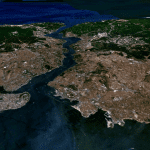

After breakfast, we visited the ancient Hippodrome, where chariot races were held in Byzantine days, and where the infamous massacre took place during the great Nika Riot of AD 532 (about which I hope to say more in a future entry).

Two monuments are (to me) particularly notable in the Hippodrome:

- The Serpent Column—Originally, this was the sacrificial Tripod of Plataea, which was created to celebrate the victory of the Greeks over the invading Persians during the Persian Wars of the fifth century BC. Emperor Constantine ordered the Tripod to be moved from the Temple of Apollo at Delphi and placed in middle of the Hippodrome. The top was once adorned with a golden bowl supported by three serpent heads, although it appears that this was never brought to Constantinople. The serpent heads and the top third of the column were destroyed in 1700, so that all that remains of the Delphi Tripod today is the base.

- In AD 390, the emperor Theodosius the Great brought a pink granite obelisk from the Temple of Karnak, in Luxor, Egypt, and placed it inside the racing track. The obelisk dates from around BC 1490, during the reign of Pharaoh Thutmose III. In order to move it to Constantinople, Theodosius had the obelisk cut into three pieces, of which this is the top section. It still stands today on the marble pedestal where Theodosius placed it.

The four gilded bronze horses on the facade of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice were stolen from Constantinople after the infamous Fourth Crusade of the early thirteenth century, which sacked the city and poisoned relations between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy for centuries. They were part of a quadriga, a brace of four chariot horses, that had adorned the Hippodrome until that time and that are the only equestrian team to have survived from classical Antiquity. Since 1974, happily, the four original horses have been preserved inside; the figures on the balcony over the central portal are copies.

The next stop was the Sultanahmet or Blue Mosque. Its nickname comes from the beautiful, blue ceramic tiles—Iznik tiles, bearing the name of the town famous for making them—that adorn the interior. (Iznik was formerly known as Nikaia or Nicaea, which was famous for making creeds. See? Historical progress does actually happen.)

We next visited a portion of the Topkapı Palace, one of the largest and oldest surviving palaces in the world. (Please notice the final i of Topkapı, which lacks a dot. That is deliberate, and specific to Turkish spelling. A dotless i is pronounced rather like a weak uh.) This was the seat of the Ottoman sultans until the erection of the more modern, European-style Dolmabahçe Palace over on the opposite or eastern shore of the Bosporus. In Turkish, that more modern palace is known as the Dolmabahçe Sarayı. Classical music lovers may recognize the Turkish word for “palace” in the title of Mozart’s 1782 opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail (English: The Abduction from the Seraglio, which has a Turkish setting).

Then, after lunch, we visited for a little while with Jeff Flake and his wife in the area between the Sultanahmet Mosque and the Hagia Sophia. He is the Latter-day Saint former senator from Arizona and the current ambassador of the United States to Türkiye. They offered some interesting observations on relations between Türkiye and America, as well as upon the state and progress of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints here.

We next walked over to (and through) the Basilica Cistern — there was great deal of walking today — which was built in AD 532, making it a contemporary of the Hagia Sophia. It was a part of the extraordinary water system of the Byzantine capital, which continues to be visible in some of the still-standing aqueducts that can be seen around the city. (We drove under an elegant and very large one this morning). You may have seen the Cistern in the 1963 James Bond film From Russia with Love, perhaps, or in the 2016 film version of Dan Brown’s Inferno.

Thereafter, we walked to the Grand Bazaar , which is said to be the largest covered market in the world. I’m not a shopper, but the Grand Bazaar (like the none-too-distant Spice Market) takes one back to the late-medieval or early-modern world, when bicontinental Istanbul was a focus of merchant trade routes linking not only Europe and Asia but Africa.

And then, finally, our group attended a whirling dervish ceremony at the HodjaPasha Culture Center. Although many no doubt see the dervishes as a quaint tourist attraction, they are far, far more than that. (Tonight’s ceremony wasn’t a “performance,” as is sometimes seen on cruise boats along the Nile. It was a genuine worship service, shortened for a tourist crowd. An odd comination, I know, but it worked.) The dervishes represent the Mevlevi Sufi order, which traces its genealogy back to the great thirteenth-century Persian mystical poet Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Rūmī, who spent much of his life in Konya, the ancient Iconium, and is buried there. Their spinning dance, in imitation of the movement of the celestial spheres, is designed to foster a separation of consciousness from the mundane world and a union with the divine.

In some respects, though not all, Rūmī is a very congenial thinker from a Latter-day Saint perspective. In the opening lines of his principal work, the Masnavi, for instance, he uses the reed flute as a metaphor for the human soul. It makes such a plaintive sound, he says, because it is in exile from the reed bed by the river, which is its true home. The lament of the reed flute symbolizes the soul’s sorrow at its separation or exile from God. We, too, are cut off from our source, from our original home, and are seeking reunion. Elsewhere he says

From the reed flute, the Master Artisan cut a flute with nine holes, and named it ‘Adam.’ O reed flute, you have been wailing with these lips.

Suggestions of an antemortal existence occur at more than a few places in Rūmī’s writings. And he even hints at what seems like a notion of human deification:

I died as a mineral and became a plant.

I died as plant and rose to animal.

I died as animal and I was Man.

Why should I fear? When was I less by dying?

Yet once more I shall die as Man, to soar

With angels bless’d; but even from angelhood

I must pass on: all except God doth perish.

When I have sacrificed my angel-soul,

I shall become what no mind e’er conceived.

Oh, let me not exist! For Non-existence

Proclaims in organ tones,

To Him we shall return.

There’s so much that needs to be said, so many stories that need to be told, about this absolutely wonderful place. But your patience is finite, and jet lag is unforgiving.

Posted from Istanbul, Türkiye