purging to this life. Is it not a further act of God’s mercy to accept those not fully cleansed of sin into the fold of the saved elect, by means of purgatorial cleansing, making them appropriately cleansed in order to enter into His presence? The Bible no more indicates that such a cleansing will occur right before death, than it refers (very often) to purging after death.

But I dare say there is more data about it occurring after death than right before. The judgment seat of Christ, e.g. (2 Cor 5:10) is after death, and it arguably involves some sort of purging, insofar as it is able to be distinguished at all from the Last Judgment. Whatever is going on in 1 Corinthians 3 (sure seems amazingly like purgatory: even mentioning “fire” in some sense) is after death, in the next life. Why, then, does Wesley assert purging prior to death while vehemently denying the same thing after death? It seems wholly arbitrary and based on nothing logically or biblically substantial. What we are informed of repeatedly in the Bible is the divinely ordained process of cleansing and its purpose: not so much how long it takes or when it happens.

In any event, Wesley acknowledges — many times — that processes of purging occur in this life. What he describes is (for my money) scarcely distinguishable from what a Catholic understands concerning purgatory: its purpose and goals both:

So the Lord has chastened and corrected you; but he hath not given you over unto death. It is your part to stand ready continually for whatever he shall call you to. Every thing is a blessing a means of holiness, as long as you can clearly say, “Lord, do with me and mine what thou wilt, and when thou wilt, and how thou wilt.” (Letter to Miss Bosanquet; 16 Aug. 1767)

The refiner’s fire purges out all that is contrary to love, and that many times by a pleasing smart. Leave all this to Him that does all things well, and that loves you better than you do yourself. (Letter to Walter Churchey; 21 Feb. 1771)

Conflicts and various exercises of soul are permitted; these also are for good. If Satan has desired to have you to sift you as wheat, this likewise is for your profit: You will be purified in the fire, not consumed, and strengthened unto all longsuffering with joyfulness. (Letter to Mrs. Mary Savage; 6 May 1771)

. . . it is good for you that every grain of your faith should be tried; afterwards you shall come forth as gold. See that you never be weary or faint in your mind; account all these things for your profit, that you may be a full partaker of His holiness, . . . (Letter to Miss Pywell; 29 Dec. 1774)

Gold is tried in the fire, and acceptable men in the furnace of adversity. . . . You are suffering the will of God, and glorifying him in the fire. “But I am not increasing in the divine life.” That is your mistake. Perhaps you are now increasing therein faster than ever you did since you were justified. (Letter to Miss Loxdale; 9 March 1782)It has pleased God, for many years, to lead you in a rough and thorny way. But he knoweth the way wherein you go; and ‘when you have been tried, you shall come forth as gold.’ (Letter to Mrs. Jane Barton; 23 April 1783)

For it is not an easy thing always to remember, (then especially when we have most need of it,) that “the Lord loveth whom he chasteneth, and scourgeth every son whom he receiveth.” Who could believe it, if he had not told us so himself? (Letter to Mrs. Jane Barton; 11 June 1788)

A second way to critique Wesley’s views from a Catholic perspective is to inquire as to the purpose of praying for the dead in the intermediate state. He accepts both things. First, here is what he writes about the intermediate state, or what he usually terms Paradise; alternately known as Sheol or Hades, or, sometimes, the limbo of the fathers:

Even in paradise, in the intermediate state between death and the resurrection, we shall learn more concerning these in an hour than we could in an age during our stay in the body. (Letter to Miss B; 17 April 1776)

In paradise the souls of good men rest from their labours, and are with Christ from death to the resurrection. This bears no resemblance at all to the Popish purgatory, wherein wicked men are supposed to be tormented in purging fire, till they are sufficiently purified to have a place in heaven. But we believe, (as did the ancient church,) that none suffer after death, but those who suffer eternally. We believe that we are to be here saved from sin, and enabled to love God with all our heart. (Letter to George Blackall; 25 Feb. 1783)

. . . Paradise: the place “where the wicked cease from troubling, and where the weary are at rest:” the receptacle of holy souls, from death to the resurrection. . . . paradise is not heaven. It is, indeed, (if we may be allowed the expression,) the anti-chamber of heaven, where the souls of the righteous remain, till, after the general Judgment, they are received into glory. (Sermon 112: The Rich Man and Lazarus; 25 March 1788)

