For the record: I wasn’t involved in THIS episode, either.

For one reason or another, I still haven’t managed to watch the Netflix documentary series Murder Among the Mormons. Somehow, when I’ve begun to wind down late at night in recent weeks, I just haven’t been in the mood for it. I know that I need to watch the thing, but I always decide that I’ll watch it tomorrow night. Mañana. My wife and I like to relax before bedtime with BBC versions of classic novels or British detective shows, or with good books. Right now, for instance, I’m reading (and enjoying) Mark Twain’s relatively little-known 1896 novel — his last completed novel, and his own personal favorite — Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc.

I hadn’t seriously thought about Mark Hofmann, his forgeries, and his crimes for many years, but I’ve commented on them a few times in the past couple of weeks.

Yesterday, I think, I responded to a comment to one of these blog entries by noting of Mr. Hofmann’s so-called “Salamander Letter” that “I can’t prove it, but I doubted it from the start.”

Elsewhere, it’s been suggested by one of the usual suspects that I’m lying on that point. Surely, for example, I should be able to demonstrate that I really had such early doubts (via an article in some academic journal, for example). And surely I shared my insights with the leadership of the Church and/or with local Utah law enforcement and the FBI. So there should be solid proof of my “boast” on this score, right? Otherwise, as on every other occasion when my lips are moving or my fingers typing or my hand writing, I’m lying.

And here’s the really damning proof:

F.A.R.M.S. UPDATE

(c) June 1985

Moses, Moroni, and the Salamander

Martin Harris’ letter of 23 October 1830 to Wm. W. Phelps (published in Church News, 28 April 1985) has dismayed some people. Harris talks of a “white salamander” which was “transfigured” into “the spirit” otherwise known to us as the Angel Moroni. We may never know whether this description was an embellishment on the part of Harris, or an allegory employed by Joseph Smith, or whether Moroni somehow chose to appear to Joseph out of, or in the form of, a salamander. But since Phelps joined the Church after reading Harris’ letter, he must not have found the allusion to a salamander very disconcerting. In fact, as new research is showing, the salamander has been thought for millennia to have supernatural and extraordinary powers. Consider the following:

1. Well into the 19th century, it was commonly believed that salamanders “lived in or were able to endure, fire.” Numerous references to this wide-spread belief are listed in the Oxford English Dictionary under “salamander.” Long before, even Aristotle — of all people — reported: “The salamander shows that certain animals are naturally proof against fire, for it is said to extinguish a flame by passing through it.” Historia Animalium V.19, 552b.

2. Indeed, salamanders were thought to be “generated in fire.” The great Rabbi Akiba held to this view, in Hullin 127a. Other rabbis, including the noted Rashi, debated whether the fire had to be heated for seven days, seven years or seventy years to produce a salamander that would appear walking and flying in the midst of the fire. (Should we compare Dan. 3:19ff.?)

3. Accordingly, salamanders were often associated with spirits. In Germany, salamanders were thought to be “Wetter-propheten” (weather-prophets), and “Hausgeister” (house-protector spirits). German churchdoor locks and bolts, as well as ovens and fireplaces, had salamander insignia on them. Handwoerterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens (Berlin, 1934), 6:458. In the Middle Ages, the salamander denoted “a being possessing the shape of a man whose element was the fire, or who at least could live in that element.” Chambers’s Encycl. (1875), 8:436. Earth, air, fire and water, each had a spirit — for fire, it was the salamander.

4. Moreover, salamanders were associated with the voice of God and with the Holy Ghost! From Midrash Ex. Rabbah XV.28 on Exodus 12, we find that the rabbis of the 9th Century A.D. and before believed that “God had to show Moses on Mt. Sinai was the salamander: “He stirred up the fire and showed him the salamander, for it [Ps. 29:7] says: The voice of the Lord heweth out flames of fire.” In 1841, the baptistry of Winchester Cathedral in England bore the figure of a salamander, alluding to the words, “He shall baptize you with the Holy Ghost, and with fire.” G. A. Poole, Churches: Their Struct. Arrang. & Decor. 9,2.

5. Since the salamander was said to endure fire, it was thought to protect others against burning, including hell-fire. The rabbis remarked that hell would not harm scribes, since they were “all fire, like the Torah; and if flames cannot hurt one who is anointed with salamander blood, still less can they injure the scribes.” Jewish Encycl. (1905) 10:646, citing the Talmud Hagiga 27a. A similar popular belief seems to stand behind Austrian lore relating the salamander to the atoning suffering of Christ. The Zohar (ii. 211b) mentions protective garments of salamander skin.

