Our focus today was on the city of Gloucester, and most particular on the city’s cathedral. When I think of Gloucester, I’m afraid that the very first thing that occurs to me is Richard III, who reigned from 1483 until his death — the last English king to die in combat and the last of the Plantagenet monarchs — at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. Prior to his brief tenure as king of England, Richard was duke of Gloucester.

“A horse! A horse!” the beleaguered Richard cries shortly before his death in Shakespeare’s Richard III. “My kingdom for a horse!” And it’s Shakespeare’s Richard — one of the greatest and most cunning villains in all of literature — of whom I particularly think, although some are now arguing that Shakespeare’s portrayal of the king is wildly unjust and the product and embodiment of Tudor propaganda. (The Tudors were the family who displaced the Plantagenets and who overthrew and killed Richard.) One of the most spectacular pieces of acting that I’ve ever seen was Gary Armagnac’s depiction of Richard III at the 1994 Utah Shakespeare Festival. For sheer brilliant evil, I’ve never seen the like (although some of my critics would happily give me the edge in goofball evil, if not in brilliance). It is etched unforgettably in my memory.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

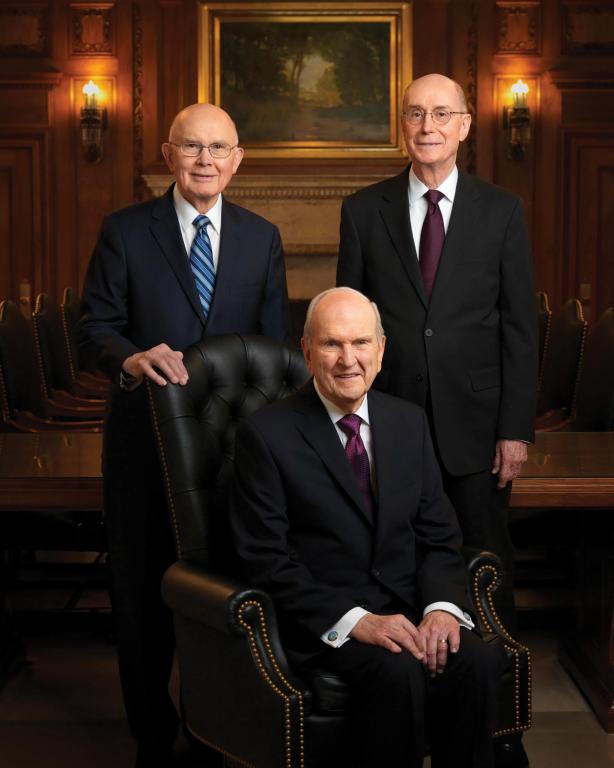

In any case, Richard Plantagenet is nowhere to be found in Gloucester Cathedral. Instead, the cathedral is the site of the tomb of Osric, the Anglo-Saxon King of the Hwicce, who founded what would eventually become the cathedral in about AD 679.

The tomb of Robert II of Normandy (ca. AD 1051-1134), or Robert Curthose, the eldest son of William the Conqueror, is also found in the cathedral. Robert was, by reputation, a heroic warrior. But he was passed over by his father for the rule of England, and probably for good reason. Somewhere in the cathedral literature today I saw a reference to him as “the king we never had” and, elsewhere, as “born to be king.”

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

In October 1216 Gloucester Cathedral was the venue for the coronation of Henry III, after the death of his father, the notorious King John, who has a bit of a public image problem and who could use some reputation management. John has his own play among Shakespeare’s historical dramas, but he is probably most famous for his enforced signing of the Magna Carta, on which he later tried to renege. He has been portrayed in film by Claude Rains (opposite Errol Flynn’s title role and Basil Rathbone’s Sir Guy of Gisbourne in the 1938 Adventures of Robin Hood, which has a special and cherished place in my unwritten autobiography) as well as by a cowardly thumb-sucking lion (voiced by Sir Peter Ustinov in the 1973 Disney Robin Hood). In The Lion in Winter, a very memorable 1968 film, John, who is the son of Henry II (Peter O’Toole) and Eleanor of Aquitaine (Katharine Hepburn) and the younger brother of Richard the Lion Heart (Sir Anthony Hopkins in his first significant film role), is portrayed as an effete weakling, but also as a dishonorable schemer.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

