I would like to say a word about the Interpreter Foundation’s Not by Bread Alone film project, for which a website has now gone up that includes a preview video.

Quite predictably, I’ve been accused by one of the Usual Suspects of profiteering off of the backs of impoverished Congolese Latter-day Saints (and, it seems, of using my ill-gotten gains in order to finance my trip down here to Cedar City, where I’m selfishly immersing myself in Shakespearean and other plays to which my African victims will almost certainly never have access).

First of all, there will be no profit from Not by Bread Alone. We have no plans to monetize the videos. They won’t be shown in theaters. They will, as currently planned, be made available online at no charge. So, even if the relevant contracts and documents guaranteed me and my co-conspirators 100% of the profits, our payment would still be zero, for the simple and sufficient reason that there will be no profits. As things actually are, though, the contracts and documents make no provision for any percentage of the royalties to come to us. We didn’t bother to include such language because we foresee no royalties. Those who choose to support this film effort are told right upfront that they are donors, not investors. They will see no monetary return.

I don’t know how I can possibly be any clearer about this.

Moreover, the project is Afrocentric. What do I mean by this? As I understand it — I’m only peripherally involved in Not by Bread Alone; others are the principal managers and creators of it — two versions of the videos will be produced, one in French and one in English, and the first and primary audience for the videos will be Latter-day Saints in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which is a Francophone nation. We hope to have the video series completed and ready by the time of the dedication of the Lubumbashi Democratic Republic of the Congo Temple, for which ground was broken on 20 August 2022.

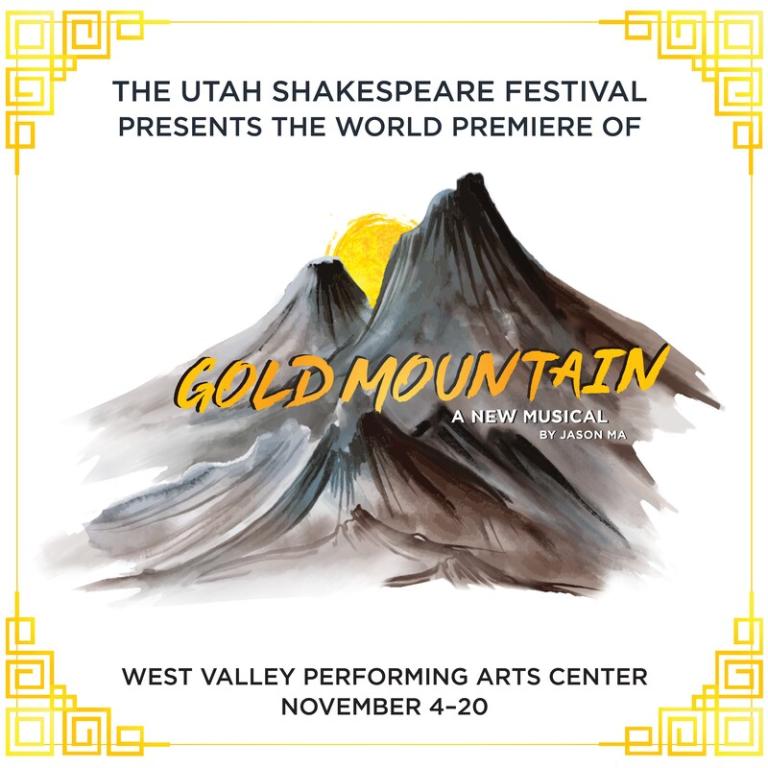

As for my selfish revels here in Cedar City, we are, as I write, not quite half-way through our plays for the year. There are seven of them. We had thought of perhaps catching an eighth play —Beautiful: The Carole King Musical, at Tuacahn — but a family obligation settled that question for us in the negative.

On Monday night, we saw Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It pains me to say this, but I’ll be honest and report that, roughly midway through the play, it occurred to me that this didn’t seem to be the quality of professional performance to which I’d grown accustomed over something like thirty-five years of attendance at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. And that worried me, both for this particular season and for the Festival more generally. It seemed, and I can’t quite put my finger on why, that I was watching a very good college production. Partly, I suppose, it’s because the play is a silly one. Especially at the end, where Bottom the Weaver (Topher Embrey) did a good job with his band of merry rustics in the play-within-a-play about Pyramus and Thisbe. The real stand-outs for both me and my theater-major wife were Theseus (Oberon) and Helena, who were superbly played by, respectively, Corey Jones and Kayland Jordan.

Yesterday afternoon, we saw The Play That Goes Wrong. I don’t think that anybody would confuse it with Hamlet or King Lear. It’s a farce, really quite funny, and without a single idea in it. As my serious theater-going friend here in Cedar City has put it, The Play That Goes Wrong makes Clue look like something by Ibsen. The audience thoroughly enjoyed it. And I’m not embarrassed to say that we did, too. The acting was quite good, so the worries that I experienced during A Midsummer Night’s Dream were largely allayed.

Last night, we saw Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun. I read it in high school, but had really not thought much about it since then, so seeing it was a bit of a revelation to me. Frankly, I had pretty much forgotten it, except that it’s a play by a black woman about a black family and that it takes its title from “Harlem,” a somewhat jarring poem by Langston Hughes:

What happens to a dream deferred?Does it dry uplike a raisin in the sun?Or fester like a sore—And then run?Does it stink like rotten meat?Or crust and sugar over—like a syrupy sweet?Maybe it just sagslike a heavy load.Or does it explode?

I found myself thinking, as I sometimes do, of Brigham Young. I suspect that his tastes in theater may have been more overtly didactic than mine are, and we definitely disagree on his distaste for tragedies, but I’m certainly grateful that he gave such strong support to drama from the very earliest days of Latter-day Saint settlement in Utah. (So, too, is my wife, the theater major.)

“If I were placed on a cannibal island and given a task of civilizing its people,” Brigham is said to have remarked, “I should straightway build a theatre.”

And, very plainly, history and his actions bear him out on that claim. Soon after they arrived in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, the Latter-day Saints erected a temporary shelter made from tree boughs on a frame structure that came to be called “The Bowery.” It stood on the southeast corner of what we now know as Temple Square. The forerunner of the Tabernacle, it was used for religious services — but also for concerts, plays, and dances.

In 1853, not much more than five years after the arrival of the Mormon pioneers in the valley, Salt Lake City’s Social Hall was formally dedicated. The non-LDS lawyer and federal territorial official Benjamin G. Ferris (1802-1891), a native of New York who was no friend to the Church, compared the theatrical performances held there favorably to dramatic presentations along the eastern seaboard.

Thereafter, in 1862, Brigham Young dedicated the Salt Lake Theatre, which was one of the finest theater buildings of its time anywhere in the United States. As he said,

Upon the stage of a theater can be represented in character, evil and its consequences, good and its happy results and rewards; the weakness and the follies of man, the magnanimity of virtue and the greatness of truth. The stage can be made to aid the pulpit in impressing upon the minds of a community an enlightened sense of a virtuous life, also a proper horror of the enormity of sin and a just dread of its consequences. The path of sin with its thorns and pitfalls, its gins and snares can be revealed, and how to shun it (Discourses of Brigham Young, 243).

That’s certainly the case with A Raisin in the Sun, even though it’s not expressly didactic or preachy. We were an overwhelmingly White audience, too — if not entirely so — and it was good for all of us, I think, to try to see the world through the eyes of a struggling Black family in the America of the fifties. This is one of the best things that good fiction can do: It allows us to expand our world of experience.

Posted from Cedar City, Utah