6. Not far removed from these ideas about salamanders are ideas depicted by the biblical phrase “fiery flying serpents” Were these “salamanders”? A brass model of this reptile symbolized Jesus himself, who commanded Moses to put it up on a pole, so the people who had been bitten could look to it and live (Num. 21:6-9; 1 Ne. 17:41; cf. Is. 14:29; 30:6; 2 Ne. 25:20). The Hebrew word here for “fiery” is saraf. This strongly suggests a further connection with the six-winged seraphim (Is. 6:2-6) and the nearly identical cherubin (Ezek. 1 & 10; Rev. 4:6-8). Cf. Egyptian srf (“griffon”). Were their six wings and abstraction from the six, red, wing-like, external gills of salamanders?

7. Eternal life and resurrection were also symbolized by the salamander. The Arabic word for both the salamander and the phoenix, which could die and rise again out of its own ashes, was samandal. See Al-Jahiz, Kitab al-Hayawan (9th c.) 5:309-10 (Harun edition); S. Nasser, Intro. to Islamic Cosmology, 2d ed., 273 n. 29.

8. People too were sometimes called salamanders. Shakespeare calls a fiery-red face a “salamander.” Henry IV, III, iii, 58. Likewise called were soldiers who courageously exposed themselves to fire in battle. Salamanders appear in medieval and renaissance coats of arms, including that of Francis I, King of France. Thomas Brooks in 1670 wrote, “God’s people are true salamanders, the live best in the fire of afflictions.” Works 6:441.

9. Not all salamanders were good, however. The poisonous ones are “spectacularly colored” with bright spots on a dark background. Encycl. Brit. (15th ed.), Macrop. 18:1087. They were linked with evil spirits. But the non-poisonous good ones were white or grey-brown.

Obviously, much has changed culturally since 1830. Some of us may wince at the suggestion that an angel of God should be associated with, or described as, a salamander. But to people then, no image or description would better fit the appearance of a brilliant white spiritual being, once a valiant soldier, now dwelling in a blazing pillar of light, shockingly pure and glorious, speaking with the voice of God while flying though the midst of Heaven, then the salamander! Moroni should be flattered. (JS-H 1:30-32; History of the Church 4:536).

Still, it was predictable that people would not understand this. The Lord apparently knew this would happen. In 1829, God commanded Harris not to try to describe things which he had not personally witnessed: “And I the Lord command him, my servant Martin Harris, that he shall say no more unto them concerning these things, except he shall say: I have seen them, and they have been shown unto me by the power of God; and these are the words which he shall say.” D&C 5:26. Harris seems to have overstepped his commission here when he wrote to Phelps in 1830.

Further research is still underway. Glenn Clark’s recent “Pillars of My Faith” presentation at the Sunstone Theological Symposium (May 18, 1985) covers several of these points and will soon appear in Sunstone. In the end, this research may lead to a less “modern” view of many symbolically meaningful religious events: a burning bush; a talking ass; a flaming sword; a tempting snake; the Lord with seven horns and seven eyes; a descending dove; and a salamander angel.

(FAIR USE COPYING NOTICE: These pages may be reproduced and used, without alteration, addition or deletion, for any nonpecuniary or non-publishing purpose, without permission.)

This 1985 document was issued, one critic observes, under my leadership of the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), the forerunner of the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship. That proves beyond question that, when I boast today that I always doubted the authenticity of the “Salamander Letter,” I’m not telling the truth.

Well.

When Mark Hofmann burst upon the world of Latter-day Saint historiography with his forged “Anthon Transcript” in 1980, I was living with my wife in Cairo, Egypt. And we were still living in Egypt in 1981, when he “found” evidence of a blessing in which Joseph Smith supposedly promised the presidency of the Church to his son Joseph III.

It will be difficult for some to imagine such a thing, but this was a time without the internet. In Cairo, in fact, it was a time essentially without telephone connections (even across the city, to saying nothing of international calls). We occasionally heard something about Mr. Hofmann’s document “discoveries” — but very little, sketchily and after long delays.

My wife and I returned from Egypt in the summer of 1982. I was in residence for a doctorate at the University of California at Los Angeles from mid-1982 until roughly August 1985, when, really just beginning to work on my dissertation, I joined the faculty at Brigham Young University. When I wasn’t actually teaching, I was busy writing a long and very technical dissertation and inventing my new classes.