. . . Hades, namely, the invisible world. . . . (which is the receptacle of separate spirits,) from death to the resurrection. Here we cannot doubt but the spirits of the righteous are inexpressibly happy. (Sermon 122: On Faith; 17 Jan. 1791)

Wesley firmly believes in praying for these souls:

It is certain “praying for the dead was common in the second century,” . . . you might have said, and in the first also; seeing that petition, Thy kingdom come, manifestly concerns the saints in Paradise, as well as those on earth. . . . Praying thus far for the dead, ‘That God would shortly accomplish the number of His elect, and hasten His Kingdom,’ you will not easily prove to be any corruption at all. (A Letter to the Rev. Dr. Conyers Middleton Occasioned by His Late Free Inquiry; 4 Jan. 1749)

Your fourth argument is, That in a collection of Prayers, I cite the words of an ancient Liturgy—’for the Faithful Departed.’ Sir, whenever I use those words in the Burial Service, I pray to the same effect: ‘That we, with all those who are departed in Thy faith and fear, may have our perfect consummation of bliss, both in body and soul.’ Yea, and whenever I say, ‘Thy Kingdom come;’ for I mean both the kingdom of grace and glory. In this kind of general prayer, therefore, for the Faithful Departed, I conceive myself to be clearly justified, both by the earliest Antiquity, by the Church of England, and by the Lord’s Prayer. (Second Letter to Bishop George Lavington; 27 Nov. 1750)

But what is the purpose of such prayers? Catholics point out that those perfected in heaven are in need of neither help, nor prayer. Those in hell are beyond all redemption and help. All parties agree that judgment as to one’s eternal destiny occurs at death Hence, it is meaningless to pray for either of those parties. It does make sense, though, to pray for those in transition from this world, to heaven. But what for? Well, we Catholics say it is an act of grace to lessen their time or amount of expiatory suffering in purgatory: God applying the grace-filled effects of prayer to the recipient (just as in all intercessory prayer). Otherwise, what is it for? Wesley expressly denies the Catholic sense of the prayer, but offers us no cogent alternative:

But it is far from certain, that “the purpose of this was, to procure relief and refreshment to the departed souls in some intermediate state of expiatory pains;” or, that this was the general “opinion of those times.” (A Letter to the Rev. Dr. Conyers Middleton Occasioned by His Late Free Inquiry; 4 Jan. 1749)

Catholics submit, again, that the existence and process of purgatory after death is the most plausible background explanation of such prayers. Wesley does indeed at times admit some sort of process of continuing perfection after death (though not clearly defined):

But as happy as the souls in Paradise are, they are preparing for far greater happiness. For Paradise is only the porch of heaven; and it is there the spirits of just men are made perfect. (Sermon 73: Of Hell; 10 Oct. 1782; my italics)

. . . on the other hand, can we reasonably doubt, but that those who are now in Paradise, in Abraham’s bosom, all those holy souls, who have been discharged from the body, from the beginning of the world unto this day, will be continually ripening for heaven; will be perpetually holier and happier, till they are received into the “kingdom prepared for them from the foundation’ of the world?” (Sermon 122: On Faith; 17 Jan. 1791; my italics)

Exactly. Purgatory is the place / condition whereby (to use Wesley’s own words) “the spirits of just men are made perfect” and where they are “continually ripening for heaven” and “perpetually holier and happier” until, once and for all, they are fit to enter heaven and to see God face-to-face. If this occurs by “fire” (whether real or metaphorical), then Catholics argue, by analogy (like Wesley) from many instances of Scripture, that such refining and purification is precisely what helps to make us holy (metaphorically, “gold” or “pure”) and thus able to be in God’s presence forevermore. It all flows from God’s great mercy. He would rather refine us after death than send us to hell because we refused to allow Him to do His work of grace and purification and sanctification (indeed, perfection) in us before death.

Wesley says God zaps us in an instant right before death. We say it takes a little longer after death. No essential difference; no biggie. It’s the same result by different methods. Be that as it may, I maintain that purgatory is far more indicated in Holy Scripture than a “zap” right before death. See, e.g., 25 scriptural arguments, backed up by massive attestation from the Church fathers.

Wesley loved a good debate, was unfailingly amiable and quite skilled in that art, and (I think) uniformly bested his opponents. How I wish he were here to reply to this two-pronged argument! I think we would both enjoy the mutual challenges very much.