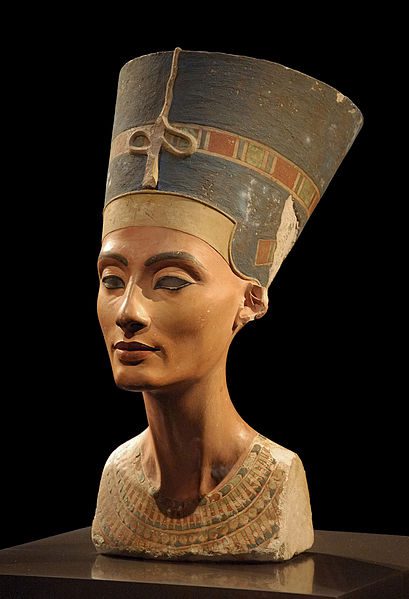

Neues Museum, Berlin. Photo by Philip Pikart

In person, she’s even more stunningly beautiful than the photographs of the bust can convey. My wife thinks she’s a double for Audrey Hepburn. She’s been dead for approximately 3351 years.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

I decided, this morning, to watch again the Interpreter Foundation’s first somewhat experimental venture into filmmaking, Robert Cundick: A Sacred Service of Music. I hadn’t seen it for a while.

It’s just short of twenty-five minutes in length, and I was pleased to find that I still like it very much and that I still think it well done. (Incidentally, the same trio who were the principal figures in making it — Mark Goodman, James Jordan, and Russell Richins — are the same three who are principally involved in our Witnesses film project.) Originally, making the Cundick film was my wife’s idea.

On the other hand, and quite in contrast, I was struck by how inadequate the film is.

What do I mean by calling it “inadequate”?

I knew Bob Cundick. My wife and I became acquainted with Bob and his wife, Cholly, during the first half of 1993, when we were all four serving at BYU’s Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies. He was the Center’s organist and, together, they were in charge of its hosting and public outreach. (If I recall correctly, he also served during his stay in Israel as the organist of the Lutheran Church of the Redeemer, which is located right in the heart of the Old City, very near to the ancient Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The Lutherans were incredibly lucky to have him.)

I mean to say that no film — whether twenty-five minutes long or four hours or four days — can do justice to a good and productive life, just as no biography can ever fully sum up a life well-lived.

There is, so far as we humans are aware, nothing richer in the universe than personality. There is nothing so endlessly fascinating. It’s not just that “The brain is the last and grandest biological frontier, the most complex thing we have yet discovered in our universe. It contains hundreds of billions of cells interlinked through trillions of connections. The brain boggles the mind.” (See here.). It’s not merely that the human brain is far more complicated and difficult to understand than a rock floating in space or a gaseous and luminous spheroid of plasma held together by its own gravity that we term a star or even a galactic assemblage of such objects.

No, I’m not talking here about neuroscience or cranial anatomy. I’m talking, very specifically, about personality. There is nothing more inexhaustibly interesting, complex, and rich. Nothing.

So the loss of any person is, to me, incalculable. Every person is unique, irreplaceable. Like a snowflake, but infinitely more important and infinitely deeper.

Thus, the famous lines from Meditation XVII of John Donne’s 1623 Devotions upon Emergent Occasions have always resonated with me:

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

I’ve always been inclined to read obituaries. And each obituary that I read, whether for a friend or a person unknown to me, whether for a celebrity or a “private person,” leaves me with the acute sense that experiences and perspectives that are utterly unrepeatable, unparalleled, and beyond price have been lost.

It’s a peculiarity of mine, I’m sure, and it might surprise some who have detected no traces in me of the macabre or the morbid or the funereal or the gloomy — and they’re not misreading me in that regard — that I’ve always been acutely aware of the transience of human creations and even of natural phenomena. When I see beautiful flowers, I can’t help but think of the fact that they’ll soon fade. When I see geological formations, I know not only that they were created over time but that they are still being created — which means, inevitably, that they’re being destroyed. Tectonically speaking, the Pacific Plate upon which I was born has moved somewhere between seventeen and twenty-three feet to the northwest since I drew my first breath. Even the most beautiful architecture reminds me of foredoomed sand castles. When I’ve visited castles, palaces, and historical mansions, my thoughts have almost invariably turned to the brief time that their builders occupied them and how long those builders have now been gone. (Perhaps I’ve spent too much time studying and, in a sense, living in ancient and medieval times; I can’t avoid thinking of the fact that those who ruled over Old Kingdom Egypt and who have been gone for nearly five millennia were once every bit as vivid and alive as the youngest and healthiest of us today. Most of them — to say nothing of their courtiers and of the peasants below them — are completely forgotten.) In planning for retirement, I know that it will last only a short while, and that I have, at the best, far fewer years ahead of me than I’ve already lived.