The “Salamander Letter” appeared in 1984. I was still a graduate student outside of Utah at the time. I was on the periphery of the Latter-day Saint academic community, and I was focused very much on Arabic and Islamic studies. More and more, in fact, on Isma‘ili Shi‘i Neoplatonism. I wasn’t exactly a close advisor to the Brethren. Why is there no evidence in any academic journal of my doubts about the “Salamander Letter”? I hadn’t yet published in my own field, let alone on Mark Hofmann’s document “finds.”

I chatted with Latter-day Saint friends about the case, but I doubt that our conversations were recorded and archived. I thought the FARMS material on salamanders intriguing and plausible. But I also had begun to worry about Hofmann’s string of spectacular document finds. It just seemed too much. And, for me, the salamander simply didn’t quite fit. Why had nobody else written like this?

When FARMS published its little response to the “Salamander Letter,” I was just finishing up my coursework at UCLA and preparing to move up to Utah to teach at BYU. I wasn’t at BYU yet. I wasn’t the chairman of FARMS. I wasn’t even affiliated with FARMS.

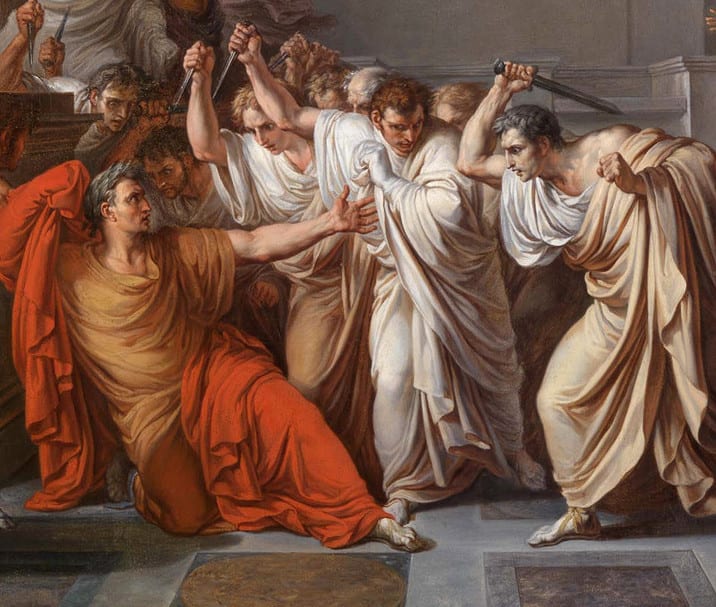

Hofmann committed his murders in October 1985. I had been in Utah for roughly two months by then, as a brand-new faculty member. Some of us had hallway conversations about the case. So far as I know, none of them were recorded. None have been archived.

Mark Hofmann was arrested in January 1986. He pled guilty to murder in January 1987.

Jack Welch asked me to create the Review of Books on the Book of Mormon, which eventually became the FARMS Review, in 1988. The first issue appeared in 1989. That was my first official involvement with the organization, and, at the time, that was the totality of my involvement.

I was invited to join the Board of Directors of FARMS in September of 1991, and I served as chairman of the Board from July 1997 through June 2001. Which should suggest to careful readers that I was not in charge of the organization in June 1985, when the document above appeared.

And, just to head some of my critics off at the pass: I was not on the grassy knoll in Dallas on 22 November 1963 and anyway, I was only ten years old at the time — which doesn’t make my involvement in the Kennedy assassination altogether impossible, but it does make it at least a bit less believable. Also, I neither knew nor had any contact with Jimmy Hoffa. Moreover, I have not the faintest idea where Elvis might be. And I sought sanctuary in neither Brazil nor Argentina at the end of the Second World War.

Incidentally. the argument made by the FARMS document above is actually not unreasonable. It was written at a time when various experts had “authenticated” the “Salamander Letter,” and, accordingly, responsible and faithful Latter-day Saint scholars tried to take it into account and to put it into a context that was consistent with Latter-day Saint faith. And what they found about the place of salamanders in hermetic lore was really quite interesting. They weren’t making it up — probably because Mark Hofmann had made a cunning choice in his fictional salamander. He didn’t choose it at random. The FARMS defense proved unnecessary, but it was not unsound. I just had absolutely nothing to do with it.