A couple of weeks ago, I read Cassidy Nichole Pyper, ““Not Only Men but Women Also”: An Argument for Alma’s Intentional Inclusion of Women,” BYU Studies 64/1 (2025): 21-44. I have to admit that, when I began the article, I wasn’t really expecting much. Sister Pyper contends, for example, that, when the Book of Mormon refers to, or addresses, “brethren,” that term can and should generally be taken to include women, sisters, as well. But I’ve assumed that more inclusive sense for as long as I can remember, and, just as many General Authorities of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have often done when citing such passages in a lesson or a talk, I’ve commonly inserted a bracketed reference to “sisters” into the actual language of the Book of Mormon.

But Sister Pyper’s argument is somewhat weightier than that, and more seriously argued. So, if this is a topic that interests you or that concerns you, or that interests or concerns somebody you know, I commend “An Argument for Alma’s Intentional Inclusion of Women” to your attention.

And I note one particular passage very near the end of the article:

While the general lack of female representation in the text remains a question for readers and scholars to wrestle with, careful analysis suggests that a slow and deliberate reading of the Book of Mormon may reveal a much less androcentric text than many readers have perceived it to be. That itself is good news for those who embrace the book as scripture in the twenty-first century. Joseph Spencer agrees that “the Book of Mormon, despite initial appearances, has much of interest and relevance to say about gender.” (43-44)

In support of such an expectation, I call attention to a pair of articles that I myself published quite a few years ago:

Daniel C. Peterson, “Nephi and His Asherah,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: 9/2 (2000): 16-25

Abstract: Asherah was the chief goddess of the Canaanites. She was El’s wife and the mother and wet nurse of the other gods. At least some Israelites worshipped her over a period from the conquest of Canaan in the second millennium before Christ to the fall of Jerusalem in 586 BC (the time of Lehi’s departure with his family). Asherah was associated with trees—sacred trees. The rabbinic authors of the Jewish Mishna (second–third century ad) explain the asherah as a tree that was worshipped. In 1 Nephi 11, Nephi considers the meaning of the tree of life as he sees it in vision. In answer, he receives a vision of “a virgin, . . . the mother of the Son of God, after the manner of the flesh.” The answer to his question about the meaning of the tree lies in the virgin mother with her child. The virgin is the tree in some sense and Nephi accepted this as an answer to his question. As an Israelite living at the end of the seventh century and during the early sixth century before Christ, he recognized an answer to his question about a marvelous tree in the otherwise unexplained image of a virginal mother and her divine child—not that what he saw and how he interpreted those things were perfectly obvious. What he “read” from the symbolic vision was culturally colored. Nephi’s vision reflects a meaning of the “sacred tree” that is unique to the ancient Near East. Asherah is also associated with biblical wisdom literature. Wisdom, a female, appears as the wife of God and represents life.

However, I personally prefer the much longer book chapter from which the article above was condensed and derived: Daniel C. Peterson, “Nephi and His Asherah: A Note on 1 Nephi 11:8–23,” in Mormons, Scripture, and the Ancient World: Studies in Honor of John L. Sorenson (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1998), 191–243.

And these might also be helpful:

- Daniel C. Peterson, “A Divine Mother in the Book of Mormon?” in Mormonism and the Temple: Examining an Ancient Religious Tradition, ed. Gary N. Anderson (Logan, Utah: Academy for Temple Studies/USU Religious Studies, 2013), 109–124;

- John S. Thompson, “The Lady at the Horizon: Egyptian Tree Goddess Iconography and Sacred Trees in Israelite Scripture and Temple Theology,” in Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 38 (2020): 153-178.

As well as these, from scholars outside of the Latter-day Saint tradition:

- Margaret Barker, “Joseph Smith and Preexilic Israelite Religion,” in The Worlds of Joseph Smith, ed. John W. Welch (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2005), 69–82.

- Margaret Barker, “The Fragrant Tree,” in The Tree of Life: From Eden to Eternity, ed. John W. Welch and Donald W. Parry (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book and Neal A. Maxwell Institute, 2011), 55–79. [Unfortunately, I don’t have an online link for this one.]

- Samuel Zinner, “‘Zion’ and ‘Jerusalem’ as Lady Wisdom in Moses 7 and Nephi’s Tree of Life Vision,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 12 (2014): 281–323.

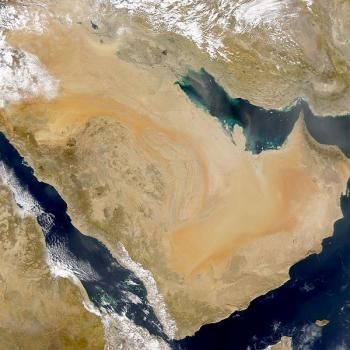

Nothing comes from nothing. Nothing ever could. So, somewhere in my youth or childhood, I must have done something good. Because not only was our flight from Houston to Dubai on Emirates, which fully deserves its reputation as one of the world’s best airlines — the aircraft was beautifully appointed, very clean and new, the food was excellent even in economy class, and the cabin crew (between them) spoke seventeen languages –but I had a window seat and an entire row to myself! I actually got in about three hours of sleep during the nearly fifteen-hour flight. That is about as well as I’ve ever done, even with the use of chemicals. I also read a short book about the British Museum, began a mystery novel by Dorothy Sayers, watched Conclave (which seemed somehow appropriate), the biopic A Complete Unknown (about Bob Dylan) — I’ve long been a big fan of Pete Seeger, Dylan, and Joan Baez — and a Second World War movie called Wolves of War.

We flew over Iraq just now, slightly to the east of Mosul and Baghdad. Alas, though, it was becoming dark and nothing was really visible. I think that I’ve only been in the airport here in Dubai once before. It’s enormous. Ou

Posted from Dubai, United Arab Emirates