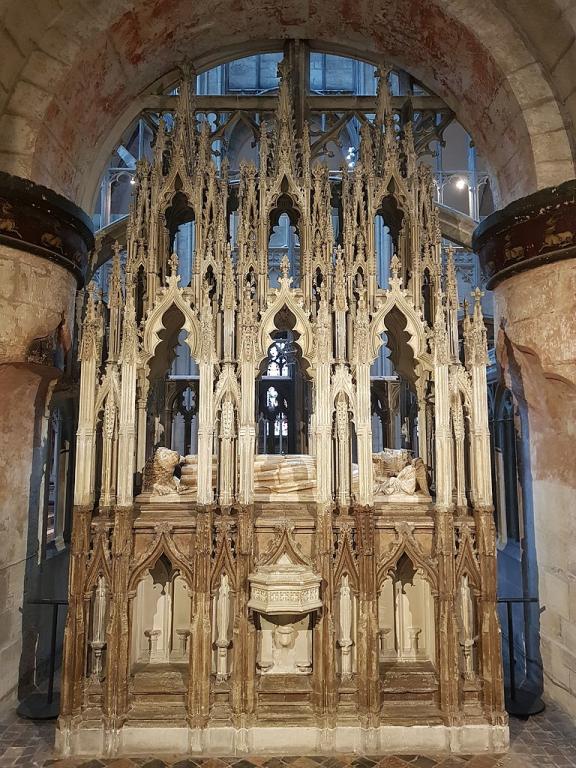

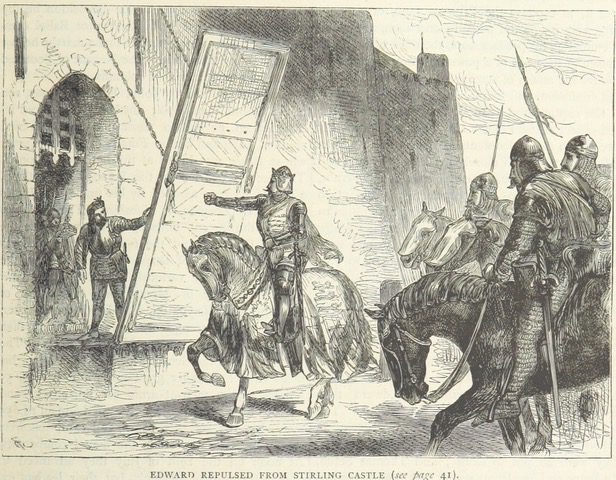

Perhaps the cathedral’s chief claim to specific fame — apart, that is, from its repeated use in the Harry Potter films (which isn’t altogether uncommon in the places we’ve visited during this trip) — is that it is the burial place of Edward II, the seventh Plantagenet king of England (who reigned, rather poorly, from 1307 to 1327 and who died under mysterious circumstances while effectively under house arrest in nearby Berkeley Castle). We had already spent some time with Edward II up in Scotland, when our group visited the site of the 23-24 June 1314 Battle of Banockburn, where the forces of Robert the Bruce, King of Scots, inflicted a decisive defeat upon Edward’s vastly larger army — some sources give figures of 27,000 English to 6,000 Scots — during the First War of Scottish Independence.

That was perhaps an omen of things to come for Edward II, as was the refusal of the lord of Stirling Castle — a place that we visited on the first day of our group tour — to grant him asylum following the battle.

There was actually a petition, centuries ago, seeking canonization for Edward II, probably on the basis of the fact that he was an anointed king and that his possible murder thus represented martyrdom. The Vatican apparently never acknowledged or responded to the petition. Which was probably lucky for Rome, since there is at least a fifty-fifty chance that Edward’s sexual practices were, umm, quite catholic. Which is to say that they may not have been Catholic. But this may be mere rumor, the result of propaganda designed to justify his having been deposed from the throne, and it may perhaps not be true at all. (The simple fact that a source may be old, or contemporary, doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s not biased or partisan or that it’s accurate. Historiography requires wisdom and judgment and, even so, it’s an inexact “science.”)

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

The Age of Chivalry has much to commend it. Unfortunately, it’s largely myth, and it was as corrupted by human wickedness as every other age has been. Perhaps, though, we can learn some virtues from the romanticized, purified accounts of it that survive in literary texts from the medieval period through the Victorians and beyond. I still love them.

Posted from Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England