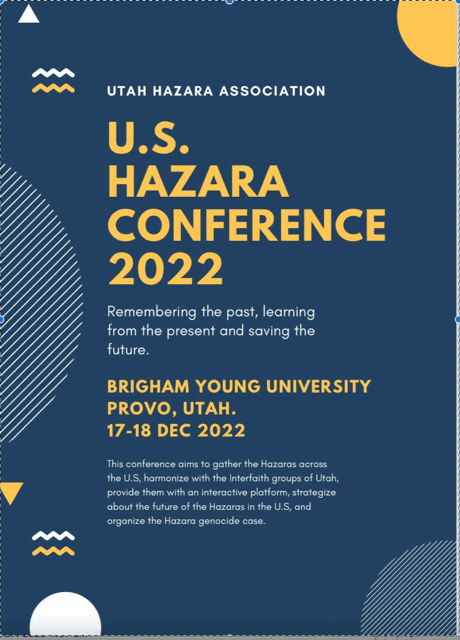

I spoke today at the U.S. Hazara Conference 2022, which was held in Provo, at the BYU Conference Center.

The program describes it as “the first ever Hazara conference.” “The conference aims to gather the Hazaras across the U.S., harmonize with the interfaith groups of Utah, provide them with an interactive platform, strategize about the future of the Hazaras in the U.S., and organize the Hazara genocide case.”

The Hazaras (هزاره) are a persecuted ethnic group that is native to a region in central Afghanistan known as Hazaristan or Hazarajat but who also live not only throughout Afghanistan but in Pakistan and in Iran. Predominantly if not entirely Shi‘i Muslims, they speak a dialect of Persian known as Hazaragi that is very similar to the dialect called Dari.

The topic that I was asked to address was “The Power of Prayer,” and specifically (curiously enough) to do it from a Latter-day Saint perspective. I tried to take an ecumenical approach to the topic, citing not only Latter-day Saint material but, even more, the Bible, as well as the Qur’an. There were excellent but challenging questions afterward. This is a people who have really suffered. It was humbling to be asked to speak to them.

***

I recently read Patrick Brissey, “Near-Death Experiencers’ Beliefs and Aftereffects: Problems for the Fischer and Mitchell-Yellin Naturalist Explanation,” Journal of Near-Death Studies (JNDS) lately. Here is the article abstract:

Among the phenomena of near-death experiences (NDEs) are what are known as aftereffects whereby, over time, experiencers undergo substantial, long-term life changes, becoming less fearful of death, more moral and spiritual, and more convinced that life has meaning and that an afterlife exists. Some supernaturalists attribute these changes to the experience being real. John Martin Fischer and Benjamin Mitchell-Yellin, on the other hand, have asserted a naturalist thesis involving a metaphorical interpretation of NDE narratives that preserves their significance but eliminates the supernaturalist causal explanation. I argue that Fischer and Mitchell-Yellin’s psychological thesis fails as an explanation of NDEs.

Patrick Brissey, Ph.D., is an instructor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of South Carolina who specializes in modern philosophy (especially that of Rene Descartes), the philosophy of religion, the history of philosophy, applied ethics, and logic.

***

I published this article in the Deseret News for Christmas 2015:

As I write, I’ve just returned from a funeral. Snow covers the ground; the trees are barren, seemingly dead. It’s the season described by Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73,

“When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

“Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

“Bare ruin’d choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.”

It’s a terrible time for a funeral, and the holidays are a terrible time to associate with the death of a loved one. And yet, in some ways, it’s the best possible time. For Christmas reminds us of the One who put an end to death.

Before his advent, death was a grim, hopeless inevitability. In the eleventh book of Homer’s “Odyssey,” for example, the hero Odysseus describes his perilous journey to the underworld, to Hades, where he converses with the spirits of the dead. He entices them with the blood of a sacrificed animal, something earthly and physical that they crave. Among those he meets is the great warrior Achilles, an old friend. Odysseus praises Achilles for his past glory and great deeds, but Achilles responds that earthly status means nothing to him now: “I’d rather serve as another man’s laborer,” he says bitterly, “as a poor landless peasant, and be alive on Earth, than be lord of all the lifeless dead.”

The dead, for the ancient Greeks, did live on, but only as “shades,” dwelling in literally Stygian darkness. (The term “Stygian” derives from the River Styx, which formed the boundary, in their conception, between the Underworld and the land of the living.)

Even the Hebrews often saw little if anything hopeful after death. Their appeals to God were continually for this-worldly salvation. “For the grave cannot praise thee, death can not celebrate thee: they that go down into the pit cannot hope for thy truth” (Isaiah 38:18) “For in death there is no remembrance of thee: in the grave who shall give thee thanks?” (Psalm 6:5) “Wilt thou shew wonders to the dead? shall the dead arise and praise thee? Shall thy lovingkindness be declared in the grave? Or thy faithfulness in destruction?

“Shall thy wonders be known in the dark? and thy righteousness in the land of forgetfulness?” (Psalm 88:10-12)

Joseph F. Smith, too, who saw the spirit world in a marvelous October 1918 vision, explained that, prior to Christ’s arrival there, “the dead had looked upon the long absence of their spirits from their bodies as a bondage” (Doctrine and Covenants 138:50).

And, for many today, the prospects are even bleaker. To them, only nothingness awaits us after death. The dead have ceased to exist. And all of us will soon follow them. Bertrand Russell, the most articulate and visible atheist of the twentieth century, strikingly expressed this viewpoint in his 1903 essay “The Free Man’s Worship”:

“That Man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins — all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand. Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built.”

For Christians, however, the advent of Christ marked the beginning of the end of death’s dominion. Of all good news, this is the best news possible: Because of God’s Word, death doesn’t get the last word. Because he lived, we will live.

Easter couldn’t have happened without Christmas. On our own, we could never have overcome death. God himself needed to come among us, to become one of us, to burst through the prison gates of death as the first of our kind, before the reign of sin and mortality could end. And he did it. (See Clayton Christensen’s eloquent words at http://www.mormoninterpreter.com/he-did-it-a-christmas-message/#comments.) As it turns out, God does show wonders and declare his lovingkindness to the dead.