I’m fairly gregarious and not notably lonesome, and I’m not especially well known for my grim solemnity, but another passage that has echoed in my mind for decades can be found in Jacob 7:26, where the aged prophet Jacob reflects on his life and comments that

the time passed away with us, and also our lives passed away like as it were unto us a dream, we being a lonesome and a solemn people.

(By the way, this doesn’t strike me as the kind of thing that a healthy, seemingly indestructible and immortal young person — say, Joseph Smith in his vigorous early twenties — would be likely to write. But it makes enormous sense to me now that I’m stumbling inescapably into advanced decrepitude, continuously astounded to be as old as I am, much older than my father was when I began to worry about his age. Where did the time go? Have I been sleepwalking? When older people commented to me about how short life is, I would smile and nod my assent without real comprehension. No longer.)

Surprisingly, I don’t think that I feel any particular or unusual fear of my own personal death, or that I ever have. But I’m offended by death. I’m offended by the fact that it’s taken many of my loved ones, many of my friends, many people that I have admired, and many that I dearly wish were here to help us out today.

I recall when we were driving, years ago, in a small funeral procession toward the cemetery for my father’s burial. Suddenly, and quite unexpectedly, it struck me as almost incredible that, as we passed, people were shopping and gassing up their cars and laughing and listening to music and enjoying the sunny southern California weather as if nothing had happened. But something monumental had happened. Were they really unaware of the cosmic obscenity that had just occurred? My father — the North Dakota farm boy, son of immigrant Scandinavian parents, veteran of the Great Depression and President Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps and General Patton’s Third Army and the liberation of the Nazi extermination camp at Mauthausen, builder of a successful business and of a not insignificant number of construction projects across booming post-war greater Los Angeles and beyond, a gentle and good-humored man who was held in affection by many, a father and grandfather and brother, late in life turned a Latter-day Saint, a hunter and angler and golfer and prankster and joker and genealogist and Scouter, and so many other wonderful things — was suddenly, unreachably, gone. Just gone.

Yet life went on uninterrupted, despite the enormity of what had just happened.

I thought of videos that I’ve seen of deer grazing in a meadow. A shot rings out, and one of them falls to the ground dead. They look up, startled. And then they go back to grazing, thoughtless and unconcerned.

We have no alternative, of course. In the words of the old Joni Mitchell song, “we’re captives on a carousel of time.” We can’t just say “Stop!” and expect it to stop.

I realize perfectly well, of course, that my indignation at death doesn’t make it unreal. Nor does it confirm as true my belief in a life beyond life, and even (as N. T. Wright would say) in a resurrected life beyond life beyond life. But I confess that it does make the indifference and apathy and thoughtless inattention of many toward the matter utterly incomprehensible to me.

***

Okay. I have to admit that the article above stunned me. Obviously, lucrative as college teaching is — to say nothing of the massive wealth (mostly in gold bullion deposited in secretive Swiss and Cayman Island bank vaults) that I’ve acquired by engaging in Latter-day Saint apologetics! — I went into the wrong field.

So I hereby announce Boot Me Inc., a Daniel C. (for “Coach”) Peterson Football Program Severance Company.

I will take over any college football program in the country, fail quickly and miserably, and accept severance pay never to exceed one or at most two million dollars. In other words, my payment expectations will be much lower than the going rate. Especially in a time of pandemic and low ticket sales, I think that my new business model should be extremely attractive to struggling college athletic departments.

***

And, speaking of football coaches, here’s a really nice portrait (with some bittersweet elements) of a Latter-day Saint who has succeeded in the National Football League:

“The rehabilitator in chief: How Andy Reid built a champion on second chances”

***

I have, as I’ve previously indicated, sworn off any and all public commentary on partisan political issues, and have done so at a time where I would like to comment publicly perhaps more than I have ever wanted to do so at any previous time of my life. Pity me.

But I did indicate that I reserved the right to comment publicly upon broadly political matters, specifically mentioning, as examples, questions of religious liberty and questions relating to the Middle East or the world of Islam.

Well, it’s time.

I’m no fan of the Islamic Republic of Iran, but I strongly endorse this OpEd in the Los Angeles Times by John W. Limbert and my friend Bahman Baktiari, who is the former director of the Middle East Center at the University of Utah:

“Lift US sanctions that block Iran from buying COVID vaccines”