On Saturday, 5 April, my friend Don Bradley lost his son Donnie suddenly, in an unspeakably tragic and horrible incident. (I don’t feel that, on my own initiative, I can go further into the details of what happened.) I’ve spoken with Don within the past few hours. As you can easily imagine, he is absolutely grief-stricken. He has now set up a gofundme account in honor of his boy:

Help Extend Donnie’s Legacy of Love through UNICEF

FOR DONNIE’S BIRTHDAY, AND IN CELEBRATION OF HIS LIFE THAT PASSED TOO SOON, PLEASE HELP HIM FULFILL HIS DREAM OF CONTRIBUTING TO THE LIVES OF CHILDREN AROUND THE WORLD.When Donnie Bradley was a little boy he wanted to make other children happy like he was. When he was just 3, he dictated to his dad a letter to President Clinton about how to make the lives of children in poor nations better. All through his childhood on Halloween he would not only collect candy for himself but also donations to help other children around the world through a program called “Trick or Treat for UNICEF.” UNICEF helps nourish, protect, and educate children in over 190 nations and give them good lives.Before Donnie died this month he told us, his family, over and over how what he wanted most was to contribute to the lives of others. By donating to save the lives of children through UNICEF, as Donnie himself worked to do when he was just a child himself, you can help Donnie fulfill his dreams.

I doubt that William Shakespeare’s King Lear had modern air travel in mind when he said that

“Men must endure/Their going hence, even as their coming hither: Ripeness is all.” (King Lear V.ii)

Maybe I’m being too hasty, though. After all, there were, for many years, such things as Lear jets. In any case, I begin this morning in dread of the next many hours of sardine-class international flying. With something like the same degree of enthusiasm, I suppose, with which a condemned man contemplates the gallows on his last morning. This trip seemed like a good idea when I accepted the invitation several months ago . . .

On the website of the completely static and moribund Interpreter Foundation, Brant A. Gardner continues with his important new blog series, which was first launched last week: “The Heartland Versus Mesoamerica Part 2: The Heartland “Pins” in the Map”

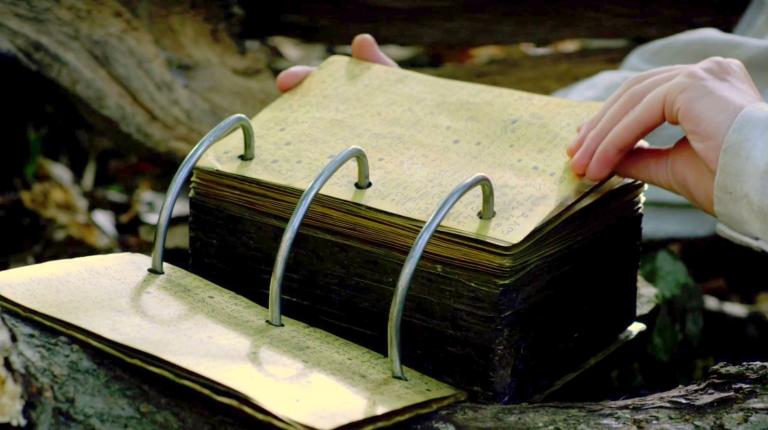

A few weeks back, I read. Richard Lyman Bushman, “What Are We to Make of the Gold Plates?” BYU Studies 64:1 (2025): 97-113. Here are a pair of passages from his very interesting article:

If you want to believe in the gold plates, as I do, a case can be made. Accepting their reality does not require a complete abandonment of rationality. Foremost among the evidences are the eleven men besides Joseph Smith who say they saw the plates. Their statements, printed in the Book of Mormon, were never repudiated. I am impressed that Oliver Cowdery wrote a friend about the experience in October 1829 soon after the vision of the plates was alleged to have occurred.6 The witnesses saw something.

Beyond the witnesses are all the people who touched or lifted the plates while they were in Smith’s possession. The evidence for Smith having something like the plates was strong enough to persuade Dan Vogel, a skeptical historian, that Smith possessed some object with their shape, size, and weight, perhaps a set of tin plates he fabricated.7 I don’t subscribe to Vogel’s tin-plate hypothesis, but I do think the plates were a tactile reality to the people around Smith.

Then there was a personal experience with the Egyptologist Richard Parker. While I was at Brown University on a fellowship in 1965, I asked Parker, a member of the faculty, about an article by Ariel Crowley on the Anthon Transcript. Crowley examined the characters copied from the plates for Martin Harris to show to the Columbia linguist Charles Anthon. Crowley compared each character on the transcript to characters from Egyptian lexicons. Every one of over two hundred characters had an Egyptian equivalent.8 When I called on Parker to ask about the validity of Crowley’s argument, I was surprised to learn that Parker himself had helped Crowley locate the characters. Were they really Egyptian? I asked. Not really, he said. They were more like Meroitic, an upper Nile language that was written in Egyptian characters but was an independent tongue. That seemed to me to fit the idea of Hebrew being written in Egyptian as the Book of Mormon describes its own text. The experience left me with a conviction that Joseph had access to Egyptian from somewhere, and perhaps it was from the plates. All of this—the witnesses, the many touches and lifts, and the Anthon characters—makes an argument for the plates that I can buy.

In addition, the plates are embedded in a story that concludes with a published text, the Book of Mormon, which is itself a marvel. I cannot conceive of Joseph Smith writing that book on his own. It is too complex, too weird, too compelling to be a product of his twenty-four-year-old mind. For me, the book’s text disrupts any simple explanation of its origins. Adding gold plates and an inspired translation to the mix seems to me in keeping with the extraordinary nature of the book.

I have lived with the gold plates long enough—all my life—not to be offended by their existence. They seem beautiful and strange in a wonderful way. They don’t strike me as an excrescence or offense. A gold book telling the story of two fallen civilizations written in a mysterious hybrid of Egyptian and Hebrew is astounding. It is a fitting introduction to the unusual qualities of Mormon theology. I am happy to live in a world I share with the gold plates. (107-108)

Continuing a few pages later, he writes that,

As John Peters said, they stand apart from other forms of witness in their billiard-ball tactility. They were a thing, a heavy stack of metal sheets Joseph had to lug home from the hill. They were hidden under the floorboards and covered with a cloth. They were held and balanced on a knee.

Moreover, witnesses saw and felt the plates. “The translator of this work, has shown unto us the plates of which hath been spoken, which have the appearance of gold; and as many of the leaves as the said Smith has translated we did handle with our hands; and we also saw the engravings thereon.”12 We may not review the witnesses’ statements very often or teach them in our classes, but they remain there in the front of every copy of the Book of Mormon as a tactile obstacle to disbelief. The gift of the witnesses and the publication of their statements in every Book of Mormon indicates to me that we are meant to remember the plates, to value them as evidence much as Christ’s wounds testify of the Resurrection.

For me, this is the meaning of the plates. They are the most durable, forceful support for the historical side of our religion. They tie us primarily to one figure—the angel Moroni. But in leaving space for him, they open a way for other heavenly visitors. The plates prop open the door to an ensemble of angelic beings entering ordinary life.

If we give up on the plates by letting them fall into disuse, never having them in mind, never discussing them, we lose the most tangible proof of divine persons entering history. We risk letting the historical side of our faith slip away. We may not dwell on the plates or always expound on them, but we certainly do not want to forget them. (112)