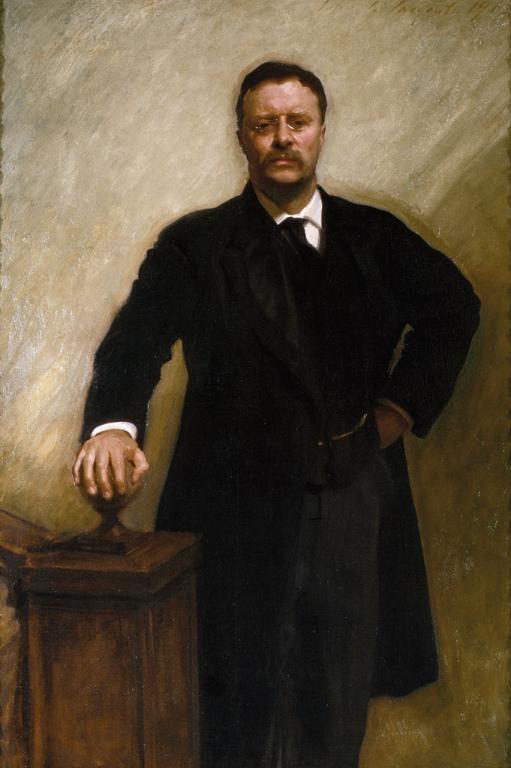

(John Singer Sargent, public domain)

The former president of the United States Theodore Roosevelt, slightly more than a year out of office, delivered perhaps his most famous speech at the Sorbonne in Paris on 23 April 1910. Although its formal title is “Citizenship in a Republic,” it is probably more widely known as “The Man in the Arena.” His statements at the Sorbonne were part of a larger European trip that also included visits to Vienna, Budapest, and Oslo, where on 5 May 1910, he delivered his acceptance speech for the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize, which he had won for his efforts in bringing an end to the Russo-Japanese War. I share here the most famous passage from “Citizenship in a Republic” — a personal favorite of mine, for whatever that’s worth — accompanied by the important paragraph that precedes it and some of the important lines that follow it:.

Let the man of learning, the man of lettered leisure, beware of that queer and cheap temptation to pose to himself and to others as a cynic, as the man who has outgrown emotions and beliefs, the man to whom good and evil are as one. The poorest way to face life is to face it with a sneer. There are many men who feel a kind of twisted pride in cynicism; there are many who confine themselves to criticism of the way others do what they themselves dare not even attempt. There is no more unhealthy being, no man less worthy of respect, than he who either really holds, or feigns to hold, an attitude of sneering disbelief toward all that is great and lofty, whether in achievement or in that noble effort which, even if it fails, comes second to achievement. A cynical habit of thought and speech, a readiness to criticize work which the critic himself never tries to perform, an intellectual aloofness which will not accept contact with life’s realities—all these are marks, not as the possessor would fain to think, of superiority, but of weakness. They mark the men unfit to bear their part painfully in the stern strife of living, who seek, in the affectation of contempt for the achievement of others, to hide from others and from themselves their own weakness. The role is easy; there is none easier, save only the role of the man who sneers alike at both criticism and performance.

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat. Shame on the man of cultivated taste who permits refinement to develop into fastidiousness that unfits him for doing the rough work of a workaday world. Among the free peoples who govern themselves there is but a small field of usefulness open for the men of cloistered life who shrink from contact with their fellows. Still less room is there for those who deride or slight what is done by those who actually bear the brunt of the day; nor yet for those others who always profess that they would like to take action, if only the conditions of life were not exactly what they actually are. The man who does nothing cuts the same sordid figure in the pages of history, whether he be cynic, or fop, or voluptuary. There is little use for the being whose tepid soul knows nothing of the great and generous emotion, of the high pride, the stern belief, the lofty enthusiasm, of the men who quell the storm and ride the thunder. Well for these men if they succeed; well also, though not so well, if they fail, given only that they have nobly ventured, and have put forth all their heart and strength. It is war-worn Hotspur, spent with hard fighting, he of the many errors and the valiant end, over whose memory we love to linger, not over the memory of the young lord who “but for the vile guns would have been a valiant soldier.”

Negative reviews of the forthcoming Six Days in August film have been arriving in spurts from the usual suspects for many months now. And, although I haven’t yet read it, I’m told that a quite hostile critique has gone up just today. This is really quite impressive since, apart from my wife and I and the three principal filmmakers and their wives, I could probably count the number of those who have seen the entire film (even in its current rough form) on the fingers of two hands. Maybe four, if I’m really generous — but there would likely be fingers left over.

I’m serenely confident that, whatever its actual merits or demerits may prove to be, Six Days in August will be voted down in every place that it can be voted down by anti-Mormon zealots who haven’t seen it. That goes with the territory. It’s exactly what happened with our earlier film, Witnesses. To which I will respond, simply, that Theodore Roosevelt was entirely right in this regard: “The poorest way to face life is to face it with a sneer.”

It’s a matter of priorities, I suppose: “Average Americans spend 63 times more time on television than personal religious practice: Americans spend on average 2.4 minutes a day on personal worship, which is also 4 times less than what they spend on pet care, 8 times less than exercise, 9 times less than gaming, 12 times less than socializing and 28 times less than eating.”

Memory is an odd thing. I had two nightmares last night, divided from each other by my having actually awakened and gotten up between them. I can’t remember the actual plot of either one of them now, although I seem to recall that each (especially the second) had a very complex plot. I distinctly remember that the second prominently featured a disaster involving a Russian submarine called the Kursk. As soon as I woke up, I reached for my cell phone and looked up the word Kursk. I thought that I actually did vaguely remember, in real life, something about a disaster involving a Russian submarine called the Kursk, and I wanted to confirm that it was real.

It was, in fact, real. (See the Wikipedia article “Kursk Submarine Disaster.”) But why on earth did I dream about it last night? The story — a very sad one, it scarcely needs saying — has never loomed particularly large in my mind. What suddenly dredged it up from somewhere deep in my memory? I wish I could remember the plot of the dream. Perhaps that would shed some light.

Posted from Newport Beach, California