(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

I’m eleven hours off of my normal time zone and have been almost completely without internet access for the past couple of days or so. I apologize for being late in calling these new items from the Interpreter Foundation to your notice, but I had little alternative. They went up on Thursday and Friday:

“Jeremiah “the Prophet,”” written by Loren Blake Spendlove

Abstract: This article, which focuses on the role of Jeremiah as a prophet, is based on a study of the Hebrew Bible and the Greek Septuagint. It also analyzes references to Jeremiah in the Book of Mormon and connects those references to current scholarly research on the book of Jeremiah. Consistent with the general consensus among biblical scholars today, as well as Nephi1’s own references to Jeremiah in the Book of Mormon, the author proposes that even though Jeremiah embodied the office of a prophet, he was not recognized as being “among the prophets” during his lifetime. This is a subtle yet significant difference. If this view is correct, it would further substantiate the alignment between the Book of Mormon and contemporary scholarly perspectives on the historical reception of Jeremiah’s identity as a prophet in antiquity.

“Interpreting Interpreter: Jeremiah’s Prophetic Title,” written by Kyler Rasmussen

This post is a summary of the article “Jeremiah ‘the Prophet’” by Loren Spendlove in Volume 64 of Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship. All of the Interpreting Interpreterarticles may be seen at https://interpreterfoundation.org/category/summaries/. An introduction to the Interpreting Interpreter series is available at https://interpreterfoundation.org/interpreting-interpreter-on-abstracting-thought/.

A video introduction to this Interpreter article is now available on all of our social media channels, including on YouTube at https://youtube.com/shorts/El4SP5Ndlic.

The Takeaway: Spendlove argues, based on evidence from the Septuagint and the Dead Sea Scrolls, that Jeremiah was not initially listed as “among the prophets” by his contemporaries, a fact that’s reflected in how he’s referred to by Nephi in the Book of Mormon.

The Temple: Plates, Patterns, & Patriarchs: “The Cosmic Temple of Divine Names: Sapiential, Nomistic, and Numerical Properties,” written by Samuel Zinner:

Part of our book chapter reprint series, this article originally appeared in The Temple: Plates, Patterns, & Patriarchs, edited by Stephen D. Ricks and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw. For more information, go to https://interpreterfoundation.org/books/the-temple-plates-patterns-patriarchs/. For video and audio recording of this conference talk, go to https://interpreterfoundation.org/conferences/2022-temple-on-mount-zion-conference/videos/zinner/.

“As Alexandra Grund documents, the typical ancient Near Eastern creation story tends to end with the establishment of a divine temple, in which the king is crowned as a symbol of bringing cosmic order out of chaos.1 By contrast, Genesis’s first creation story reaches its apex with the establishment of the divine Sabbath.”

We flew roughly north northeast last night, mostly across Iran, over Bandar Abbas, Kerman, Rafsanjan, and Mashhad. I’m not sure, but we may also have passed over the northwestern corner of Afghanistan. (If so, that would surprise me just a tiny bit.) Then we passed over Bukhara and on to Samarkand, traveling by air a small part of the ancient Silk Road. Unfortunately, all was dark (except, of course, for the occasional lights of urban sprawl).

My first impression of Samarkand — at 4 AM, still pitch black — was of a surprisingly clean and orderly city with well-kept streets and, at frequent intervals, beautiful decorative arrangements of lights along the major boulevard that we mostly followed. Those arrangements were in patterns that were familiar to me from what I know of the regional Islamicate artistic and architectural tradition — which, of course, echoes in multiple elegant but refracted ways the broader design elements of Islamicate art from India to Spain. Literally so: The repeated geometric design on the marble floor of our hotel’s large atrium is a very familiar one that I’ve often pointed out to students as appearing in both the Alhambra in Andalusia and on the grounds of India’s Taj Mahal. It was already fun for me, also, to see elements of Islamicate civilization reflected in the street signs and markers on the way in to the hotel — familiar and yet somewhat unfamiliar. There was, for instance, a sign indicating the direction of the Markaz — an Arabic term for the “(presumably city) center,” but adopted here into Roman letters and Uzbek. And sometimes the Arabic loanwords were rendered in Cyrillic. (Russian is still widely spoken here, after years of Soviet occupation.) There was also a pointer toward Hadarat Kidr, meaning something like “His Excellency the Green [One]” or “His Presence the Green [One],” which is almost certainly a reference, in turn, to something that must be connected with common Islamic legends about the Prophet Elijah. (I need to find out what the specific reference here in Samarkand might be.)

The conference for which I’ve come actually begins tomorrow — some of our people are still on their way here — so we did an afternoon tour of some of the principal sights of Samarkand. I’ve read and even sometimes taught about them for many years, so it was gratifying finally to actually see them.

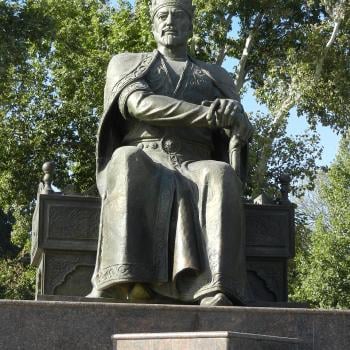

First, we spent a fair amount of time at the Gūr-i Amīr, the mausoleum of the Turkic conqueror Timur (who is often known the West as Tamerlane). I’ve noticed that Timur, who founded the large but relatively short-lived Timurid Empire, is treated as a hero here. (There is, for example, a larger than life-sized statue of an enthrone Timur located in a park within easy walking distance of our hotel.) In my opinion, though, Timur is another of those who are called “x the Great” who don’t really deserve that title. A few weeks ago, I was roundly attacked as a racist and a white supremacist over on the Peterson Obsession Board for having expressed reservations here about applying the title the Great to the Hawaiian king, unifier, and conqueror Kamehameha I, who killed many hundreds pr thousands of people in order make himself ruler over all of the islands. While we were under the dome of the Gūr-i Amīr, listening to our guide praise Timur, one of the Iranian scholars with whom we’re meeting leaned over to me and whispered “He was a horrible person, you know.” I couldn’t agree more. He was a brilliant conqueror, but he was brutal and cruel even by the standards of highly successful ancient and medieval warlords. Pathologically so, in my judgment.

Babur, who founded the Mughal dynasty in India, was a descendent of Timur. Unsurprisingly, in that light, the design of Gūr-i Amīr has plain echoes in the architecture of later Mughal tombs (e.g., the Gardens of Babur, the Tomb of Humayun, and, most famously, Shah Jahan’s incomparable Taj Mahal.

We also went to the Registan, which was the public square for the Timurid capital city. But I may report on that tomorrow. And don’t let me forget to tell you about “the curse of Timur.” Jet lag is affecting me powerfully right now. I can scarcely keep my eyes open. I’ve just returned from having dinner with my friend Randy Paul and some of the Iranian participants in our conference. Good people..

Posted from Samarkand, Uzbekistan